Simone Rocha on Girls Girls Girls (and baby teeth)

Fashion can be brutal when it holds up a mirror to real life. Knowing that Simone Rocha gave birth not four months before the presentation of her spring/summer collection, Baby Teeth, is wince-inducing. While there is tenderness, beauty and maternal celebration at its heart – including takes on christening robes and homespun comfort blankets – this is definitely love with a twist. Said tiny teeth, crafted in porcelain and dangling from the ears, look like they have been wrenched out from the root. Blood-red ribbons swirl around skirts and stockings; supportive undergarments disrupt the pretty allure of negligees; and nightdresses, which open front and back, seem to have melded with the bedclothes in their sleep-deprived state.

It’s against this backdrop of “intense…really intense” lived experience that the 35-year-old designer (who celebrated the 10th anniversary of her label last year) and mother of two daughters – Valentine, six, and Noah Roses, now 10 months – has been nursing another project: her first contemporary art show as curator. More than two years in the making, Girls Girls Girls is a group show at the gallery in Lismore Castle, the historic home of the Duke of Devonshire’s family in County Waterford. It’s an “exploration of femininity and its subversions, the female spirit and its experience” – which, in Rocha’s hands, is as compelling as it is timely.

The exhibition is part of Lismore Castle Arts, a non-profit initiative by the duke’s son William, Earl of Burlington, and his wife Laura, which presents a roster of contemporary art each year. “The fact it’s in Ireland is a big attraction,” Dublin-born Rocha says. “I’m incredibly proud of being Irish, of being educated there, of its arts institutions, and I follow the work of a lot of upcoming artists. A project like this impacts on the community, so it felt like a great thing to do – more so than to make any sort of political statement about female artists.”

Her show, supported by the gallery’s director, Paul McAree, was designed as “a conversation between generations and diverse perspectives”, bringing together the work of world-renowned artists – Cindy Sherman, Roni Horn, Louise Bourgeois and Holocaust survivor Alina Szapocznikow among them – and that of a younger group of lesser-known creatives. “Simone respects and is so keen to promote other creatives, and she does it in a beautifully understated way,” adds Laura Burlington.

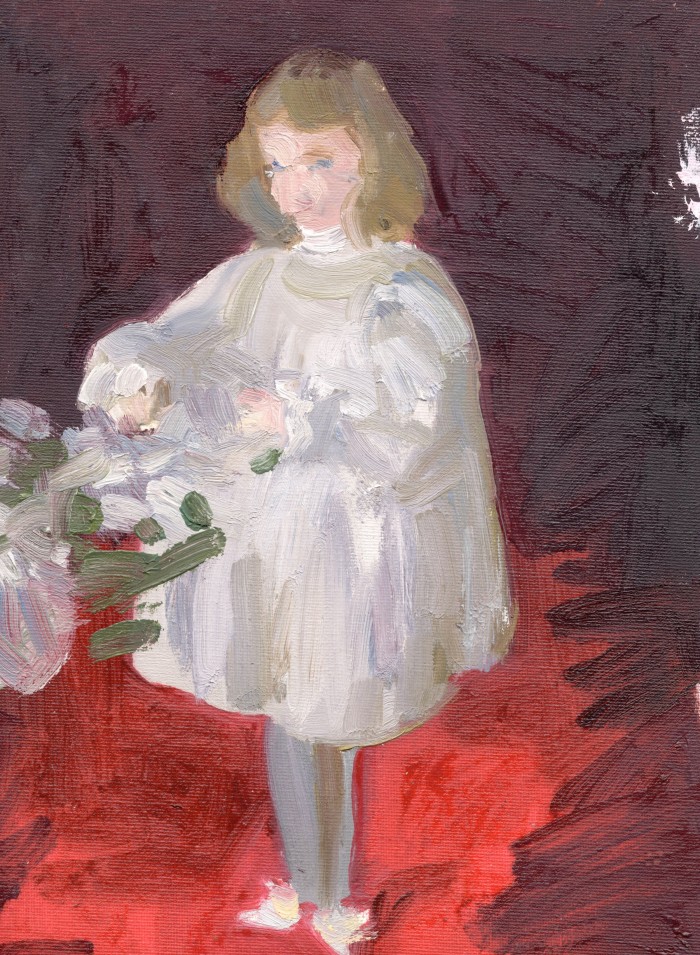

“I’m very aware that I’m a fashion designer bringing together these different works,” says Rocha. “It felt most honest to pick pieces that I feel very connected to.” While she was growing up, her parents’ own collection could hardly escape her – John and Odette Rocha favoured Sean Scully, Picasso, Matisse and Lucian Freud – but it had “a very linear progression – quite monochromatic, lots of line drawings”, she says. “The kind of imagery I was attracted to was softer, more feminine, but more visceral and provocative too. It’s Francis Bacon all the way to the Irish painter Genieve Figgis.”

