David Chipperfield’s daring new role at Driade

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

David Chipperfield is looking surprisingly diminutive today. Silver‑haired, dressed in black trousers, a black poloneck and thick black-framed glasses, he is surrounded by key Italian journalists and magazine editors, plus an entourage of chicly dressed staff, also clad in black, at this, his first press conference as artistic director of Italian design firm Driade.

We are crammed into the back of Driade’s new Milan showroom, an elegant white space designed by David Chipperfield Architects, and waiting to hear all about why, having saved Driade from financial difficulties in 2013, its CEO Stefano Core has now decided to appoint an architect, and a British architect at that, as its rescuer and its touchstone going forwards.

Chipperfield – speaking in English rather than Italian – is relatively reserved. But despite this, he has an air of quiet confidence and his audience are all ears. Although his work is relatively limited in the UK – buildings include Yorkshire’s Hepworth Wakefield gallery and Margate’s Turner Contemporary, plus a small number of residential projects, among them an upcoming tower development with homes and offices in Waterloo – in Europe over the past few years he has become a revered architect, projecting a thoughtful (but still bold), minimal and modern approach to structures that doesn’t provoke controversy for its own sake. He is not wedded to a particular style irrespective of a building’s surroundings. A close architect friend describes his work thus: “It is rigorous, well executed. It’s a very British London style. I saw the Neues Museum in Berlin a few years ago and it’s beautifully done.”

Indeed, it is in Berlin that Chipperfield’s reputation has reached its maximum approbation. David Chipperfield Architects has over the past few years been sleekly renovating Berlin’s “Museum Island”, including the aforementioned war-torn Neues Museum, and Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie. When Chipperfield started on the museum projects there were demonstrations against his selection, but, he says, he won the Germans over by being mindful of the history of their cities and how modern buildings need to sit comfortably within them (he kept all the original features of the Neues Museum). He recently described his architectural ethos as “accept[ing] that we are trapped by history, and that’s part of the richness of culture”. And continental Europeans love him for it.

Now, in the UK too, Chipperfield’s profile is finally in the ascendant. He won the 2011 RIBA Royal Gold Medal for Architecture, a 2010 knighthood for services to architecture in the UK and Germany, and his London office is redesigning part of Selfridges’ Duke Street façade and entry building.

So why, with a new office in Shanghai and in excess of 200 employees in Milan, Berlin and London working on a global portfolio (and when Chipperfield himself admits “I’m an architect and not a designer”), has he taken on an artistic directorship at an Italian interiors brand known for its elegantly experimental furniture and accessories designs – including moulded plastic armchairs like the Soft Egg (from £185) and Lord Yo (from £260) by Philippe Starck, and the body‑moulded (complete with pert “bottom”) Nemo chair (from £1,095) and city-square Piazze trays (from £615) by Fabio Novembre?

The answer, it turns out, is extremely personal. Chipperfield has for many years been a close friend of Enrico Astori, who founded Driade in 1968 with his wife Adelaide and sister Antonia. The decline of Driade, leading up to its sale in 2013, posits Chipperfield – now seated on one of the firm’s sofas after the press conference – was the result of difficult trading times coupled with difficult family circumstances (Astori’s ageing and the loss of key family members).

