A forceful ECB rate rise may fail to curb market tensions

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

On the European Central Bank’s rate-setting governing council sit six executive board members and the 19 governors of the eurozone’s national central banks. I would wager that most of them have read George Orwell’s allegorical fable Animal Farm and its famous line: “All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others.”

At the risk of sounding impertinent, so it is with the ECB. Isabel Schnabel, a board member from Germany, is one of the farm’s more influential voices. Yannis Stournaras, Greece’s governor, though one of the council’s most experienced members, having held office since 2014, has less sway.

So when Schnabel spoke out last month at a central bankers’ get-together in Jackson Hole in favour of forceful action against inflation, markets sat up and listened. They noted similar comments by François Villeroy de Galhau, the powerful French governor. But they attached less weight to a more dovish speech made by Stournaras a few days later at the European Forum Alpbach.

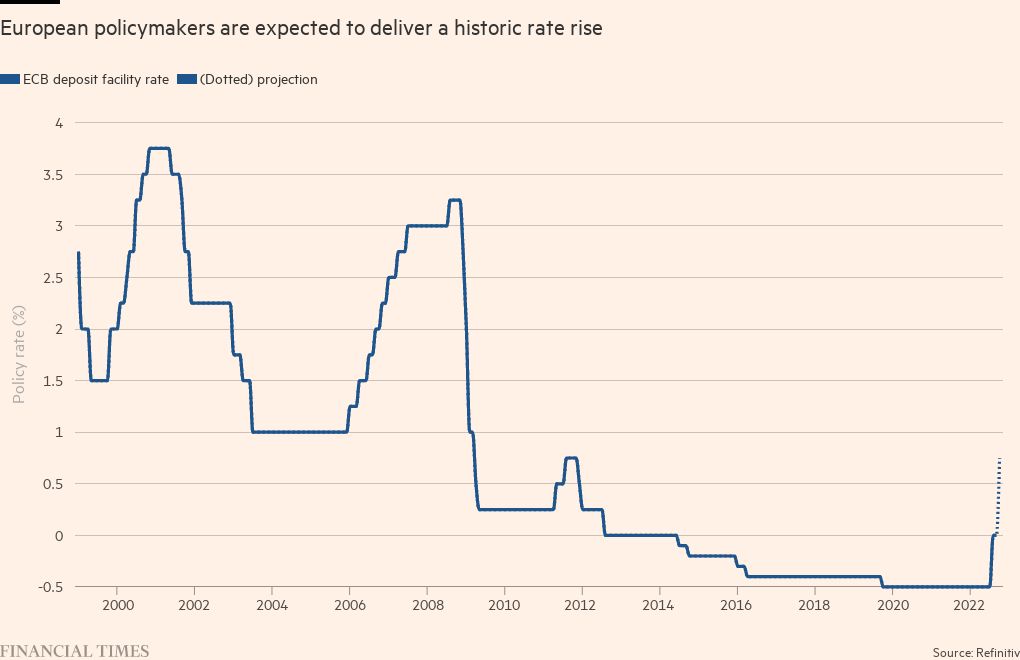

For this reason, the widespread market expectation is that the ECB will raise its main policy rate on Thursday by 0.75 percentage points. That would equal the highest increase in the bank’s 24-year life and would follow a fairly aggressive 0.5 percentage point hike in July.

Does Stournaras advocate a more cautious approach purely because that would be in Greece’s national interest? I’m sure he would say no. Like all ECB council members, he is required to look at the eurozone’s economic outlook as a whole.

Yet financing conditions are starting to vary across the region, and Greece is among those affected. The 10-year Greek government bond yield has risen since late August above 4 per cent, compared with about 1.5 per cent for benchmark German bonds. The Italian yield is close to 4 per cent.

Neither Greece nor Italy is experiencing funding difficulties. We are far from the moment, if it ever comes, when the ECB council might consider activating its Transmission Protection Instrument, its new anti-crisis bond-buying tool.

Under the TPI, the ECB can potentially buy unlimited quantities of one-year to 10-year debt if it judges that financing conditions are becoming fragmented. From a monetary policy perspective, fragmentation means “a sudden break in the relationship between sovereign yields and fundamentals”, Schnabel told a French university audience in June.

Much uncertainty surrounds the legal basis for using TPI as well as the criteria the ECB would apply in deciding whether to act. At a minimum, a country would be eligible for TPI only if it complies with EU fiscal rules, has no severe macroeconomic imbalances and meets conditions attached to the EU’s post-pandemic recovery fund.

Yet disruptive market conditions can arise from various sources. One is a perception that aggressive ECB interest rate rises will damage economic growth prospects in countries with extremely high levels of public debt, such as Greece and Italy.

A second could be a political rupture, such as the expected victory in Italy’s September 25 elections for a rightwing bloc that is signalling it may try to rewrite the terms of access to the EU recovery fund. This would represent a break with the policies of Mario Draghi’s national unity government, which collapsed in July.

A third source of possible disruption is that some investors see high-risk, high-return opportunities in taking positions that gain from widening yield spreads between different euro area government bonds. In an incomplete currency union such as the eurozone, which still lacks a full fiscal, banking and capital markets union, these opportunities exist just as they did when Greece and other countries fell into trouble more than a decade ago.

At the ECB, the prevalent view seems to be that, for the moment, inflation trumps other concerns. The eurozone’s headline annual rate rose to 9.1 per cent last month, and core inflation hit 4.3 per cent. With central bankers worldwide under fire for misjudging inflation risks, the bank may feel a need to defend its reputation with vigorous action.

Yet Stournaras made a fair point when he said there was little evidence so far that rising inflation was spurring a wage-price spiral. For the second quarter, the growth of negotiated wage settlements came in at only 2.1 per cent.

In that light, it may be wise for the ECB, if it raises rates by 0.75 percentage points, to make clear this is an unusual front-loading step aimed at lowering the level at which it finally stops increasing rates, presumably next year.

tony.barber@ft.com

Comments