UK gender pay gap: stand by to compare the data

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The deadline for the UK’s second year of gender pay gap reporting is approaching fast. With it comes the prospect of taking stock on whether such an exercise in data gathering and analysis can help eradicate the difference in what women and men are paid, as the government intends.

“There’s going to be a lot of interest in the figures, because there’ll be that question of how they compare to the year before,” says Rebecca Hilsenrath, chief executive of the Equalities and Human Rights Commission, responsible for enforcing gender pay gap reporting.

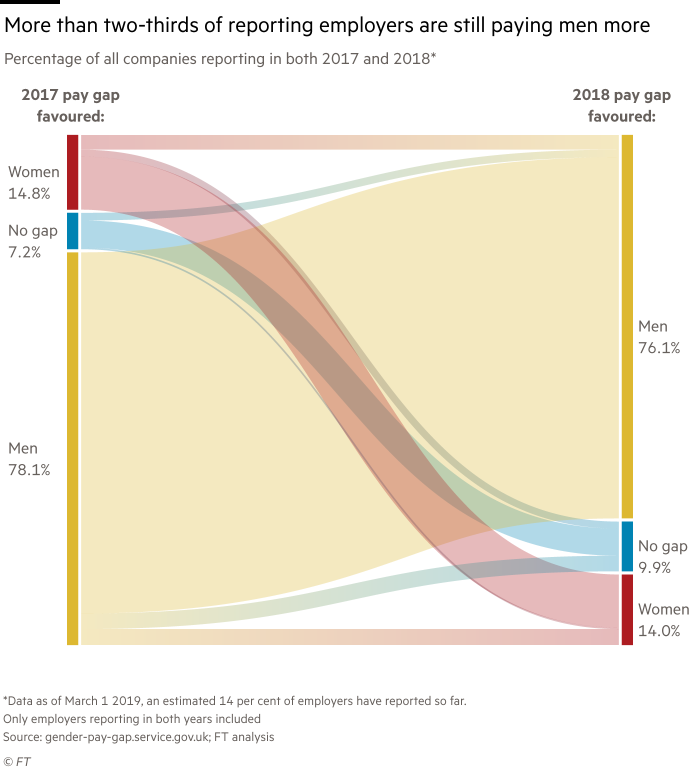

As last year, some companies have submitted their data to the government site ahead of the deadline, but most have not. The data published so far for 2018 show only a slight narrowing in the overall median gender pay gap: 11.1 per cent, compared with 11.8 per cent in 2017.

Only about 14 per cent of companies have submitted their data so far, but when those are matched with the same reporting group from 2017, the gaps overall are narrower.

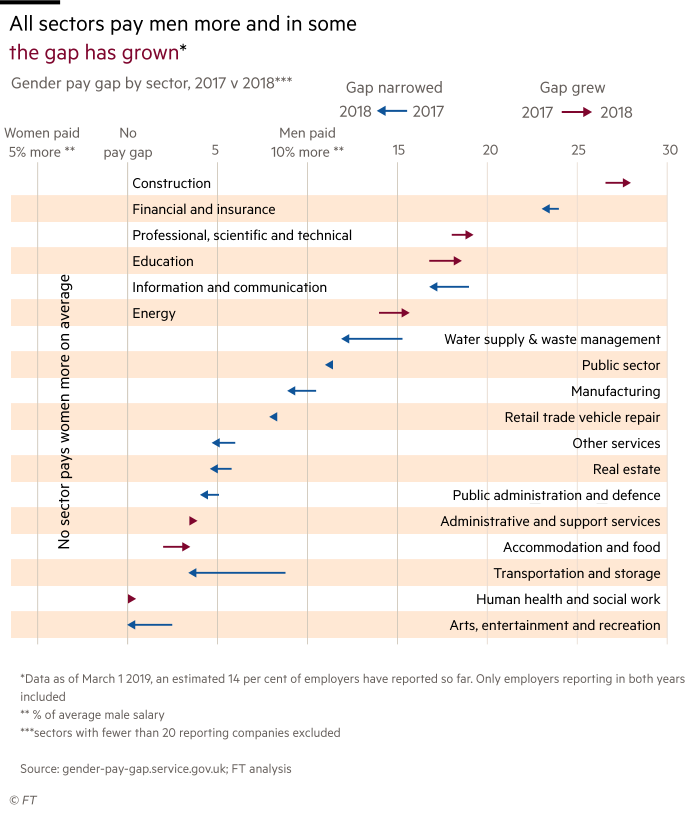

Although the data form only a picture of the reporting so far, the worst performing sectors (excluding those with fewer than 20 employers) are: construction, financial and insurance; and professional, scientific and technical (see chart).

Ms Hilsenrath welcomes the discussion and insights generated by the exercise. However, “the key thing is what happens next. It’s the data that determines the [company’s] action plan.”

Some 1,463 employers had filed their data by noon on March 1, ahead of the April 4 deadline. Last year, when filing became mandatory for those with more than 250 employees, a total of 10,537 reported. Some found it a scramble, and a number missed the deadline.

Eligible companies had to report their mean and median gender pay gaps, bonus pay gaps, and the proportion of men and women in each pay quartile and receiving a bonus. They have not, however, had to publish a narrative providing context or an action plan outlining how they will address disparities. Although businesses have been encouraged to do so by the government, only one in five submitted action plans by the end of 2018, the EHRC says.

Since the headline figures emerged nearly a year ago, the data have been digested further. Critics have highlighted anomalies in some data submitted by employers and called on regulators to do more to ensure accuracy. They also point to inaccurate reporting of the bonus gap, and the absence of data on equity partners in businesses such as law firms. More broadly, many have concluded that the reporting requirements are too weak to force companies to help close the UK pay gap.

“Unless businesses see there are consequences to breaching equal pay law it’s difficult to see why they would see gender pay gap reporting as anything other than a box-ticking exercise,” says Maria Miller, chair of the parliamentary women and equalities committee. The committee will report this year on whether the EHRC is making the best use of its enforcement powers.

The EHRC can act against companies that fail to report or misreport their data. But there are no formal sanctions or incentives for failure or success in narrowing a company’s gender pay gap.

Denise Wilson, chief executive of the government-backed Hampton-Alexander review of women in senior leadership positions, believes companies are taking gender pay gap reporting seriously and that the exercise has put the problem on boards’ agendas.

However, she would like more companies to recognise the link between the lack of senior women in businesses and poor gender pay gap results: “Unless they’re actually appointing women into their most senior roles, nothing changes.”

One welcome development is that even in sectors with a big gap, such as airlines, which overwhelmingly employ male pilots, some companies have tried to be transparent.

EasyJet had a median gender pay gap of 45.5 per cent in the first year of reporting, one of the worst reported by companies overall. The airline says that while gender pay gap reporting highlighted the problem to the industry, it had begun reporting figures voluntarily in 2015 and set a target that a fifth of new pilot hires must be women by 2020, for which it is on track.

At the same time, gender pay gap figures can also disguise problems. Consumer goods company Reckitt Benckiser’s own report recorded a median gender pay gap of 0.1 per cent in 2017, but this figure includes staff not employed by the six entities it reported data for.

It was identified by Hampton-Alexander as one of the companies with the lowest proportion of women in senior leadership. However, Reckitt published an action plan last year and expects to do so this year. Since 2015, it revealed, it has introduced initiatives such as flexible working and leadership development.

While Ms Miller would like “a sharper stick” than she thinks pay gap reporting is providing, Ms Wilson is more patient: “Once we start to get into years three and four, if the status quo remains and companies are very poor on diversity then there has to be some comeuppance,” she says.

Comments