Squeeze on ‘greenium’ as ESG bond investors demand more value

Simply sign up to the Fund management myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Investors have long been willing to pay a premium for green bonds, rewarding companies or governments that want to clean up their act by giving them lower borrowing costs.

But, amid a boom in the issuance of bonds whose proceeds are earmarked for environmental spending, there are signs that this so-called “greenium” is being eroded.

Moody’s expects $450bn of green bonds to be issued worldwide in 2021, up from around $300bn last year. This should help to alleviate the scarcity that made green debt so prized by a fund management industry keen to show it is investing according to environmental, social and governance criteria.

At the same time, many investors are beginning to question the logic of paying extra for a bond with a “green” label, arguing that there are better ways to incentivise sovereign or corporate borrowers to boost their spending on environmentally friendly projects.

These fund managers say that companies or governments should be rewarded — or penalised — based on their green efforts as a whole, rather than hiving off a small part of their activities and rebadging the debt used to pay for it.

“We always evaluate an issuer in its entirety, not just one bond,” says Madeleine King, co-head of global credit research at Legal & General Investment Management. She argues that it makes little sense to pay a premium for a green bond compared with a normal bond from the same company when the creditworthiness — and the sustainability credentials — of the issuer are the same in either case.

“We would have given up a couple of basis points [of income from the bond] essentially for nothing,” King says.

There are signs that other investors are increasingly thinking along similar lines. Measuring greeniums — the difference in yield between green bonds and ordinary bonds of a similar maturity — is difficult to do precisely, as most green bonds coming to market do not have a conventional peer.

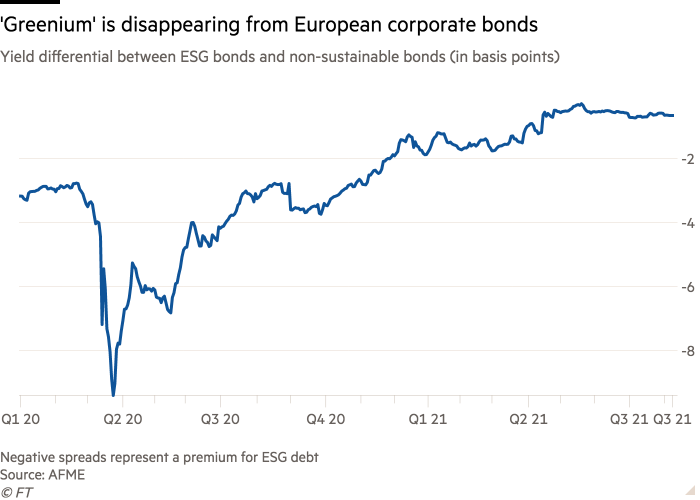

But figures from the Association for Financial Markets in Europe suggest greeniums are shrinking in Europe’s corporate bond market — one of the more advanced markets for green issuance.

Spreads on ESG corporate bonds versus their “non-sustainable” or conventional counterparts have narrowed to less than one basis point — a 100th of a percentage point — in recent months, having climbed as high as nine basis points in 2020.

In sovereign markets, where green debt remains more scarce, these bonds continue to command a premium. The UK’s debut green gilt, for example, last month priced at 2.5 basis points under the equivalent conventional gilt, according to bankers who worked on the deal — saving the Treasury £28m over the life of the £10bn 12-year bond.

According to Stephen Liberatore, head of ESG for global fixed income at US asset manager Nuveen, Europe’s corporate greeniums were driven by the “technical effects” of the European Central Bank’s debt-purchasing programme, and have dissipated as supply increased this year.

In the US market, where green issuance is less established, there has been no persistent greenium in evidence, Liberatore says. He argues that such premiums do not need to exist, given they imply investors should have to face a trade-off between achieving the best returns and funding sustainable companies or projects.

“The main misperception that remains in the ‘responsible investing’ universe is that you must sacrifice performance,” Liberatore says.

Indeed, fund managers point to other advantages of the green bond market besides lower borrowing costs.

King says the process of issuing green debt encourages companies to disclose more information about sustainable practices, helping investors evaluate the ESG credentials of the overall business.

Some bond investors also believe green debt, which tends to change hands less often than conventional debt, will hold up better in a market downturn. “In periods that are more challenging for fixed income markets, green securities tend to [fall less sharply in price],” says Scott Freedman, a portfolio manager at Newton Investment Management. “They have stickier holders.”

Even so, Freedman cautions against buying green bonds indiscriminately, particularly if it means sacrificing performance. “We are not interested in buying a bond for the label,” he says. “We are not mandated by our clients to accept lower returns.”

One alternative to green bonds, championed by investors including Freedman, is so-called sustainability-linked bonds. These bonds do not have their proceeds set aside for any specific purpose. Instead, they penalise the issuer by requiring higher interest payments to investors if the issuer fails to meet certain sustainability targets — such as cutting carbon emissions.

The market for sustainability-linked debt is much younger and smaller than that for green bonds — the first such bond was issued two years ago by Italian energy group Enel — but Freedman argues they are “more powerful” in funding the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Sustainability-linked bonds are also more suitable for the traditionally polluting industries that are trying to make themselves greener, argues King. French oil firm Total, for example, earlier this year committed to issuing only this type of debt.

“Unlike with a green bond, this sets a real target,” King argues. “I think it has the potential to become the standard.”

Comments