Rishi Sunak offers the obligatory Brexit bonus

This article is an on-site version of our Britain after Brexit newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every week

From a Brexit perspective, this week’s Spring Statement by UK chancellor Rishi Sunak provided a reminder of two enduring aspects of the UK political debate since leaving the EU.

First is the continued desire to try to show that Brexit brings benefits, even when (to put it kindly) those benefits are extremely hard to discern in the current trade and economic data, whether from new trade deals or any potential deregulatory dividend.

Despite this, Sunak still used his speech to score an obligatory Brexit bonus point with his backbenchers by flagging that a decision to zero-rate wind and water turbines for VAT was made possible only because “we’re no longer constrained by EU law”.

Like Sunak’s pledge in last October’s Budget to revamp alcohol duties as a result of new-found Brexit freedoms, the offer spoke unwittingly to the paucity of the Brexit dividend thus far.

Just how thin was made clear on Wednesday by the Office for Budget Responsibility, which still finds Brexit will have a 4 per cent negative long-run hit to gross domestic product, and that all the new trade deals and deregulatory plans announced will have zero “material impact” on that forecast.

And then, for the second part of his Brexit one-two, the chancellor noted that because of the “deficiencies” of the Northern Ireland protocol the VAT cut on green tech didn’t apply to the region, promising that Brussels would be confronted over this as a “matter of urgency” (watch out for a resurgence of Article 16 chatter in the coming months).

What is striking is that, for all the exhortations from Brexiters for the country to “move on” from Brexit, the chancellor-that-would-be-prime-minister finds himself stuck in the same old Brexit rut.

But this is not just about rehashing old arguments, it’s about the arguments to come.

Far from drawing a veil over the manifold costs of Brexit — something potentially made easy by the pandemic and now a war in Europe — the Conservative party is determinedly still pressing that political reflex.

It was notable when Boris Johnson was most under the pump at the despatch box over “Partygate” earlier this year, he kept repeating that he had “got Brexit done”, as the first and best defence of his record. And looking ahead, it seems Brexit is being chosen as the battleground for the next election too.

According to The Times, the election strategist David Canzini has told No 10 staffers that “delivering on the promises of Brexit” is number one in a list of five election priorities — sitting above even the cost of living, NHS, crime and illegal migration. “If you don’t think that’s a priority you shouldn’t be here,” Canzini is reported to have said.

That might seem an odd priority, given how easily Brexit’s critics could argue that — to quote Meg Hillier, the chair of the public accounts committee when launching a recent report on Brexit effects — “the only detectable impact so far is increased costs, paperwork and border delays”.

But focusing on concrete delivery is to miss the political point, which is that (in the view of Tory political strategists at least) the Brexit issue can still trigger the partisan reflexes that delivered so handsomely for Johnson in 2019.

And those identities are sticky. In their recent paper for UKICE, Do ‘Remainers’ and ‘Leavers’ still exist? Sara Hobolt and James Tilley found that among those who voted in the 2016 referendum 69 per cent held a “Brexit identity” at the end of 2021 — down only from 75 per cent in April 2017.

Which is why outlandish claims from Brexiters — from the £350mn figure on the Leave campaign bus to likening the war in Ukraine to a vote for freedom from Brussels as Johnson did last weekend — works as part of a strategy to stir up that identity.

As Rob Ford, politics professor at the University of Manchester, puts it: “It’s about getting to ‘us v them’ politics, to stimulate ‘Leave’ partisanship.”

And in some ways, the more outlandish the claims the better. “It’s irresistible catnip for Remain partisans, who will rush to say how ridiculous and facile these claims are about the benefits of Brexit, and how ‘stupid’ you Brexiters are for listening to them,” Ford added.

If it works, the effect will be to retrieve those Labour Brexiters who voted Conservative in 2019 but are now drifting back to Labour. It also creates a partisan “Brexit lens” through which the same economic data look rosier to Brexiters than Remainers.

Will it work? Well, there is of course an obvious risk for Johnson in rerunning the 2016 and 2019 Brexit playbook, which is that his government looks trivial and out of ideas set against a cost of living crisis and a war in Europe. Voters may have moved on.

“That’s a risk,” said Ford, but equally he wouldn’t underestimate the degree for which Brexit partisanship is still the strongest form of political identity out there.

