FT writers: what I would like to tell you about Alzheimer’s

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This year the staff of the Financial Times have voted for Alzheimer’s Research UK to be our Seasonal Appeal charity partner.

At the moment there is no cure for this devastating disease, and almost 50m people around the world are living with dementia.

But research towards a life-changing treatment is making progress and, gradually, Alzheimer’s disease is coming out of the shadows.

Here, five journalists from the FT tell their own family stories. We hope that you will share your experiences too.

Leyla Boulton: my mother, Irene

My mother Irene lived a varied and interesting life that ended last month with a death that spared her the worst of what dementia has to offer.

All but one of the few friends who had remained in touch after she suffered a stroke in 2012 stopped visiting once dementia — a brutal and relentless invader — arrived three years later.

As this cruel disease gradually narrowed what my mother and I could do at weekends — knocking out first the opera, then the cinema and then making for very rapid tours of museums before she started shouting made-up words that meant sense only to her — my mother retained something of her mind until the very last.

That was important to a woman who throughout her life valued compassion, learning and intelligence.

I particularly remember my husband Ralph, a charmer of old ladies, talking to her on the 73 bus as we headed towards the British Library’s exhibition on the Russian Revolution. “Do you remember Mr Stalin?” he asked Irene, whose family fled communist Russia. “Yes, he’s the one who ruined the Russian Revolution,” she replied. Ever hopeful of my wheelchair-bound mother’s capacities, I then started telling Irene, a news junkie most of her life, about how Donald Trump had just fired the head of the FBI. “Who’s Donald Trump?” she exclaimed.

When the passengers sitting next to us on the bus burst out laughing at the idea that at least somebody was oblivious to the noisy US president, they made me feel my mother was part of the world rather than excluded from it. As recently as January, when my mother took part in the women’s march against Trump, she still knew who he was.

By July my mother was admitted to London’s University College Hospital with an infection of the nervous system. The valiant young consultant who spent five weeks saving Irene summoned me to a meeting as he prepared to discharge her. He informed me that because of her worsening dementia, Irene could no longer remember how to swallow properly. This put her at permanent risk of developing a new chest infection if she ever inhaled her food, unless we fed her with a tube through her nose or stomach.

When I replied that my mother, whose advance wishes document had been seen by the doctor, would want neither, he set out a surprising alternative. He could arrange for a palliative care plan to ensure Irene suffered no pain if antibiotics administered at her care home failed to cure her next chest infection.

On the evening of October 23, my mother passed away peacefully after 10 days of palliative care, surrounded by her children and her beloved carer Beverly in the familiar surroundings of her room at Bridgeside Lodge nursing home in Islington.

I am grateful to the medical professionals whose enlightened approach enabled Irene to have as good a death as she could have hoped for in the absence of a cure.

Leyla Boulton is editor of FT Special Reports

Madison Darbyshire: my Grandma Jean

If I could tell you one thing about Alzheimer’s, it is that it is not an old disease. It is not defined by the trappings of age, like stiff joints and gnarled knuckles, though they may inhabit the same body. My Grandma Jean is absolutely certain she is not a day over 17.

She became young in the summer of 2016. First, she became obsessed by getting a bicycle. Not just any bicycle, but a blue one with a brown leather seat. Then, she started to ask when she could go home.

Has someone close to you been affected by Alzheimer’s?

Tell us about your experience with the disease here.

As a teenager, Jeannie was a Radio City Rockette, considered at the time to be one of the most elite and glamorous dance troupes on earth. She rode the bus each morning from her parents’ home in working-class Queens, New York, to Rockefeller Center in Midtown Manhattan. She can still tell you the exact bus route she took, although she cannot remember the name of her live-in carer. Each evening, Jeannie’s father picked her up and drove her home.

It is a small kindness that my grandmother inhabits such a happy time, years before the heartbreak of becoming a new mother and widow in a single season, before she remarried a man who beat her, before she quit dance to drive a school bus.

