COP26: India’s coal habit proves hard to kick despite pressure to set climate targets

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The bone-rattling roars of nearby explosions rip through the air, shaking the ground and sending cracks up the walls of Dhan Kunwar’s brick-and-mud house. A few minutes’ walk away, her village gives way to the source of this daily cacophony: the opencast Gevra mine complex in central India’s Chhattisgarh state, one of the world’s largest coal pits. Police with long guns and military fatigues patrol the lip of the mine to protect the facilities.

Kunwar and her family are rice paddy farmers, but the encroaching mine has consumed most of their land. She and other locals have for years battled officials for better compensation, but the stress, pollution and incessant blasts used to break rock have worn them down.

“When you farm 50 or 60 acres of land, you get an enormous amount of [rice] paddy. But now we are cultivating only 10 acres,” says Kunwar, a member of one of the many indigenous communities living along a coal belt that stretches from central Indian forests to the country’s northeastern border with Bangladesh. “We have not benefited.”

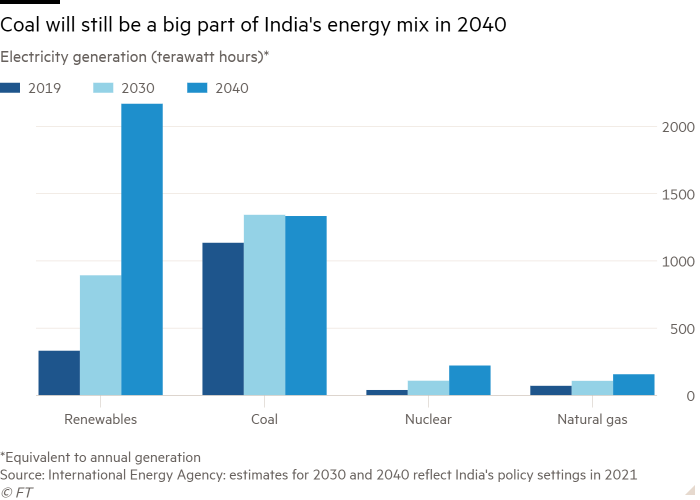

India’s energy demand is expected to grow faster than any other country in the world over the next two decades, according to the International Energy Agency, making the country of 1.4bn central to global efforts to combat climate change.

How much of this demand will be met with coal is the subject of a battle being fought all the way from Kunwar’s hamlet to the hallways of Glasgow ahead of the UN COP26 climate summit which opens on Sunday.

