Designers and dance, the perfect pas de deux

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Stepping inside the costume department at the Royal Opera House in London is like entering a fantasy land – an alternative dimension in the heart of Covent Garden where sugar plum fairies, evil stepmothers and murderous swans all co-exist. Spread across three floors, with a 170-strong team, the wardrobe is a sea of metal clothing racks that look like they should collapse under the weight of gem-encrusted tutus.

Some 20,000 costumes are housed in the ROH’s archive, and thousands are worn by Royal Ballet’s dancers each year. Among them are some of the most iconic costumes of all time: a powder pink tulle confection from The Nutcracker hangs adjacent to a crisp white skirt from the 1832 classic La Sylphide, which is made from 100 metres of netting.

On another rail hangs the rather more minimalist costumes from Christopher Wheeldon’s 2018 production of Corybantic Games – a new ballet dedicated to the late composer Leonard Bernstein. Comprising white ribbon-trimmed brassieres, briefs and translucent pleated tutus, the costumes are the work of London-based designer Erdem Moralioglu, who outfitted the production dancers.

“We won two awards for the collaboration with Erdem,” says Kevin O’Hare, director of the ROH, referring to accolades from the Design Museum and the Walpole British Luxury Awards. It was the first time that the British-Canadian designer, who founded his womenswear label in 2005, had ever costumed men. “It just goes to show that collaborating with people from different artistic industries often has some really magical results.”

Erdem is just one of a growing number of designers to partner with a dance company. The Royal Ballet has worked with Jasper Conran and Gareth Pugh, while Hussein Chalayan costumed a contemporary dance for Sadler’s Wells in 2015. (The company also worked with Alexander McQueen in 2009 and Dries Van Noten in 2017.) Riccardo Tisci created a sheath-like nude gown embroidered with a skeleton for the Paris Opera’s 2013 production of Boléro: worn by both males and females, Tisci – then creative director at Givenchy – had wanted the dancers to appear naked.

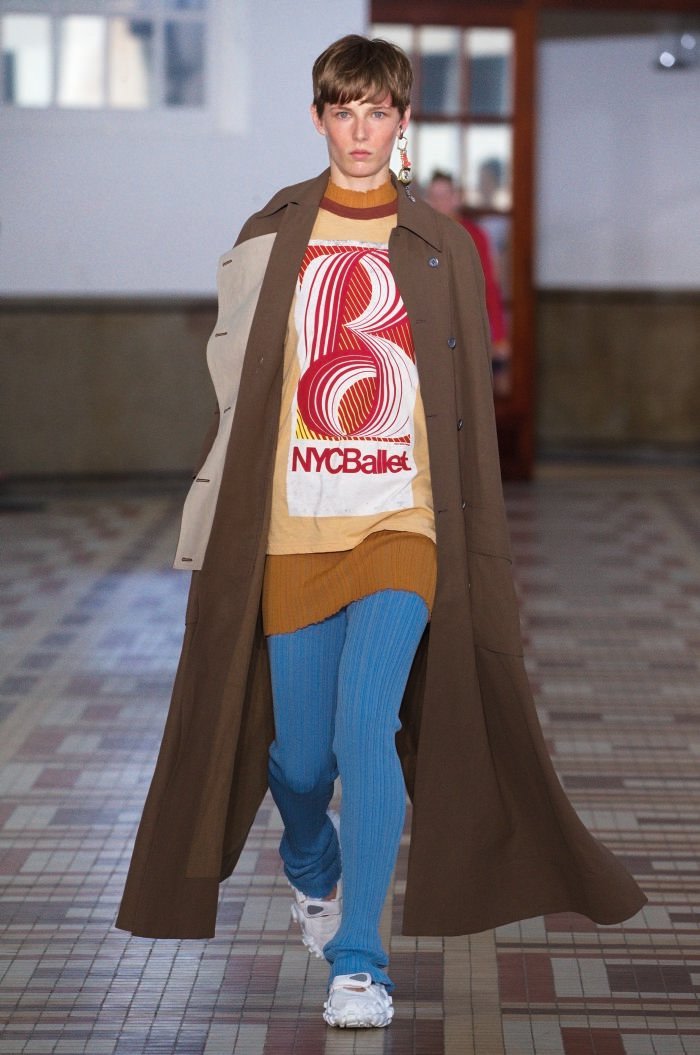

Meanwhile, New York City Ballet’s Fall Fashion Gala has annually since 2011 paired young choreographers with fashion designers on new productions. To date, designers such as Valentino, Virgil Abloh and Gareth Pugh have participated.