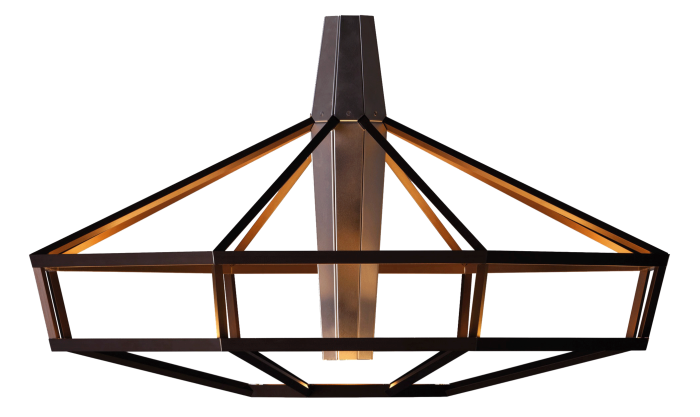

Driade’s current Italian parent company, ItalianCreationGroup, spent a year getting Driade back on track. The next step was to get a high-profile head. “Only someone of great professionalism could lead this company. But I also wanted someone who hadn’t headed up any other interior design brand,” says Core, who had been “kind of creative director myself” leading up to the 2014 launch of a number of very strong products, including a rust-coloured anodised aluminium “cage” chandelier (Lampsi, from £2,856) designed by Park Associati, a leather-wrapped dining chair (Rikka, from £1,560) by Maurizio Galante in differing shades of red and purple, and a fabulous raw-edged quartzite-topped dining table (Basalt, range from £3,264) by UK duo Fredrikson Stallard. However, he believed they required someone of Astori’s stature to provide a link between Driade’s huge heritage and the future. The choice of Chipperfield thoroughly met with the approval of Enrico Astori, who remains Driade’s honorary president. “We will never get him,” Core admits was his first feeling. But then Astori was persuaded to ask Chipperfield himself. “And when David’s initial reaction was to say how honoured he was to be asked… well, that’s when I thought we had a chance.”

The 20-year bond between Astori and Chipperfield is undoubtedly a close one. “Every time I came to Milan, Enrico put on dinners for me, made me feel extremely welcome,” says Chipperfield. “He and his family have always been incredibly generous, and we developed over time a true friendship.” Elisa Astori, Enrico’s daughter, who still works for the company, says he shares many of her father’s traits. “I was studying architecture when I first met him and I admired his work hugely. So knowing him personally was a great honour, but he is also very curious, likes cooking and having friends for dinner, and also, of course, has great charisma.”

However, Chipperfield didn’t say yes out of a feeling of obligation. “I wouldn’t have done it if we didn’t have an Italian office. Working here you see that it’s almost impossible to be an architect, but it’s a fantastic culture still for design. It makes me feel, ‘What can we contribute?’ Both architecture and design are cultural tasks, so it’s not completely different to everything we do. And I’m certainly not in it to waste my time.”

But this is not Chipperfield’s first foray into product design: he has a very simple, earthy line of dining ceramics with Alessi (Tonale, from £16) – influenced by Giorgio Morandi, his favourite 20th-century still-life artist – and also a friendly yet minimal folding dining chair (Piana, about £134) for the same company that takes something from the original utilitarian folding chair by Giancarlo Piretti. A reading lamp (Evelyn, £906, named after David’s wife), designed for the Shore Club hotel in Miami and made of aluminium with a coloured metal cone on the top, has been relaunched this year as a Driade product. In addition, not far from Driade, on the Via Monte Napoleone, is the Valentino fashion store – one of several global outlets David Chipperfield Architects has designed for the brand over the past few years. Among them is the New York flagship, which is all gorgeously luxurious textural stone and shiny brass accessories and lighting, including (and he is rather proud of this) the clothes hanging system in its entirety.

Chipperfield has been involved with Valentino for several years. “The experience of working with the brand has been incredibly enjoyable,” he admits. “They’re commercially very clear, commercially very powerful now, but when we started Valentino himself had just moved on and they didn’t know what to do. It was a difficult period, and we feel that six or seven years on we have their confidence. We have been part of rebuilding the company. They certainly don’t regard us as just the people who build their shops.”

Because of this, and because of his understanding of the history of Italian design of the past century – Giò Ponti and Franco Albini in particular are his design heroes, on the basis of their pluralism and their philosophical and intellectual approaches to design – Chipperfield felt he understood Driade and what he wanted to do with it. “When I was young we had two pairs of shoes and a couple of Aertex shirts and those were all the clothes you needed. Today my kids [he has four in their 20s and 30s] have all the clothes they want. Design has become a tool to stimulate what we might want. You want to have nice shoes and then some more nice shoes, and while there’s nothing wrong with wanting better objects and there’s nothing wrong with the desire for something that is beautiful, you could argue that design has become part of that conspiracy to satiate the consumer. I don’t think we should be producing so much stuff, and there’s a lot of rubbish around. I think we need to be more discriminating about what design is for.”