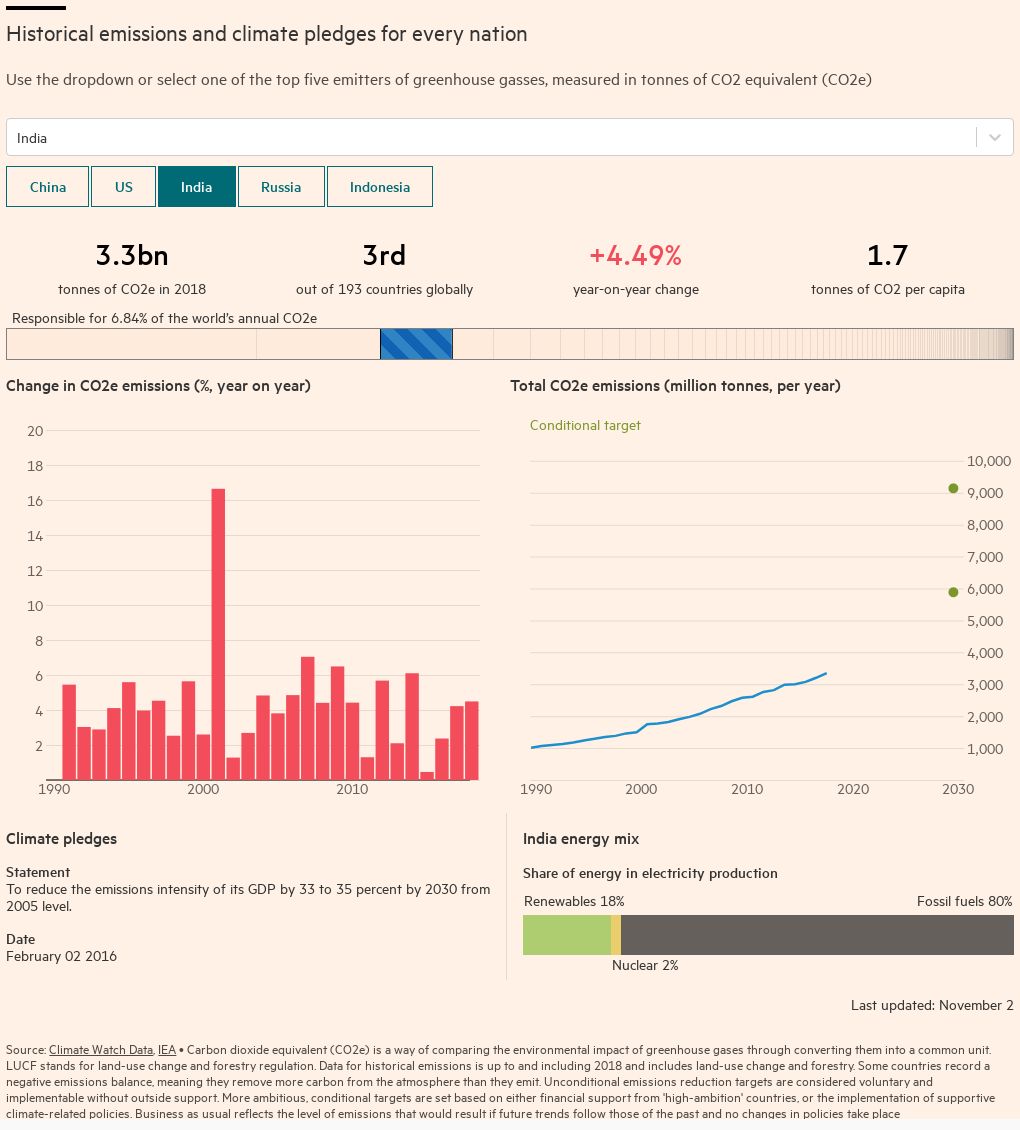

India is the world’s second-largest producer and consumer of coal after China, and the polluting fuel accounts for 70 per cent of its power generation. It is facing intense pressure to join countries, including China, in setting a net zero emissions target or committing to phasing out coal.

Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, has presented himself as a clean energy pioneer, setting an ambitious target to build 450 gigawatts of solar and other renewable capacity by 2030. Yet such a move would only reduce the share of coal to around half of all power generation, and mean that the quantity of coal consumed would actually increase.

“There is no short- to medium-term exit strategy for coal [in India],” says Rohit Chandra, a political scientist at the Indian Institute of Technology in Delhi.

Modi’s government — and many of his critics — argue it is for rich countries who have disproportionately contributed to global warming to do more. India’s power minister RK Singh has criticised developed nations’ distant net zero targets, arguing they need to quickly bring emissions below the global average and go “net negative”, absorbing more carbon than they emit.

In India, still a country with widespread poverty, millions struggle without reliable power supply. Per capita electricity consumption is a third of the global average, and per capita coal consumption is just a quarter of Germany’s, according to Future of Coal in India, a 2020 book.

More energy is needed to deliver growth and security to the country which does not have abundant alternatives like gas. “You want to always be cautious about saying ‘let’s kill coal’,” says Rahul Tongia, a non-resident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and one of the editors of the Future of Coal in India. “Let coal die when there’s an alternative that makes sense.”

In October India, like China, faced power cuts and crippling coal shortages due to supply mismanagement and a post-pandemic rebound in demand. The effect was to heighten anxiety about future energy security.

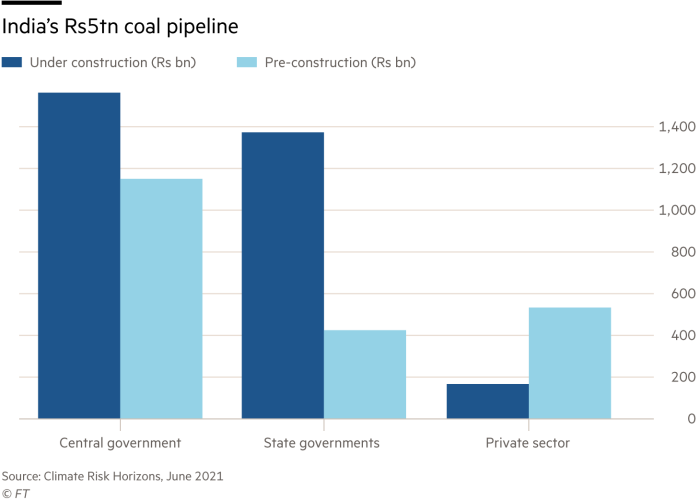

Yet critics say India needs to do more to reduce emissions. Coal-fired plants worth $60bn are under construction, according to Bangalore-based Climate Risk Horizons, despite concerns about excess thermal capacity. Although the country has the world’s worst air pollution, the government has repeatedly pushed back deadlines for coal plants to adopt stricter emissions standards. A study in The Lancet medical journal estimated that nearly 1.7m Indians died from toxic air in 2019.