But now, my teenage grandmother wants to go home to Queens. Each time a car pulls up outside the small flat where she has lived for the past decade, and whenever the doorbell rings, she asks if it is her father arriving to drive her home.

Jeannie’s memory did not make a linear regression through time, systematically slipping back to the beginning. Alzheimer’s is like a series of fractures, a kaleidoscope of history that has been dropped, leaving the glass frames shattered and colours blurred together. My grandmother occupies many periods of her life simultaneously. She recognises and tries to parent her adult children, while still a child herself. When someone tells her that her parents have long since gone, my grandmother suffers the loss as if for the first time, again and again.

She lashes out, as teenagers do, at those who love her most. Alzheimer’s has forced the painful reversal of parent and child on my mother and her siblings faster than feels fair.

We are lucky, my grandmother experiences each new thing — visitors, a bag of chocolates on the table, a lunch order she has long forgotten making, a physician re-entering the examination room — with the delight of a child, often multiple times in the same hour.

On the car ride home from our last visit, I called my Grandma Jean to tell her I love her.

“I missed seeing you today,” she said, our time together already vanished into the cracks between memories.

Madison Darbyshire is editorial intern on the Comment and Analysis desk

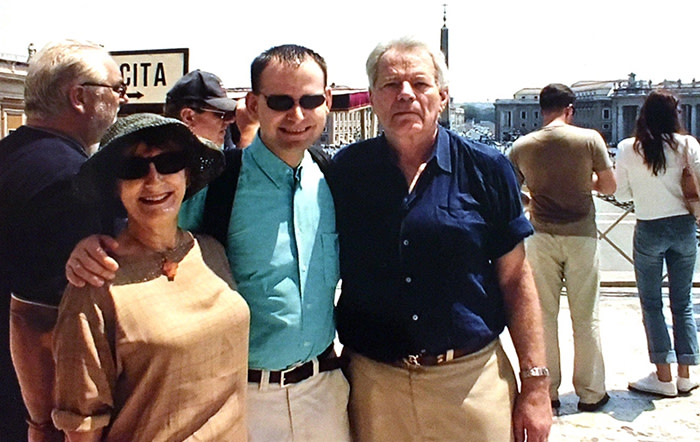

John Reed: my father, Joseph

When I was growing up, my father Joseph Reed cut a formidable, quirky figure at Wesleyan, the New England liberal arts university where he taught. He was loved or feared — sometimes both — as a professor of English literature and American studies. He was in charge of the “Language of Film”, the main cinema studies survey course taken by thousands of Wesleyan students over the years.

He wrote books, essays, and lectures on William Faulkner, Charles Ives, John Ford and the kitschy pleasures of bad poetry. He wore Ray-Bans and drank iced tea from a Samuel Johnson mug and rode a red bicycle around campus, and didn’t give a damn what you thought about that.

In the evenings, Dad painted fanciful pictures that drew on plant and insect life, pop culture and American history. Sometimes he brought home Hollywood golden age and French nouvelle vague films to screen for us in our living room. Of the three Reed children, I’m the one who looks most like him, and I think I’m the one who inherited his most charming — and irritating — traits.

About 15 years ago Germán, my husband, who is a nurse, and I noticed things were going south with Dad. He was as funny and eccentric as ever, but his driving was becoming erratic, his memory and concentration slipping, his wonderful handwriting unravelling. Soon the painting went too. As an FT foreign correspondent who returned home just once a year, I was able to see the deterioration more clearly, at least at first, than my mother. Many of Mom and Dad’s friends of decades began slipping away, perhaps too embarrassed or frightened to handle conversation with someone who was changing before their eyes.