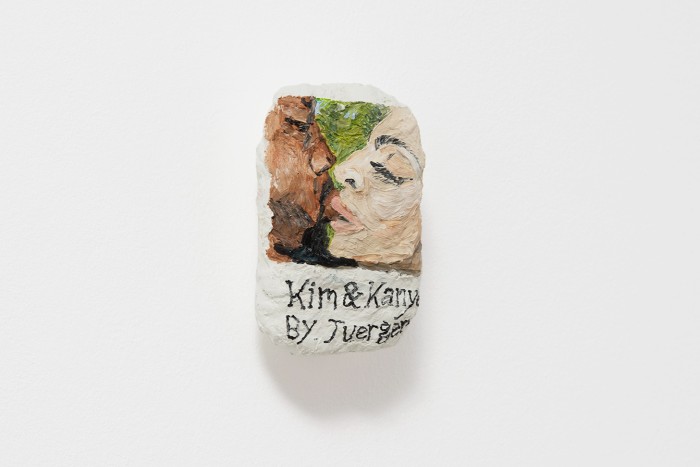

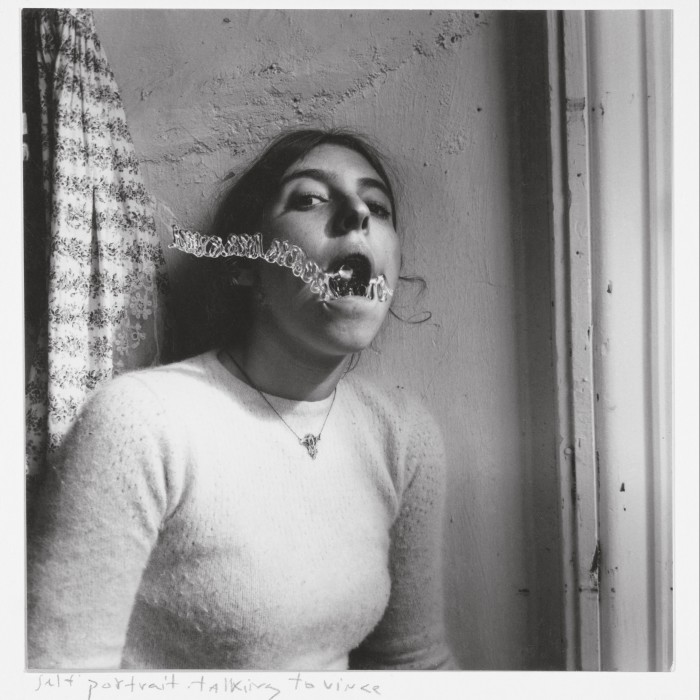

Sometimes anguished and harrowing, but often poignant, even witty, the show at Lismore acts as an imagined dialogue between the artists as well as chiming with Rocha’s tastes and sensibilities. “I wanted there to be a combination of works like Cindy Sherman’s bus-stop portraits, which are from a different era but feel really present, with newer work by artists like Sophie Barber and Josiane MH Pozi that has a really ‘today’ gaze but feels, at the same time, like it has a rich history. You’ve got Francesca Woodman, who died when she was very young, so her work feels almost like it was frozen in time. Then Roni Horn is so playful – she takes it to a tongue-in-cheek place. The works don’t flow into one another, but they come together to say something about strength.”

Unsurprisingly, there’s a tactile quality throughout: “With clothes it’s about touching, wearing and feeling, but with art it’s ‘Don’t touch!’ – that interested me.” There’s also a thread of “garment-driven” work, from the voluminous gown in Sian Costello’s Wishful Self-Portrait III to Tochter Der Schwester Der Mutter (Niece) by Iris Häussler – a floral dress encased in wax that Rocha was dying to include. “With a lot of the works there’s this idea of the physicality of a woman,” she explains. “Although some of the art transports you to a dreamlike place, it’s always brought back to reality with a shoe, or a foot or a breast.”

Or a pair of hands – in this case, in bronze, one of two powerful sculptures by Louise Bourgeois, whose influence the designer has worn on her sleeve for years. She’s still energised by the 20-year-memory of the diminutive powerhouse’s Stitches in Time show in the Irish Museum of Modern Art, near where Rocha studied a multi-disciplinary arts course at Dublin’s National College of Art and Design. “I was blown away by the fact that this was sculpture, but in textile form. The pieces were so sincere but they didn’t feel ‘crafty’; they were so provocative. And the opposite of serene.”

Bourgeois died the year Rocha showed her Central Saint Martins MA graduate collection at Somerset House and London Fashion Week, but her spirit has been woven into the fabric of Rocha’s practice ever since. She can’t believe her good fortune “to have gone from fan to collaborator”, working with the late artist’s foundation on jewellery inspired by her figurative forms, incorporating some of her textiles into her own collections and hanging her work in her stores.

“For me, femininity has always been about strength and fragility together,” says Rocha. She’s ever-conscious of this, as someone who makes her own imagery alluding to the feminine condition – and as a mother of daughters. “That responsibility comes down to being as honest as possible about both sides, I think… the need to have both in life, to balance each other.” That, and perhaps a little more sleep.

Girls Girls Girls runs from 2 April to 30 October

Comments