“The rich nations doing their bit gets conveniently sidelined and all the heat [is] on developing countries . . . I see why India is taking that stand,” says Shweta Narayan, an India-based campaigner at Health Care Without Harm, an environmental health group.

“What I find disappointing is a lack of conversation about, ‘How are we going to phase out coal?’ What we’re seeing is this chest thumping on how good we are on solar, which is phenomenal, but that’s just one bit of a large puzzle that we’re not willing to solve at this point.”

Coal dependency

Buried deep beneath the soil of Chhattisgarh’s Hasdeo forest are rich coal reserves that have turned the jungle into the site of a bitter dispute over India’s future energy supply.

Nearby forest has already been felled to make way for the vast Parsa East & Kanta Basan (PEKB) mine, operated by billionaire tycoon Gautam Adani. Trucks bulging with coal wind through the red and beige sediment sitting atop the jet-black carbon below. More blocks in the dense jungle are set to be mined by the Adani Group, owner of the controversial Carmichael coal mine in Australia, on behalf of Indian state utilities.

Dashrath, a local goat herder, says the potential job opportunities from mining are attractive but he fears the destruction of a forest that sustains local indigenous communities. “What can we do, if the government wants to open it?” he asks. “Despite the opposition, mines have been opened.”

Coal is vital to India’s economy. The government receives billions of rupees annually in dividends from state-owned Coal India, the world’s largest coal miner. Indian Railways, the sprawling national railway company and largest civilian employer with over 1m workers, subsidises passenger tickets by charging more for coal freight, according to Tongia.

In India’s mineral-rich but under-developed mining belt, millions of people depend on the industry for work while political systems thrive on taxing both legal and black market coal. Korba, Chhattisgarh’s industrial hub, is full of busy restaurants and new SUVs thanks to the nearby pits operated by a Coal India subsidiary.

“The scale of the economic dependency and social dependency in these areas [is such that] if you snap your fingers and all this disappears, that means economic ruin,” Chandra says.

Yet mining has divided states like Chhattisgarh too. It remains among India’s poorest and is a hotspot of an entrenched Maoist insurgency.

The riches of coal also feed graft, with the illegal allocation of lucrative mining blocks in the mid-2000s sparking one of India’s biggest corruption scandals. More than 200 licences were cancelled by the Supreme Court in 2014.

Attempts to mine coal in Hasdeo have been fiercely resisted, leading to years of legal battles. Along with the PEKB block, mined since 2013, three others operated by Adani for Indian state utilities are under development. One received late-stage regulatory approval last week.

A report by the Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education warned that displacement of local people could lead to “loss of livelihood, identity and culture”. It advised against mining 14 of 23 proposed blocks in the area but judged that several, including three Adani-operated mines, could proceed.

“We’re being treated as colonies to help light Delhi and Mumbai,” says Sudiep Shrivastava, an environmental lawyer who has fought the plans. He argues that mining in the area is being pursued to suit corporate interests. “Are we bound to enrich Adani?”

A state official involved in the project says that “to cater to 1.4bn people . . . you have to think of the balance. You have to balance [local] needs and consumption also.”

Private champion

After years dominated by state entities, India is trying to increase private participation in the coal sector. Since last year it has been auctioning dozens of blocks for commercial mining, part of an effort to end imports of the polluting fuel, but received lukewarm responses from many investors.

The Adani Group has emerged as one of the largest private companies in coal, part of its swelling infrastructure portfolio encompassing power plants and airports. Its eponymous 59-year-old founder, the second-richest man in Asia with a $75bn fortune, has become one of India’s most powerful businessmen.

The tycoon enjoys a long relationship with Modi, both hailing from the western state of Gujarat. Adani is an enthusiastic cheerleader for the prime minister’s vision of a leaner state backed by strong corporate champions. But critics argue this proximity has helped the group in everything from winning government contracts to securing regulatory clearances.

Analysts say the alignment helps explain why Adani is one of the few private players willing to invest in coal despite the regulatory and reputational risks.

The Adani group denies favourable treatment, saying it operates under “a stringent regulatory framework” and is helping meet India’s growing energy needs. It has a growing renewable energy business and has said that it will invest up to $70bn into the sector over the next decade.

