Banks betting on Russia face a new test of their appetite

Simply sign up to the European banks myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Western banks are accustomed to political turbulence in Russia. Société Générale, which first set up in the country 150 years ago, was forced to take a 56-year hiatus after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

Since its return, the French lender has navigated the end of communism, Russia’s 1998 sovereign default and the annexation of the Crimean peninsula in 2014.

Now, with Russian troops massing on the Ukrainian border, SocGen was one of the banks put on notice this month by the European Central Bank. The Financial Times revealed this week that the ECB had warned lenders with Russian exposure to prepare themselves for the imposition of international sanctions against the country in the event Ukraine is invaded.

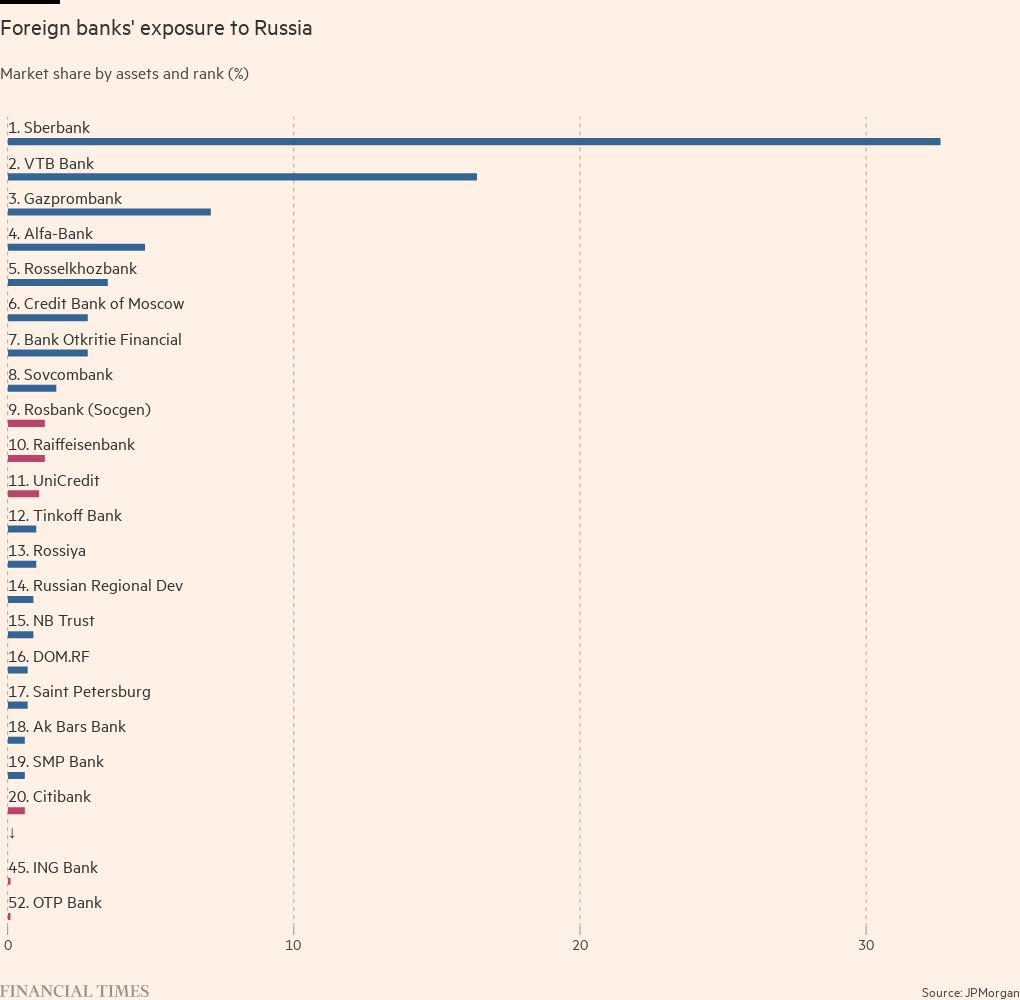

Along with SocGen, Austria’s Raiffeisen Bank and UniCredit of Italy are among the European banks with the most substantial operations. The trio together account for 3.7 per cent of assets in the Russian banking system, according to data compiled by JPMorgan.

Their presence is in contrast to some of the biggest Wall Street banks, including JPMorgan and Bank of America, which substantially reduced their exposure to Russia following the invasion of Crimea.

As a result, the Kremlin has pursued a “Fortress Russia” strategy to make it less reliant on foreign financing. Corporate loans from foreign lenders slumped from $150bn in March 2014 to $80bn last year, according to the Russian central bank.

However, cross-border ties remain significant. Data from the Bank for International Settlements show that international banks, including their Russian subsidiaries, are owed $121bn by Russian entities. Lenders in Italy, France and Austria have the most claims respectively.

For the lenders that have remained, including Hungary’s OTP Bank, the Russian market still has its attractions. Margins on retail banking are appealing, while lucrative trading, financing and advisory fees can be made, particular from the country’s energy and natural resources sector.

Indeed, UniCredit chief executive Andrea Orcel said on Friday that the Italian lender had been examining an acquisition of government-owned Russian lender Otkritie before political tensions over Ukraine escalated.

