Will the Tory post-election spending cuts get through? I’m unconvinced

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of our Inside Politics newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday.

Good morning. The bad news is that we will all be paying higher taxes for worse public services.

The good news is I had a lovely weekend away in Shropshire.

I know, I know, you’re still thinking about the bad news, aren’t you? Anyway, some more thoughts on that in today’s note.

Inside Politics is edited by Georgina Quach. Follow Stephen on Twitter @stephenkb and please send gossip, thoughts and feedback to insidepolitics@ft.com.

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow

The Office for Budget Responsibility estimates that the UK’s borrowing costs will be £70bn larger than expected by 2026-27, according to an ally of the chancellor Jeremy Hunt. Chris Giles and Seb Payne have the grisly details.

There’s a lively debate about whether it’s useful to talk of a “black hole” or a “fiscal black hole” in the public finances. Over on his blog, Giles Wilkes has an excellent summary of that debate, as does Duncan Weldon in his Value Added newsletter. But in many ways, the “black hole” that matters isn’t in the UK’s public finances. You can make that black hole vanish or expand depending on what fiscal rules the government of the day has and by moving the timetable one way or another.

The hole that matters is in the UK’s credibility with the markets. This is the hole that Liz Truss created, and is currently being plugged by Rishi Sunak’s personal brand and Jeremy Hunt’s pleasant speaking voice.

I’m not going to pretend that I know whether an Autumn Statement that promises sharp tax increases in the present day — albeit most of them through frozen thresholds and other tricks — real-terms spending cuts thanks to inflation in the here-and-now, and sharp cuts in nominal spending after the next election will be enough to fix that particular hole.

But what I can say with confidence is that there is no prospect of the UK government ever actually passing those sharp spending cuts after the next election.

Now, of course, there’s a possibility that won’t matter, because instead of a Conservative government we will have a Labour government. A Labour government, I am convinced, will break most of its promises on tax and will implement some sharp across-the-board tax increases and will put the UK on a fiscally sustainable pathway through that route.

But let’s imagine for a moment that the Conservative party manages to turn around its political woes at least a bit, that the fear of Labour tax rises means we end up with either a Labour government with a small or non-existent majority, or a Conservative government with a small majority.

If I were Rishi Sunak or Jeremy Hunt, my concern with delivering a “tax rises now, spending cuts at some point in the future” is that either those spending cuts fail to convince people in the here and now, or the Conservatives end up back in government with a smaller majority and a much bigger problem.

Tax does have to be taxing

Now, as I’ve written before, I think that the only politically and socially viable way for the UK government to repair its credibility, keep pace with the expectations of British voters and survive electorally is to deliver a tax-raising budget while avoiding further cuts (in real, not just nominal terms) to public spending.

Fortunately for the sake of variety, Martin Wolf makes a similar argument in his column:

Why will the state tend to grow faster than the economy? First, the economy needs a well-educated and healthy labour force. Second, the services supplied by the state are ones in which it is hard to raise productivity, which tends to make them increasingly expensive. Third, spending on transfers and health will rise with the proportion of the population that is old and infirm.

Finally, higher spending on transfers and essential services is also what voters demand. Taxes will have to rise as a share of GDP. The only alternative is for the state to abandon important obligations or for it to pretend to promise what people expect, while delivering a worsening standard.

I don’t think that the proposed mixture of tax rises and spending cuts which Sunak and Hunt are flirting with can work for these reasons. But I’m dubious that Labour’s proposed approach of avoiding income tax — and, implicitly, taxes that most “regular” people will notice — can work either.