But its growing coal investments have sparked fierce censure and accusations of using renewables to “greenwash” its polluting activities, such as its Australian and Indian mines and coal plants. The Adani group rejects such claims as “absurd”.

“We remain and will stay aligned with the nation’s policies,” it says. “It is obvious that India is not in a position to phase out coal immediately.”

Several hundred villagers from Hasdeo marched more than 100 miles to Raipur, the Chhattisgarh state capital, earlier this month to protest against the planned mines. “Our existence, our culture, land, water — everything related to us is at stake,” says Umeshwar Singh Armo, 40, one of the protest leaders. “We wanted development but not at the cost of destruction of our villages and jungles.”

Adani says investment in Hasdeo brings jobs and development to an otherwise neglected region. On a company tour of the PEKB mine and adjoining corporate social responsibility projects, Vedmati Uikey says Adani helped her and 250 other local women expand a co-operative selling spices and garments.

Twice weekly newsletter

Energy is the world’s indispensable business and Energy Source is its newsletter. Every Tuesday and Thursday, direct to your inbox, Energy Source brings you essential news, forward-thinking analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here.

“Earlier we were terrified,” she says. But after the mine was opened “we started growing.”

But Sunita Singh, 30, a protester who risks being displaced by one of the proposed coal mines, says financial compensation cannot replace the loss of land which her community has long foraged and farmed.

“The money of coal will be burnt tomorrow,” she says, “what will I do then? We have survived on these resources for generations.”

Domestic and global pressure

Lobbying by the UK and other wealthy nations to force Modi — who will travel to Glasgow for the UN climate meeting — to commit to phasing out coal has so far yielded little. Some believe India is delaying making any pledges ahead of COP26 in order to negotiate more financial or technical assistance from rich countries.

China, the world’s biggest polluter which consumes four times more coal than India, has committed to a net zero emissions target by 2060 — a decade later than the UN’s 2050 target. But activists warn that without its own commitments India risks being branded a polluter despite low per capita emissions.

Yerlan Syzdykov, head of emerging markets at French asset manager Amundi, says India’s resistance to setting emissions targets risks hurting its appeal as a sustainable investment destination. “This is a very thorny question,” he says. “Their views are quite understandable, which I’m sympathetic to.”

U Kumar, former chair of the Chhattisgarh-based Coal India subsidiary, says India agrees in practice that “coal should be phased out for power generation”. But green energy sources to fuel heavy industry, such as hydrogen, remain a distant prospect.

“We’ll have to depend on coal . . . before we reach the stage when we can bank on renewables,” Kumar says.

India may not need as much coal power in the future as it thinks. Some analysts argue authorities have long overestimated demand growth and subsequently built more plants than it needs. Thermal power capacity grew at 14.5 per cent between 2011 and 2016, according to Tongia, more than double that of generation growth.

At the same time coal plant utilisation rates tumbled from nearly 80 per cent to just over half in the past decade, according to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis think-tank. It argues that unless upcoming plants replace older, inefficient ones, they will be unsustainable and add to the strain on an already financially stressed power sector.

Climate Risk Horizons argues that ultimately “allowing expensive, uncompetitive projects to continue to be built [is] often for political rather than economic reasons”.

Renewables are also becoming more competitive. Prices for solar and wind energy have fallen to around Rs2 per kilowatt hour, roughly half the equivalent of coal tariffs — though analysts say that doesn’t include the cost of integrating renewables into the grid.

Significant advances in battery storage are needed before renewables can become a backbone of the power system in India. But some argue coal is already in decline, regardless of India’s position.

“Irrespective of whether the government of India actually goes ahead in Glasgow and says we’re going to . . . phase out coal, the transition is already under way in India in an organic manner,” says Swati D’Souza, a researcher at non-profit group the National Foundation for India, which works on social justice issues. “[But] from a negotiation point of view, India would rather not take that stance. The politics of the coal economy makes it difficult.”

The looming challenge for Indian authorities will be managing this shift in a way that protects energy security, avoids bankrupting power companies and prevents economic devastation in the coal belt, analysts say.

“There are so many layers of people who will lose,” adds D’Souza. “If you don’t have a plan in place, then everyone [in the coal belt] loses.”

Additional reporting by Avdhesh Mallick in Raipur

As part of our coverage of COP26 we want to hear from you. Do you think carbon pricing is the key to tackling climate change? Tell us via a short survey. We will share some of the most interesting and thought provoking answers in our newsletters or an upcoming story.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Letter in response to this article:

How India’s conversation around coal has changed / From Pawan Mehra, Saratoga, CA, US

Comments