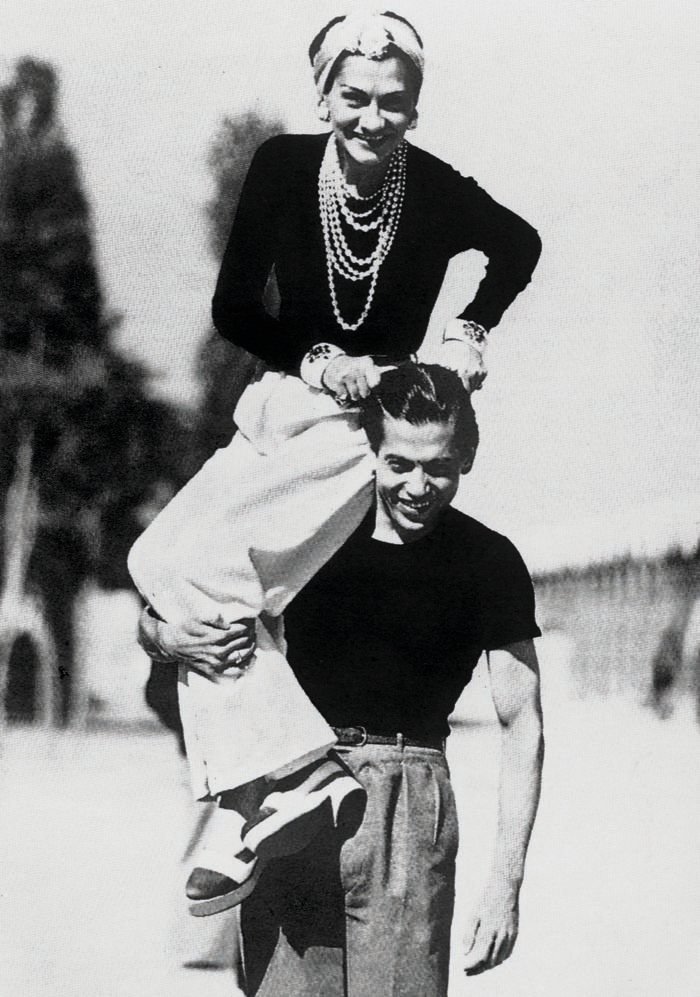

The model is not new – it was pioneered by Sergei Diaghilev’s progressive travelling dance group the Ballet Russes in 1909. Diaghilev, a Russian art patron, commissioned the likes of Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau to design set pieces and costumes, while artist Leon Bakst was a permanent member of the group. “Diaghilev was very much about bringing the worlds together, he was the master of the collaboration format artistic industries utilise today,” says O’Hare. “It was about the music with Stravinsky, the choreographer, the artists. He was the first person to say: ‘We’ve got to think of it as a whole, not just as a dance.’” In 1924, Coco Chanel became the first fashion designer tasked with costuming one of their ballets – she chose knitted bathing suits from her Spring collection.

However, “the Chanel collaboration caused problems for the dancers,” says Valerie Steele, director of the museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York and curator of the 2014 show Dance & Fashion, that explored the enduring relationship between the two art forms. “Her costumes were not designed for the ballet, so when the male ballet dancer would pick up the ballerina, the fabric slid through his fingers – he was at risk of dropping her,” she says. “Chanel hadn’t been thinking about the requirements of dance.”

Designing for the stage has many more considerations than creating clothes to be worn in everyday life, and it’s up to the costume departments to steer a designer in the right direction. “What I have to do is help the designer realise that we’re dressing athletes,” says Marc Happel, director of costumes at New York City Ballet. “They’re going to be jumping around and lying on the floor. They have to be comfortable and not hinder a performance.”

Happel works directly with each designer. His main obstacle every time? Fabrics. “Lots of designers we have worked with, such as Thom Browne or Carolina Herrera or Sarah Burton for McQueen, don’t use a lot of stretch.” Alberta Ferretti – whose romantic, nymph-like aesthetic looks ready-made for the ballet – proposed a costume made from organza. “It would have been a wrinkled mess by the middle of the ballet,” says Happel. “I persuaded her to use a stretch chiffon instead, which is more forgiving. It’s finding ways of convincing the designers to look at fabrics in new ways,” he says.

It’s not just fabrication that proves problematic. “Stage lights kill colour stone dead,” says Jasper Conran, who has worked on 10 ballets: his first, in 1993, was Tombeaux, with Birmingham Royal Ballet’s David Bintley, where Conran redesigned the tutu in a devoré velvet – a Royal Ballet first. “I could be thinking hot pink, but if the lighting designer decides to use an amber hue, that pink is going to turn to mud,” says Conran. “Velvet on the other hand responds well to lighting, it doesn’t lose its lustre. You don’t know what lighting you’re going to have until you’re on stage, so you have to almost guess and manage potential problems with colours before they even happen.”

