Flexible working’s unforeseen tensions

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

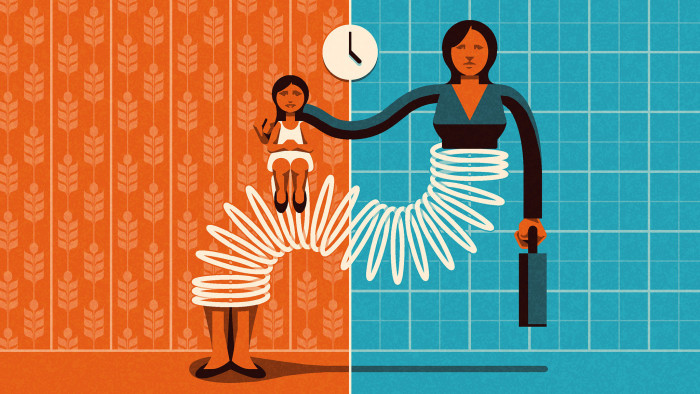

Flexible working bends outdated rules governing the time and place for getting work done. It helps employees who want to meld their career with competing responsibilities and interests outside the office. It is deemed useful to women especially, as they generally shoulder the greater proportion of caring responsibilities.

In practice, however, employees and organisations are finding that flexible working involves navigating unforeseen outcomes along the way.

“I vividly remember my daughter being very young and me sitting on the side of the pool trying to engage in her swimming lesson — and be on a conference call at the same time,” says Pauline Yau, whose career as a technology consultant spans multinationals, start-ups, and a variety of working arrangements.

She has also launched a podcast series, The Flexible Movement, which explores pitfalls and successes of working flexibly. One of the obvious traps is that “on the day you’re not supposed to be working you end up getting sucked into meetings and calls”, says Ms Yau. “I ended up doing 100 per cent of the role for 80 per cent of the pay.”

Culture matters too, she has found. At one start-up, “I had to give up any desire to progress my career because there was no way I could have moved into . . . a more senior role, because I was the only one working part-time and people wouldn’t have entertained that.”

In 2012, Ms Yau joined tech group Microsoft as a full-time employee, working from home one day a week. “It ended up like some form of torture because it was back-to-back conference calls. This was not flexibility,” she says.

Ultimately, her solution was to leave in 2016 to set up as a consultant. “The only way I was going to achieve the flexibility I really wanted was to work for myself,” she says.

Ms Yau’s decision highlights the need for employers who want to retain and attract women to assess how flexible working operates in practice.

“There is evidence that people who are working part-time and flexibly can be among the most productive people in an organisation,” says Jane van Zyl, chief executive of UK work-life balance charity Working Families. Yet, according to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development’s Megatrends report, published in January, the proportion of UK employees working flexibly has hovered around 45 per cent since 2011.

One obstacle to uptake, says Gretchen Spreitzer, professor of management at the University of Michigan, is that some companies allow norms based on habit to develop. “If there is an unintentional culture that is around face-time or about having rigid norms about the way work should get done, that is really unhealthy for everybody,” she says.

Then there is the loyalty that a woman feels towards her employer after she has negotiated flexible working, which can mean she gets stuck in a role, is overly accommodating on how much work she takes on and is unwilling to complain. “It keeps them doing jobs they could do with their eyes shut,” says Karen Mattison, joint chief executive of Timewise, a flexible working consultancy in the UK.

Setting clear parameters helps flexible arrangements work for both sides. Sarah Thwaites, a label head at Sony Music Entertainment UK, has worked four days a week for the past 18 months in order to spend more time with her daughter. Four months into the new arrangement, she was promoted.

“When you work flexibly you don’t have any other option but to be efficient, prioritise and make the most of your team,” she says. Nevertheless, she had to learn to place boundaries around work. As well as worrying about whether she was devoting enough time to both child and job, she says: “I do feel ‘fear of missing out’. There is always a fear that you are being judged that you are not working as hard as everyone else.”

Margaret Snyder is a senior manager in the audit practice of professional services firm EY in Ohio. She has four children under six years of age and works full-time with flexibility. “Every time I have come back from maternity leave there is always that growing pain of trying to figure out what works for you. It is thinking, am I there at the right times?” she says.

Her strategy is to be ready to have honest conversations with her boss, team and clients about what is important, and exactly when she will be available: “Flexibility only really works when you have open communication with the people you work with.”

Some countries are more used to flexible working than others. Carolanne Minashi, global head of diversity and inclusion at UBS, the Swiss bank, says the highest frequency of part-time work is in its Swiss business. “It’s part of the Swiss culture, which is very embracing of professional mums who want to carry on working but not on a full-time basis.”

According to the OECD, with 27 per cent of employees working part-time, Switzerland is second only to the Netherlands (37 per cent) on the proportion of the population working part-time.

Natascha Lander, director of UBS global visionaries and investor forum, works in Zurich four days a week, including at least one day at home, to spend time with her three children. The arrangement works well, she says, not least because management has encouraged flexible working, and it is the norm for her team, with both her male line managers also working part-time or flexibly.

She and her colleagues have developed practical measures to support flexible working. Ms Lander has regular mini-team meetings that can be dialled into or done by video conference. “We keep each other up to date with what is going on. If ever someone is out for other reasons we can back each other up,” she says, adding: “Trust is important.”

Ms Minashi contrasts the Swiss experience with what she sees in the Hong Kong and Singapore businesses, where few work flexibly. A round-the-clock work culture prevails, especially for employees of western-centred multinationals, who are expected to spend a lot of evening time on business calls.

“Unless the culture moves forward,” she says, “the working styles won’t.”

Do’s and don’ts of flexible working

Pauline Yau launched The Flexible Movement, a podcast series that explores working flexibly. Here are her do’s and don’ts:

For the employee

- Don’t be afraid to ask for flexible working. Be ready to offer some facts about the benefits it will bring

- Let your employer know you are still committed to your career

- If you already work flexibly, set boundaries. It is easy to be dragged into checking emails or attending meetings outside your agreed hours

- Be open about working flexibly: tell people, set boundaries and make sure everyone respects them

For the employer

- Encourage flexible working requests from all groups — be “reason-agnostic”

- If you are a leader who works flexibly, draw attention to it. When you leave early, make sure everyone can see and hear that you are going

- Write job descriptions that show you are open to flexible working. Do not put the onus on candidates to ask for it

- Hiring managers who agree with flexible working is critical. But it also has to be easy for them to enable flexible working to happen

Comments