Chipperfield’s approach for Driade, which he feels follows in the spirit of Astori, is one of “open-mindedness, a pluralistic view. It’s not design as taste. Enrico was not afraid of making mistakes and being very experimental. The issues now are how to keep alive that spirit, that very pure quality he had, and understand this DNA while having commercial credibility. It could be easy to relaunch Driade with five new designers, but I don’t want to innovate just because the market expects me to. It’s more important to look at the archive and better understand the Driade spirit and learn how to apply this in a much more commercial and professional age than the 1960s or 1970s.”

In light of this, Chipperfield’s first decision as artistic director has been the upstairs exhibition space at the new Driade showroom, a white gallery mezzanine display floor currently full of pieces from the early years of the design company – including works by Enzo Mari (a beautiful glass-topped, bent steel-legged table with an industrial spirit, which could have been designed in 2015 and not the 1970s) and slightly more dateable work by the likes of Antonia Astori and De Pas, D’Urbino, Lomazzi.

Chipperfield doesn’t want to wallow in the past or be seen “as simply a reproducer of products”. But, he says, the best design is simply the best design, and it shouldn’t be ignored in favour of novelties. “My admiration for Enzo Mari has grown immeasurably over the past few months,” he says, having studied the archive. “His designs look as fresh now as they ever did. They are timeless. I wanted to remind ourselves of the traditions of Driade.”

And so the first “new” products Driade launched in April in Milan included the Elisa sofa and armchair (from £2,058) by Mari on high architectural metal legs to add to the beautifully classic Frate table series (from £2,670), which has always been a Driade bestseller, as well as a reissue of his Sof Sof chair (from £816), on a black wire frame. There’s also a new architectural ZigZag bookcase (from £2,364) from Konstantin Grcic, a new clocks-within-a-clock from Nendo (£249) and a mini slab coffee/side table (from £3,264) from Fredrikson Stallard to match last year’s Basalt dining table. New designers are being sought too. “We will use old ones, we will use new ones. We will use unexpected ones. We will work with whoever can keep Enrico’s spirit alive – that spirit of be generous, let people do their own thing.”

Interestingly – and ideally for him – Chipperfield doesn’t feel the need to prove himself financially. He says that even in his architectural projects, “I refuse to be involved in budget meetings and I never intend to be”. Indeed, to some extent he has already done what he was recruited for – to bridge the past and future direction of the company, to attract the international press and to show it is still a serious player. “I’m not a football manager. No one is going to get too cross with me if I don’t change the commercial fortunes of the company.”

Certainly Core isn’t. That is his job. By all accounts he is doing it well, investing via ItalianCreationGroup €7m into Driade, whose turnover grew 20 per cent between 2013 and 2014. Core differs with Chipperfield somewhat on the causes of difficulties within Driade. He doesn’t dismiss the economic slump, but he believes that “Italy makes some of the best products in the world, but doesn’t know how to make those products known abroad. Driade was never exploited in the way it should have been – not just commercially, but also from a brand image point of view.” He intends to change that not just for Driade, but also for a number of Italian family‑run businesses.

Core has spent the past 18 months or so bringing manufacturing back to Italy: “It doesn’t make sense to make sofas in Indonesia, when we can make the best here. Whereas it makes total sense to have our glassware made outside Italy by Czech Republic designer Borek Sípek.” He has restructured, reorganised distribution, focused on key markets beyond Italy – France, Germany and the US, where he opened ItalianCreationGroup USA in 2013 – and has already acquired his second smallish Italian business, Valcucine kitchens.

These are very big plans. But curiously, much of Core’s current path, and his decision to take on Driade, is as personal as Chipperfield’s. After 15 years in strategic consultancy and five in telecoms in the US, Brazil, Argentina and Europe, for him ItalianCreationGroup is all about fulfilling his own desire to further those heritage design brands he cares passionately about and has watched from afar for many years. “I was a Driade customer. I had huge respect for this company and its designs. I couldn’t not buy it. It has immense value to me beyond revenue. And for these reasons, I feel we can’t lose with David. We have already won just getting him on board. The risk with him is zero. Already six months in, I know 100 per cent that together we will do a great job.”

Alessi, alessi.com. David Chipperfield Architects, davidchipperfield.com. Driade, driade.com

Comments