UniCredit, Italy’s second-largest bank, entered the Russian market in 2005 through a deal to buy Bank Austria, which already had a Moscow-headquartered subsidiary.

Among the information requested by the ECB, was how banks were analysing their Russian exposure and the contingency plans they were readying in the event of sanctions.

Several European banks with operations in Russia said they had been engaging in preparations before the warning from the ECB.

“We don’t need regulators to ask us about how we go about managing risk for us to take action,” the chief executive of one European bank told the FT.

“If you follow the news, clearly you will be looking at your exposures. Whenever there is geopolitical tension and economic uncertainty, you constantly review your portfolio.”

One executive at a European bank with a large Russian subsidiary said it had stepped up its preparations in the past three weeks, significantly increasing its liquidity levels in expectation of anxious customers withdrawing money. It had also tripled the currency hedging on its Russian exposure, they said.

After being badly hit in 2014 when Russia faced penalties over Crimea, the bank had inserted clauses in all its lending agreements in the country so that any clients hit by sanctions would no longer be able to draw additional credit and would have to repay existing loans, the executive said. The bank had also made provisions for potential losses from any sanctions and could hold back further reserves.

Other banks contacted by the FT said they were in “wait-and-see mode” as efforts to resolve the tensions through diplomacy continue.

One US bank that has persevered with Russia is Citigroup, which had $5.5bn in loans, investment securities and other assets tied to Russia at the end of the third quarter of 2021, according to the bank’s most recent 10-Q filing to the Securities and Exchange Commission. That accounted for 0.3 per cent of its total assets.

Last April, Jane Fraser, Citigroup chief executive, said that the bank was putting its retail operations in Russia up for sale, along with those in a dozen other countries. Citi declined to comment.

Although SocGen said it made its first investment in a Russian company in 1872, the bank’s €2.6bn exposure to the country is now mostly through its Rosbank subsidiary. It bought 20 per cent of Rosbank in 2006, taking majority control two years later during the financial crisis.

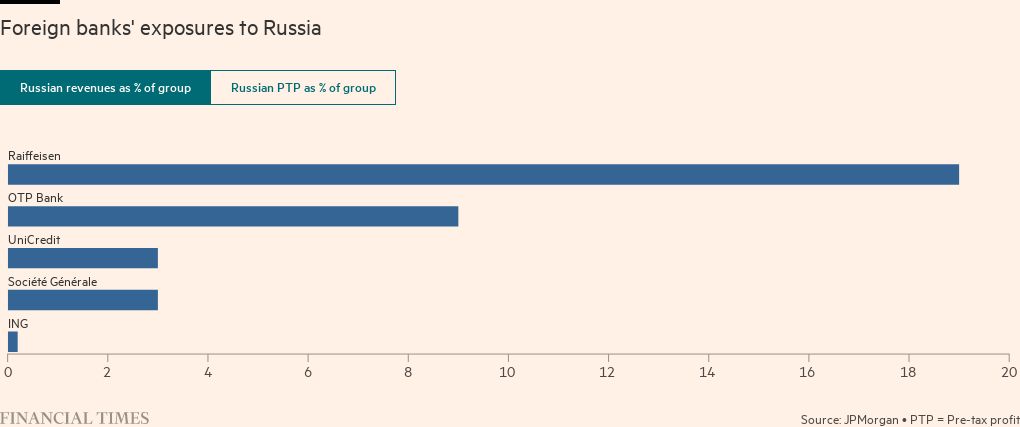

The business accounts for 3 per cent of SocGen’s group revenues and 4 per cent of its pre-tax profit, according to JPMorgan estimates.

“Given SocGen’s exposure to Russia, this has potential to cause higher volatility than the sector on geopolitical developments in the region,” said Azzurra Guelfi, an analyst at Citi.

SocGen played down the risk of its Russian exposure, saying that “Rosbank is operating business in a normal mode within the existing oversight framework”, that “it has mainly local activities” and that the bank is “confident in our ability to ensure the activity for our clients”.

In addition to investment banking services provided at SocGen’s group level, Rosbank operates domestic insurance, car rental, leasing, factoring and receivables arms.

While Raiffeisen has a similar direct exposure to Russia as SocGen, the importance of the country to the Austrian bank’s overall profits is significantly higher. Its Russian operations accounted for 19 per cent of revenues and 35 per cent of the group’s pre-tax profits last year.

Under a worst-case sanctions scenario modelled by analysts at JPMorgan, Raiffeisen would be hit hardest with a 99 basis point fall in its common equity tier one capital, a measure of its financial strength. SocGen would be the second-worst affected foreign bank at 33bp, according to the estimate.

Vienna’s lenders have long had a leading role in banking in central and eastern Europe, acting as a conduit between Russia and the West.

But Raiffeisen only directly entered the Russian market in 2006 with the takeover of Impexbank. The deal was part of Raiffeisen’s wide-ranging expansion in central and eastern Europe over the past three decades.

Over the past year, it has been focusing its Russian and Ukrainian subsidiaries on the largest cities, closing branches in rural and less profitable areas.

Raiffeisen declined to comment.

Additional reporting by Gary Silverman in New York

Comments