As someone who grew up gay at a time when it was possible to be happy and open about it, I am struck by the stigma, awkwardness and euphemisms people use around people with Alzheimer’s and their families. Many friends of our family who know Dad’s diagnosis shrink from using the “A” word at all. But I also recently found out, to my anger, that one of Dad’s former colleagues recently mentioned his illness in dismissive terms in a class. Alzheimer’s is both the disease that dares not speak its name, and is fair game for offensive jokes.

Dad is now in full-time care in Los Angeles near where my brother and sister live. He is still good company and a unique soul (the carers love him). The old flashes of wit still come out at unexpected times. We are protective of Dad’s privacy, but open with friends in talking about his diagnosis, and active in supporting fundraising to find a cure. There is a big Alzheimer’s community to draw on — both nearby, as two members of Germán’s family have had it — and in the broader world. While my family lost some old friends when Dad fell ill, we’ve gained some wonderful new ones too. I’m delighted the FT chose this unfashionable but essential cause as our Seasonal Appeal.

John Reed is the FT’s Bangkok regional correspondent

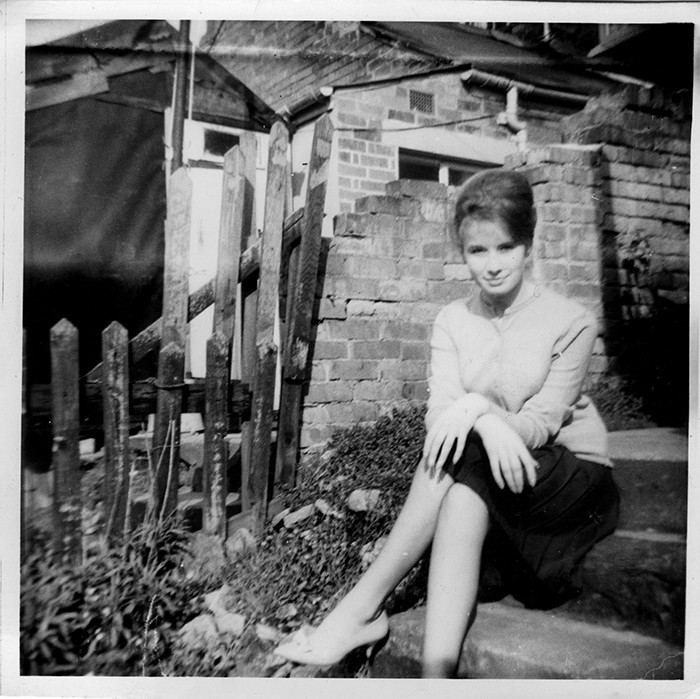

Helen Barrett: my mother, Glenys

My mother, Glenys Hughes, was clever, beautiful and exceptionally funny. The first two were useful for opening doors that in another time and place would have been jammed shut to young working-class women. In the UK postwar boom of the 1960s, clever young people could rise rapidly into the professional classes. And many employers, for one reason or another, like having good-looking women around.

But being funny was a double-edged sword. It made her magnetic, but could also make those outside her inner circle wary. Her wit seemed to come effortlessly and it could be caustic, like that of her class fellows John Lennon or the young Morrissey, whose lyrics she adored. Like them, she dispensed withering remarks with a glee that flowed from the realisation that she was brighter than those running the show.

Family and friends escaped lightly. Her choicest scorn was reserved for strangers — and she could be outrageous. Her targets were always the same: those she considered entitled, deluded or pompous.

A vivid childhood memory goes like this. I am seven and walking with my mother along a narrow pavement through a chichi town. Inches away, traffic hurtles past, and we walk in single file. A middle-aged couple stride towards us two abreast, their eyes fixed ahead, forcing me into the road, perilously close to an articulated lorry.

“Don’t get off the pavement, Helen!” my mother bellows. Then louder: “They’ve had their lives — you’ve got all yours ahead of you!”

She loved to recount her one-liners for our delight. Glenys was fabulous company.