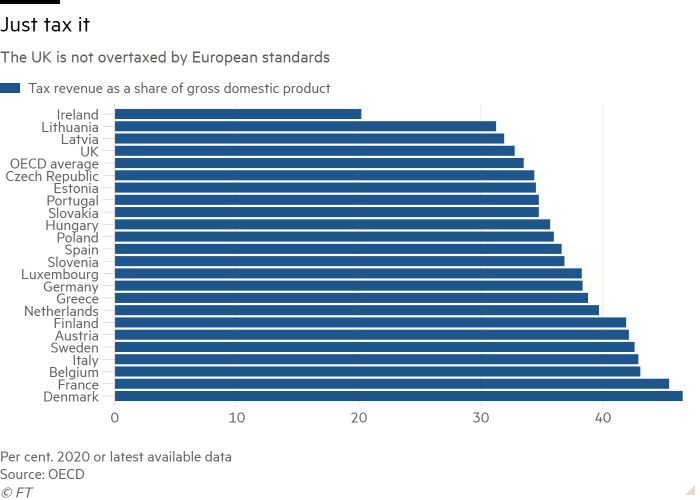

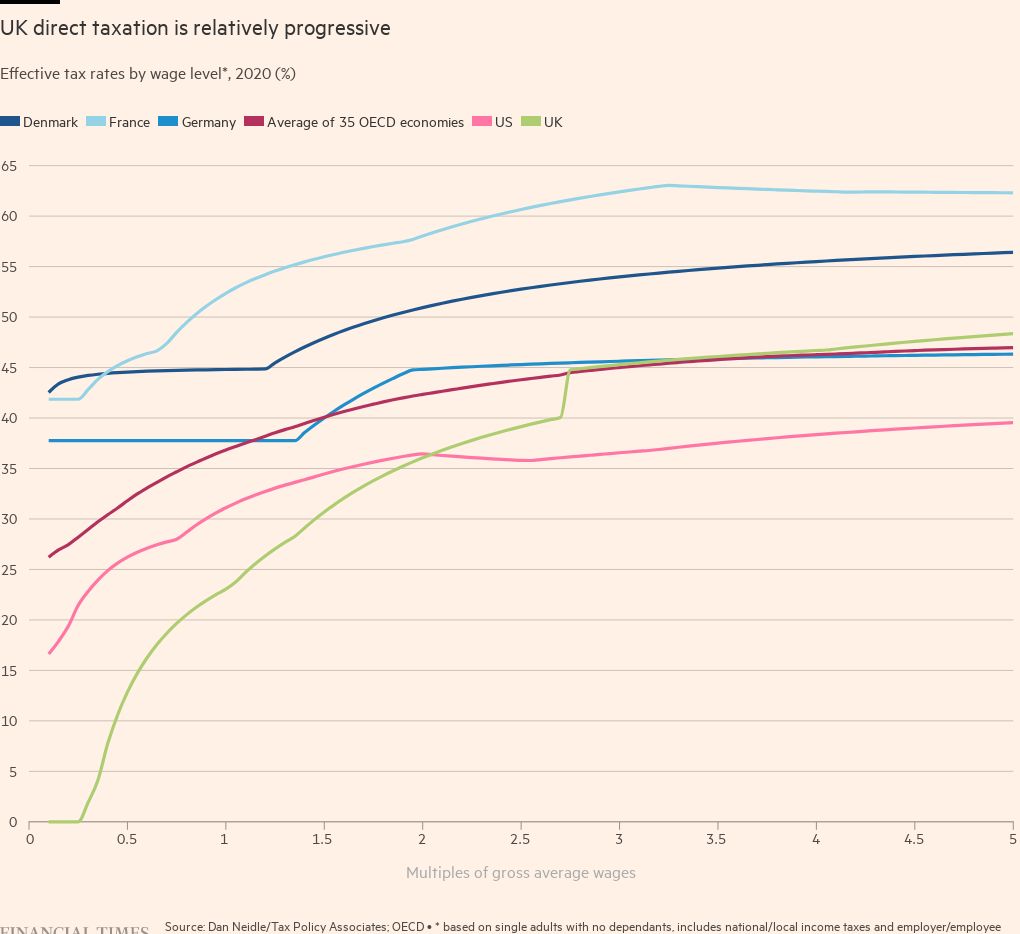

As you can see, the UK’s tax system is already pretty progressive by international standards — it is more progressive, in fact, than the OECD average. I don’t think we can see this as wholly separate from another fact about the UK tax burden, which is that it is comparatively low by international standards.

I’m aware that this is an unpopular position and there are good political reasons why Jeremy Hunt and successive Conservative chancellors have talked about making the “broadest shoulders” bear the heaviest burden.

That was the very successful one-two of George Osborne’s budgets: sharp cuts to public spending (which almost by definition fall heaviest on the poorest and those most in need of state services) coupled by measures that, whether superficially or in some cases significantly, hit the top income decile to make the overall package look “progressive”. But if you want to unpick some of the choices made from 2010 to 2016 on spending you also need to unpack those choices on tax. While some of David Cameron and George Osborne’s measures involved taxes on the rich, some of them involved taxes that most people notice.

Now try this

I was very dubious about the Jackfield Tile Museum (a whole museum just about tiles?) and largely visited it on the grounds that I enjoy the walk from Much Wenlock to Ironbridge and we might as well do something while we were there. I’m pleased to report that I couldn’t have been more wrong. It’s a really lovely museum that is well worth a visit.

Top stories today

Done deal | The UK and France are poised to unveil an expanded migration deal that will seek to curb the growing number of asylum seekers coming to Britain by crossing the English Channel in small boats, according to officials.

Levelling up left behind? | Local leaders are increasingly questioning how much of the levelling up agenda will ever materialise, as high inflation undermines spending on big construction projects. “There’s just loads of problems getting money out the door,” said one government official, adding that the levelling up department was falling behind on spending its budget.

Headroom headache | At the time of its last set of forecasts in March, the OBR predicted the government would be able to stabilise public debt as a share of gross domestic product by 2024-25 with almost £30bn of fiscal headroom. But much has gone wrong since then, as Chris Giles explains in his explainer on what to watch out for on November 17.

Bolton hospital braces for zero capacity | Last month Bolton hospital was forced to declare a “critical incident” after being overwhelmed with “excessive” numbers of patients waiting in accident and emergency, according to Tyrone Roberts, chief nurse. Bolton is working hard to cut its backlogs but workforce shortages loom large.

Peer pressure | The British government should introduce a new corporate criminal offence to ensure that Big Tech platforms and telecoms companies tackle financial crime, peers have urged.

Hunt’s plan | In an interview with the Sunday Times, the chancellor warned: “I’m Scrooge who’s going to do things that make sure Christmas is never cancelled.” Ahead of Thursday’s budget, the chancellor says inflation is “evil”, hard choices have to be made and a recession is coming.

Donation hit to democrats | Sam Bankman-Fried stormed on to the US political scene with multimillion-dollar donations that led lawmakers, particularly Democrats, to believe he was ushering in the next generation of donors. But in a matter of days, his business empire collapsed into bankruptcy and the prospect of millions more in donations evaporated.

Comments