The difference between innovators and entrepreneurs

Simply sign up to the Retail & Consumer industry myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

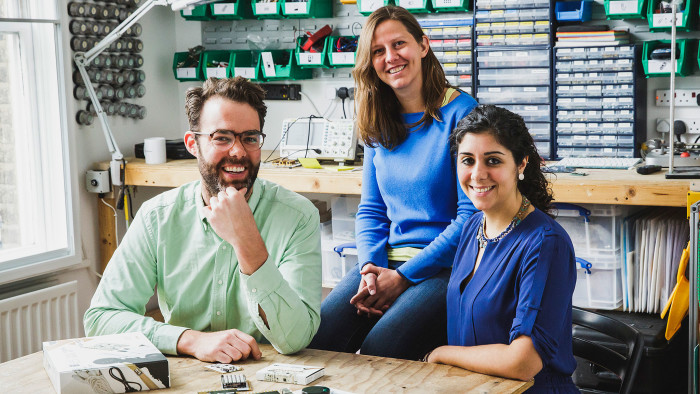

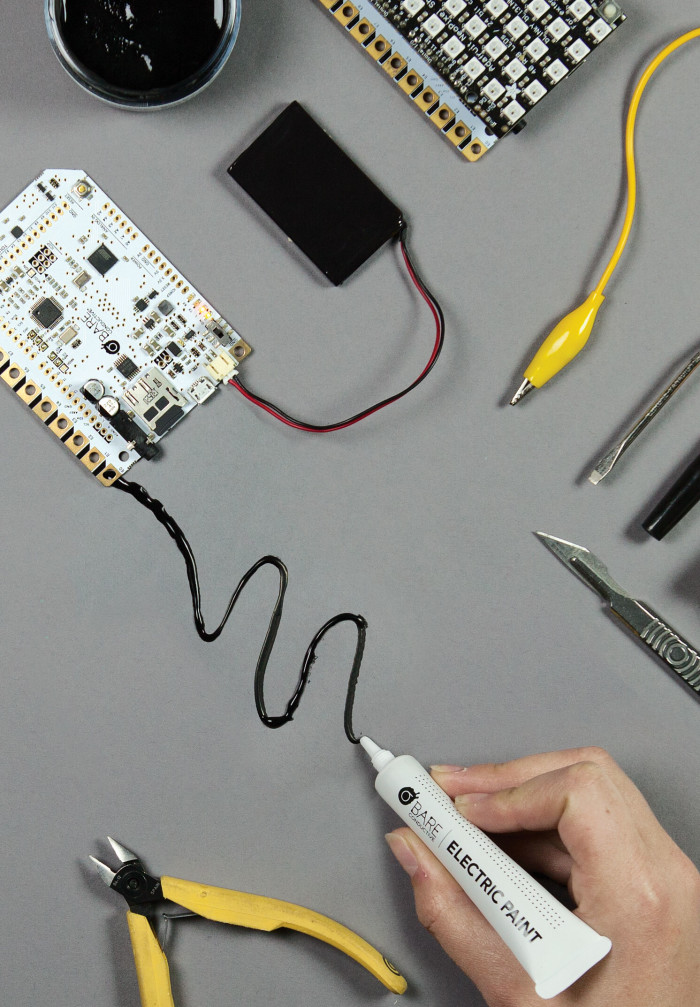

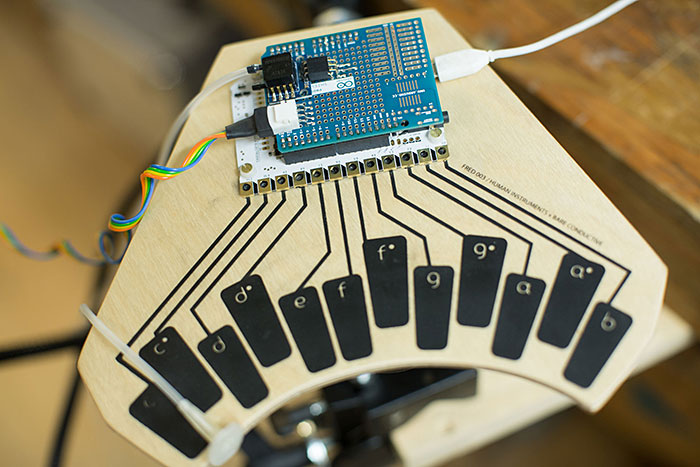

Matt Johnson was raised by entrepreneurs — his parents founded Denver-based landscape architecture practice Civitas — but he had no intention of creating a company himself. That was until, as part of his industrial design degree at London’s Royal College of Art, he invented conductive paint, with which he could create working electrical circuits on walls.