The strange behaviour began five years ago. She abandoned her car in the road because it had broken down. When a friend went to retrieve it, it started straight away. She forgot how to put on a seatbelt, then how to open an envelope. She called me at work because she couldn’t find the tap. Glenys was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s at 69.

Within six months, the disease went into aggressive mode. She hallucinated during the day, and was tormented at night by paranoia and hysterics. Medication seemed to aggravate her condition. Within 18 months, she went from residential home to secure ward to nursing home, where she lives today.

Join Dementia Research

Anyone can help. Click here to find out how

I have heard Alzheimer’s described as a living death, but I am not sure I agree — certainly not for those close to the victim. Death is horrible but at least it is final. After a period of grief, loved ones live brightly in memory. Alzheimer’s is the opposite: the victim is right here, only their intellect, physicality and character are extinguished.

The one-liners are gone. Her Alzheimer’s is end-stage. She is docile and cannot speak or walk — it is as if she has been blotted away over the course of five years. She smiles at strangers, which is especially saddening for me.

Glenys is safe and well cared for by medical professionals. She is not exactly happy, but she is comfortable, which is about the most we could hope for.

And we know exactly what she would have said in any situation. We repeat her best conspiratorial asides and put-downs endlessly, and just for fun. But we keep them to ourselves.

Helen Barrett is editor of FT Work & Careers

Andrew Jack: my mother, Jean

We had long known that my mother had Alzheimer’s, but there was one surprise when we took her for a formal diagnosis in 2011.

She answered a series of tests of logic, comprehension and reasoning with little hesitation, performing as strongly as the intelligent and lively person she had been over many previous decades.

It was only when the psychiatrist asked her one apparently banal final question that her reply shook me: what year were we in? She replied “1950”, a point of reference of strong lingering memories from when she was a 22-year-old young professional.

Over several years, we had already observed her gradual deterioration: when she lost interest in newspapers, or never got beyond the same few pages of a novel; repeatedly bought books for my son far below his reading age; and occasionally wandered off down the road, on one occasion on to a train.

She stopped cooking and cleaning, and there were occasional tensions when my father, himself devoted to her but beginning to become physically weak, finally hired part-time carers.

Both he and she were at first concerned, but soon at ease, with the old people’s home into which she moved for respite care and then full-time residence. The staff were patient and empathetic, and luckily my parents had the savings to pay.

Whenever we visited, aspects of her personality came through even as she became ever more dependent and closed off from the outside world: she was calm and good-natured, co-operative and with a liveliness in her eyes often commented on by the staff.

She was also robust. The toughest part — as someone who had always been so chatty, gregarious and interested in her family — was seeing her declining ability to communicate and engage with others.

As she regressed to infant-like physical dependency, eventually to be spoon-fed, there was a growing social separation from the person we knew. Soon she had little conversation beyond an occasional “yes” or “no”, deteriorating to nods, and then no response except occasionally opening her eyes in response to conversation.

But her reply to the question about the year in which she believed she was living highlighted that everyone is on a continuum of self-consciousness and memory. The absence of any recall even straight afterwards did not necessarily nullify her pleasure in experiences and sensations in the moment — just as my own recollection of the details of events fades, albeit over a longer period.

The trope is that Alzheimer’s is when family and friends recognise it and suffer, while the person herself is unaware. It was sad for others to see her diminished. Yet the fact that she seemed surprised and not pained when we reminded her of her diagnosis on several occasions, suggested she was not haunted by the condition.

As we shared memories, told stories, read and showed her photographs; received a little squeezed response when holding her hand; or, until quite recently, fed her cake that she swallowed enthusiastically with her tea, I hope there was at least some quality of life and enjoyment in the instant for her too.

Andrew Jack is Head of Curated Content

Portraits by Charlie Bibby and Lauren DeCicca

• Your gift will be doubled

If you donate to Alzheimer’s Research UK through the FT’s Seasonal Appeal, Goldman Sachs has generously agreed to match it up to a total of £300,000. Click here to donate now

Comments