Uzbekistan’s population boom poses problems for state

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

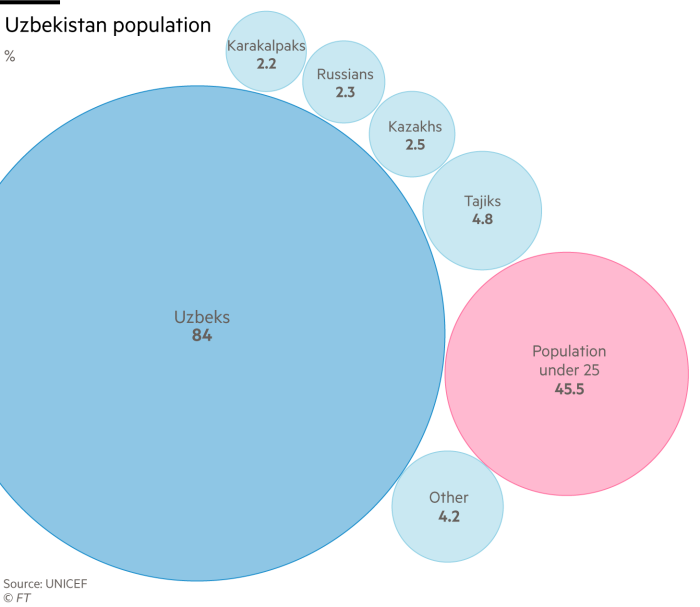

Uzbekistan is a young country: last year, more than 800,000 babies were born — nearly 25 per cent more than in 2010. According to a recent Unicef report, at least half of the 33.5m population is under 30, which makes the current labour force the largest the country has ever had.

By 2046, the working-age population is expected to reach 27m, and jobs must be found for them. But there is an even more pressing problem: youth unemployment is currently running at a rate of 15.2 per cent — 1.5 times higher than average. Many young people leave the country in search of better jobs.

The government’s response has been to set 2021 as the “Year of support for youth and public health promotion”.

Last year, the state’s youth policy — a set of directives introduced in 2016 — was reformed to include a range of measures, such as free training and grants for businesses and start-ups, and subsidies for young people working in agriculture in rural areas, where half the population lives.

It also mandated “involvement of young people in culture, art, physical education and sports, increasing their literacy in information technology, promoting reading among young people, and ensuring women’s employment”.

In Uzbekistan, the International Labour Organization (ILO), a UN agency, found that 33 per cent of working-aged women are engaged in unpaid care work as their main activity.

According to the government, 1.4tn som — about $131.5m — has been spent on youth policies since the reforms were announced.

The objective was boosting “modern entrepreneurship skills and creating new jobs”, as well as preventing “juvenile delinquency and crime, preventing family divorces, forming a strong idea of patriotism and a firm civic position”.

The government’s Agency for Youth Affairs was set up last year to oversee these objectives. Its director is Alisher Sadullaev, a 27-year-old Uzbek graduate of the Management Development Institute of Singapore in Tashkent, who in 2017 became Uzbekistan’s youngest deputy minister at the Ministry of Public Education.

Sadullaev says the problems in improving education are different in urban and rural areas. In the latter, schools lack basic infrastructure such as electricity, gas and clean drinking water.

Education in Uzbekistan is compulsory to the age of 18, but in practice the school system does not always function adequately.

Unicef’s report says: “At school, now there are teachers who do not know their subject very well. Because of them, schoolchildren receive little knowledge, and parents are forced to spend money [on private tutors].”

Often, pressure to generate income for families means university is not an option — particularly for children in rural areas.

Last year, the government introduced vocational training for unemployed people and those who completed ninth grade (roughly aged 15-16).

There is also a focus on higher education, with an ambitious target for half of all school children to enter university by 2030. New scholarships are part of the push, with $200m in grants and scholarships for students enrolling in foreign universities, and increases to student loans at home.

But corruption in the school system still affects families and students. According to Unicef, teachers ask for bribes for grades, adding to the financial pressures many students and families face and leaving many children and students falling behind.

In the past, Uzbekistan also has been criticised by NGOs for lack of action against forced child labour working on cotton harvests, an old practice condemned by the current president. The US lifted its ban on cotton imports from Uzbekistan in 2019, after the Uzbek government acted on promises to clamp down on the practice.

In 2019, new regulations brought in inspections and criminal penalties. This year’s independent monitoring report from the ILO, found that most people interviewed reported that in 2020 “the risks of forced labour were much lower”, though some local practices remain.

Sadullaev says the “year of youth” is designed to help tackle the stubborn problem of youth unemployment. Future labour market statistics will show if these efforts make an impact.

Comments