Targeted action can stem the illegal wildlife trade

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Life on Earth faces two interlinked environmental crises. While climate change is receiving most attention, politicians and public must also face up to the alarming loss of biodiversity worldwide — what biologists are calling the sixth great extinction since life began. We have lost 60 per cent of wild animals since 1970, and the total biomass of humans and farmed livestock today is 20 times greater than all the world’s wild mammals put together.

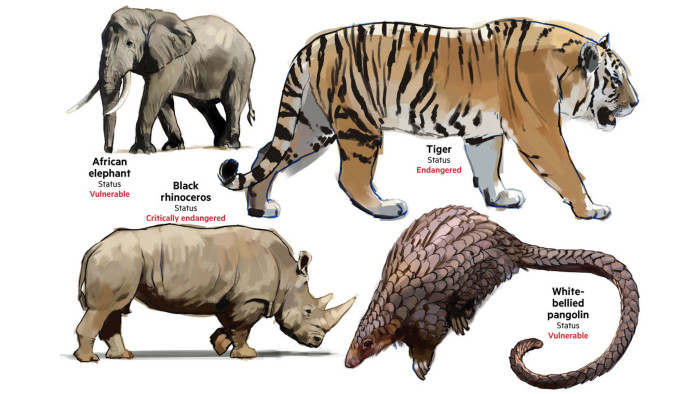

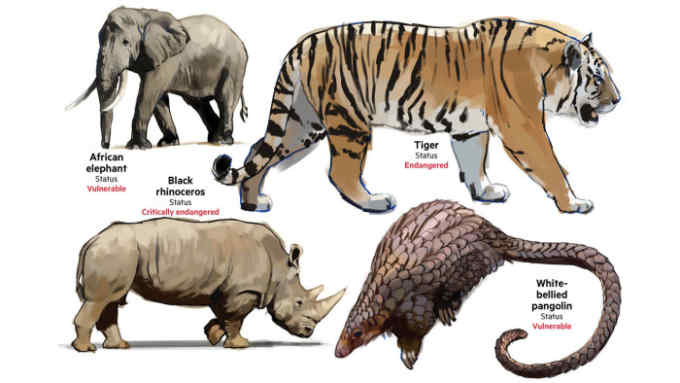

Protecting wildlife from some of the factors responsible for the biodiversity crisis — including climate change, pollution, the loss of uncultivated land to agriculture and urbanisation, and the spread of invasive species and pathogens — is a formidable long-term challenge. However, targeted intervention to prevent another cause of rapid decline in many species, the illegal wildlife trade, could give more immediate results.

Advances in technology provide new opportunities to stop the poaching that is devastating wildlife across large swaths of Africa, Asia and South America, as gangs kill animals for meat, horns, tusks, teeth, bones, scales, fur and other products for the black market. The tech industry was slow to enlist in the battle for biodiversity. But companies such as Google, Intel and Microsoft are now helping conservation bodies including the Zoological Society of London — the FT’s Seasonal Appeal partner for 2019-20 — to develop camera traps with connectivity and artificial intelligence, which can alert rangers and wardens instantly when intruders with guns or knives are detected.

Resolve, a Washington-based conservation charity, estimates that the equipment and infrastructure to protect 100 of Africa’s most important parks in this way could be installed for around $4m. But much more money will be required to help many grossly underfunded parks to manage the system well and employ enough staff for effective enforcement. This might have a deterrent effect on potential poachers.

When anti-poaching measures fail and animals die, advanced forensic science, including new methods of fingerprinting and DNA analysis, can be used to track down criminal gangs handling products from ivory to pangolin scales.

Even the most brilliant applications of science and technology will not save wildlife on their own. Economic measures and legislative action are also required to reduce supply and demand for wildlife products.

People will have less incentive to tolerate or take part in poaching if they have a financial stake in sustaining healthy populations of live animals. In some places this may be achieved through a model of sustainable tourism that rewards local communities. To help preserve more remote areas, government and philanthropic donors should consider a global biodiversity financing mechanism, perhaps modelled on the Amazon Fund that aims to slow deforestation of the Brazilian rainforest.

At the same time countries that consume illegal wildlife products, particularly in Asia, must intensify their efforts to put an end to practices that often have traditional roots but have experienced an increase in demand as people become wealthier. The worldwide movement to close down the legal ivory trade, which has been a cover for poached ivory, must accelerate.

Although the inevitable encroachment of a growing human population on wild land makes a sustained revival of global biodiversity unlikely, selective action against the illegal wildlife trade can lift the threat of extinction from some of the most distinctive species alive on Earth today.

Comments