Now, Johnson is chief executive of Bare Conductive, a business formed around his product employing 10 people in a studio in Shoreditch, the east London tech start-up hub. The company has generated revenue of over £2.5m in six years of trading, selling its paint in kits through hobbyist websites and retail chains such as RadioShack in the US. Johnson is in discussions with several FTSE 100 companies about taking operations to a much larger scale.

Many inventors like Johnson try to turn their innovations into businesses, but few reach a large scale. More often it is companies led by entrepreneurs, rather than inventors, that change society with their products.

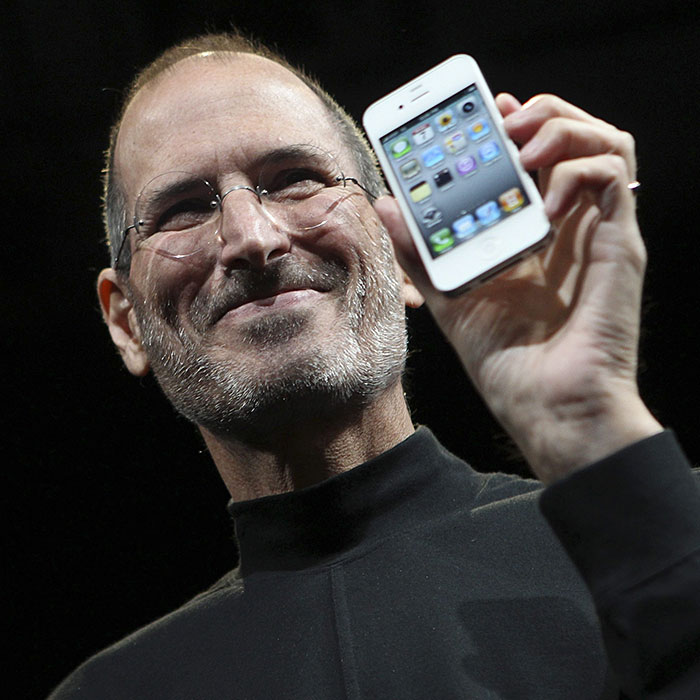

Steve Jobs did not invent the smartphone and Bill Gates did not create the personal computer operating system, but both built their companies into world leaders on the back of these innovations.

Julian Metcalfe and Sinclair Beecham, the founders of Pret A Manger, did what the Fourth Earl of Sandwich failed to capitalise on when he gave his name to the filled bread snack in the 18th century. In the 1980s, they bought a sandwich shop in Hampstead, north London, that was in liquidation and turned it into a global chain with almost 500 shops that sold £776m of snacks and beverages in its last financial year.

“I was lucky because I could follow the example of my parents,” Johnson says. He also relied on mentors to help him develop as an entrepreneur, and brought in other people to take on business functions that he did not have the skills to do.

Having moved from inventor to entrepreneur, Johnson says he has developed a respect for those whose skill is to create companies rather than make technological breakthroughs. “I now understand that creativity isn’t only the realm of those creating objects,” he says. “Creating a company, to me, that is total magic.”

The stumbling block for many inventors is moving from being a small-scale operation to a large business, says Simon Bond, innovation director at SETsquared, an incubator programme set up 15 years ago by five UK universities to turn academic breakthroughs into large companies.

Thousands of inventors approach SETsquared for support. The incubator identifies those that truly have an entrepreneurial bent by insisting that everyone goes on a two-day introduction course that outlines how someone takes an idea from the back of a napkin to a commercial venture.

For many the stumbling block is about control, such as not being able to decide how the innovation should be commercialised or having to share their ideas with a management team, says Bond.

Those who do stay with SETsquared are those who are able to share the vision, he notes, often finding a mentor during the introductory course who later becomes the company’s chief executive. He cites the example of SETsquared alumnus Symetrica, a security systems supplier. It was based on a discovery in gamma ray technology by David Ramsden during research at the University of Southampton.

Ramsden had come to SETsquared imagining that his discovery would be of most use detecting low-level radiation in satellites, but after meeting mentor Heddwyn Davies, later Symetrica’s chief executive, he was convinced that there was a business opportunity in the technology’s potential to detect dirty bombs at security checkpoints at ports, for example. The company, which has raised $4.7m to date from private equity, is now a supplier to homeland security operations in the US.

“Successful businesses are more than great ideas,” Bond says. “Expanding the business consistently in a way that engages more than a top tier of customers takes more than a single invention.”

Entrepreneur First is a London-based accelerator programme that helps technology graduates and those already working in tech start-ups to discover their inner founder. In the six years since it was launched it has enabled the creation of 150 companies, valued collectively at about $1bn.

None of these founders would describe themselves as inventors, even though most have an engineering background, notes Matt Clifford, Entrepreneur First’s chief executive.

“The invention itself is rarely the key to the whole thing at least with technology companies,” he says. “We look for people with a bigger vision, who can think in an unconstrained way, not limited by the original idea for their product.”

Comments