Still, it is an approach that requires a kind of political nihilism that Anand Menon, the director of the UK in a Changing Europe think-tank, captures with a football fan metaphor. “It’s like me, as a Leeds fan, saying ‘I don’t care if we don’t win anything, just so long as Man Utd don’t either’.” Anything, just so long as the Remain tribe doesn’t win.

It’s hard to know, given the state of politics, whether we can get to a better place where facts on the ground — as they did previously with the uncontrolled EU labour migration — do actually feed into the political debate.

Because as countless business surveys attest, and the data show, Brexit is a drag to the economy, to future prosperity and the chancellor’s righteous ambition to increase UK productivity — it’s just that neither of the two main parties really dares say so.

As Menon puts it: “We talked incessantly about east London plumbers being undercut by Polish plumbers, and now loads and loads of people in business are talking about Brexit damaging them, but collectively, we’re just not talking about it.”

Labour had failed to move the argument on, said Menon, by reframing the wider political debate along the lines of “you weren’t stupid for voting for this, but there are ways to do this which are less damaging”.

The reasons for the inertia are not hard to discern: Conservatives don’t want to dwell on the real costs of erecting barriers with the UK’s largest trade partners; while Labour still wants to skirt a political issue that continues to divide it as much as it unites its Tory opponents.

But that means that six years after the vote — potentially eight years by a 2024 general election — it’s hard to avoid a sinking feeling that we are where we were.

Do you work in an industry that has been affected by the UK’s departure from the EU single market and customs union? If so, how is the change hurting — or even benefiting — you and your business? Please keep your feedback coming to brexitbrief@ft.com.

Brexit in numbers

The Office for Budget Responsibility’s economic and fiscal outlook that was published alongside the Spring Statement provided a salutary corrective to much of the government’s rhetoric about the benefits of Brexit from trade and deregulation.

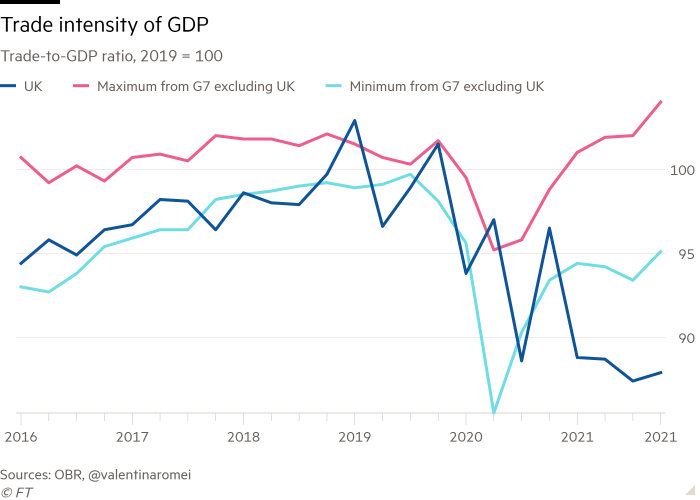

The OBR continues to forecast that leaving the EU will see total imports and exports 15 per cent lower than if we’d stayed in the EU, and that this “fall in the trade intensity of UK” will mean that UK productivity will be 4 per cent lower after a 15-year period.

When you measure UK performance against the G7 (which also experienced Covid) it turns out that trade as a share of UK GDP has fallen 12 per cent since 2019 — two-and-a-half times more than in any other G7 country.

And as for the compensatory uplift of the “Global Britain” trade agenda and the benefits of being freed from Brussels red tape, the OBR is deliciously deadpan: “None of the new free trade agreements (FTAs) or other regulatory changes announced so far would be sufficient to have a material impact on our forecast.”

Don’t suspect you’ll read much of that in the 2024 Conservative party election manifesto — or on current form, in the Labour party’s either.

And, finally, three unmissable Brexit stories

There is lots of FT commentary on Sunak’s mini-budget. Robert Shrimsley highlights who is inside and outside the Tory tent following the chancellor’s statement while Martin Wolf assesses the impact on living standards. Helen Thomas asks what the statement means for business.

The war in Ukraine has raised questions about the UK’s energy security. The Lex team this week delved into the opportunities and challenges presented by the North Sea’s energy reserves, with some arresting charts.

Finally, an experiment. My colleagues on Unhedged invited Adam Tooze, a Columbia professor and author of the widely read Chartbook newsletter, to discuss the pros and cons of China’s economic model. The column raises some important questions.

Comments