Before committing to any fabric, Conran takes his textile ideas and looks at them on stage to see how well they cope under the lights – he likens the process to designing something industrial rather than clothing. Moralioglu agrees. “When you’re in the stalls at the back of the ROH, you’re miles away from the stage. The costuming has to translate the narrative to every seat in the house, and it has to really perform,” he says. “It’s almost like a silent film.” It’s for this reason that Moralioglu “desaturated” his costumes, and used a monochromatic palette that was much more stark than his usual collections that are abundant in floral patterns, colours and textures. “It was interesting for me to explore skin,” he adds.

Fashion designers have long been inspired by the ballet in their runway collections – Yves Saint Laurent famously paid tribute to the Ballet Russes in his 1976 couture collection, and labels such as Oscar de la Renta and Acne Studios both drew reference from dance for SS19. It’s understandable, then, that designers are captivated by the idea of designing for the stage. “Dancers are these perfect physical specimens,” says Steele. “Even if a designer is not interested in dance, to see their clothes on ballerinas is an epiphany in how clothes can move.” Alistair Spalding, artistic director and chief executive of Sadler’s Wells, who worked with British designer (and more latterly choreographer) Hussein Chalayan on Gravity Fatigue, agrees. “The dance stage is almost like an animated catwalk. A dancer’s movement can enhance the lines and form of a garment in a way that the catwalk may not,” he says. “They are both primarily a visual media so they sit together very well.”

Many designers have incorporated the theatrics of dance into their runway collections. Dolce & Gabbana’s Alta Moda shows are often illustrated by ballet performances – for their SS15 show, staged in the Scala in Milan, world-famous dancers Roberto Bolle and Beatrice Carbone danced the “Balcony” pas de deux wearing custom bejewelled Dolce. And for his SS14 show, Rick Owens dressed a 40-strong troupe of female stepdancers rather than models – they stampeded down the catwalk during an electrifying 11-minute routine. (The designer returned to dance for his SS15 menswear show, which was inspired by Ballet Russes’ L’Après-Midi d’un Faune.)

This season, Dior’s Maria Grazia Chiuri turned the venue for her SS19 show into a live stage. Held at the Hippodrome in Paris, the show opened with a female contemporary dance troupe dressed in painted Dior tightsuits slinking and stalking the amphitheatre, weaving in and out of models who were dressed in a collection inspired by dance. “Performers wear so many different layers, both lightweight and heavy, so they can add or remove clothing depending on the situation,” she says. “I focused on these garments – leotards, undershirts, coveralls, crossovers and mesh jackets – using various levels to create relations between tones and materials.”

Christian Dior himself was inspired by the ballet. In 1949, he paid homage to Odile in Swan Lake with a strapless black ball gown that was titled “Cygne Noir” – Black Swan. His enduring relationship with dance has been a reference point for many of the maison’s designers – in AW15 Raf Simons looked to Bakst’s exotic Ballet Russes costumes in colourful catsuits while, for AW05 couture, John Galliano was inspired by the dancers depicted in Degas’ 19th century paintings.

Chiuri, too, loves dance. She describes seeing her first production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1980 as “dazzling”. And like Mr Dior (who outfitted Roland Petit’s ballet Les Treize Danses in 1947), she has dabbled in designing for the stage – she created Grecian tulle gowns in siren red for New York City Ballet in 2012 during her tenure at Valentino.

But what’s in it for the ballet companies? “They push me to think outside of our box,” says Happel. “Iris van Herpen introduced us to digital printing,” he says. “Costuming can sometimes feel so antiquated, but here I felt like we really moved into the 21st century.”

O’Hare agrees. “They bring a sense of daring. Gareth Pugh asked if the dancers could wear masks, and asked why the guys weren’t en pointe. Designers bring a fresh eye and question things we take for granted.” Pugh offers an equally pragmatic answer. “It’s important to push things forwards… There’s no point doing something that’s been done a thousand times before.”

Designer collaborations also draw new audiences. “We do partnerships with brands like Off_White or Marques’Almeida,” says Happel. “It gets attention – we’re seeing a rise in younger people in the audience.” Driving new crowds into the theatres is fundamental in ensuring an art form as traditional as ballet evolves. “We’ve worked with [architect] John Pawson, with [artist] Edmund de Waal,” says O’Hare. “And the art and architecture worlds flocked to us to find out what they were up to.”

O’Hare is standing in the auditorium of the ROH, overseeing dancers in dress rehearsals on stage. “There is something so special about stepping into this world,” he says. “We’ve just finished this building project about opening up the ROH, but it’s relevant artistically as well. We don’t want to be a closed shop, we’re hungry to work with people from many different creative worlds and fashion is just one of them.” He’s soon to dash off upstairs for a meeting with the wardrobe department about another project with Conran. “If you stay completely in your own world, then your world is going to stand still.” The sewing machines in the atelier above, meanwhile, continue to whirr.

Comments