Gilbert & George: ‘All the museums now are woke’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

I had expected, walking into the east London studio of artists Gilbert and George, something like a cathedral. After all, their work over the past five decades has repurposed the bright medieval aesthetics of stained-glass windows for photo-collages of modern urban life, their icons everything from skinheads and bus shelters to sex workers and shit. Although there is nothing numinous about their studio, they don’t disappoint on the icon front: the first thing I see is a white wall covered in photographs, printed or torn from newspapers, of everyone from the Queen to burly rugby players via chancellor Rishi Sunak (several appearances).

“It’s our wall of pin-ups,” says George Passmore, 79.

The medieval is not a comparison the duo, who have been inseparable partners since they met at St Martin’s School of Art in London in 1967, acknowledge, nor any other tradition. “We are not going down that road,” says Gilbert Prousch, 78. “All modern life is more like our pictures, no? If you go to a Tesco, all the design is more like ours, don’t you think?”

“Young people say it’s more like Space Invaders,” says George.

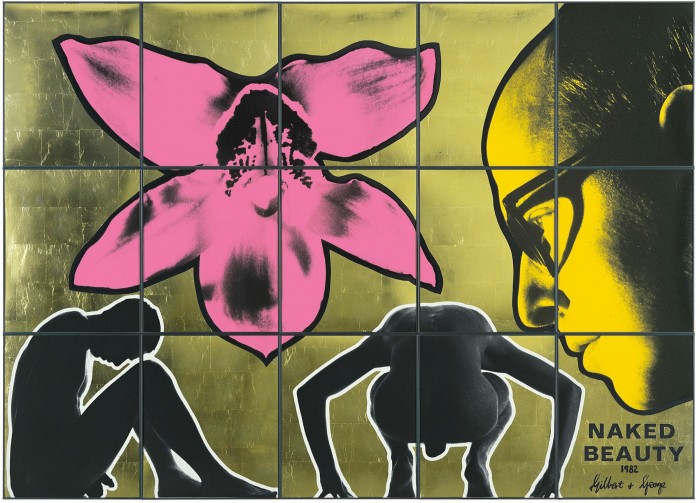

We are meeting to discuss a moment of their career which is slightly closer to Space Invaders than the medieval era: Gilbert and George featured in the 1982 edition of prestigious five-yearly art show documenta in Kassel, Germany, and the Thaddaeus Ropac gallery will be showing works by them and other artists from documenta 7 at Frieze Masters next week. In “Street Meet” (1982), a green young man poses a little like Saint Sebastian in front of a black and white urban scene, while a yellow Gilbert and George stand stiffly like visitors from another planet.

They don’t seem inclined to dwell on that show, though, beyond Gilbert saying it was “very important” and “extraordinary” for them, without too much elaboration. George is keen to stress the freedom, humanism and recognisable signs of their work as a whole: “We realised as baby artists leaving St Martin’s that [fellow students] all did nice shapes and nice colours and nice angles; they never discussed life or hope or death or sex or beauty or unhappiness or dread or fear, never.”

Their conversation is antiphonal, one picking up where the other leaves off. Gilbert follows George: “They all have formalism — forms — and we never had that, from the first day. We only have . . . the humanism of a person, the centre of our art is that. The individual today, how he walks through life. That became our subject and it was quite different, I still believe it’s quite different from many other artists.” Their later pictures have included the artists splayed in bus shelters, newspaper headline posters (they stole 3,700 bills in London for inspiration) and arrangements of postcards featuring the British flag.

Gilbert and George are keen to stress their difference from the attitudes and practices of other artists. For one thing, they dress in identical formal clothes. George today is in a speckled orange suit, white shirt and hot-pink tie with blue crows, Gilbert is in the same suit but green and the same tie but blue. Similarly, they don’t hold with much of the art world’s politics, as becomes clear when I ask about the gallery they are setting-up off nearby Brick Lane to show their work (“the World of Gilbert & George”, as they call it) in perpetuity. Are they doing it because they don’t think other galleries, such as Tate, will convey posterity on them?

Gilbert says: “They have 23 [of our] pieces that they never show . . . All the museums now are woke.” Woke? “Yes.” And you’re not woke? George: “We were woke before woke.” Gilbert: “No, we don’t know what it is, we are normal.”

Why does “wokeness” exclude Gilbert & George, pioneering queer artists? Gilbert: “Because at the moment it’s all black art, all women art, all this art and that art. Just go and have a look at Tate Modern, I’m sure they don’t have a [Francis] Bacon up.” And don’t even mention Tate Britain, where mainly British artists are shown, which Gilbert calls “provincial” and George absurdly compares to apartheid in South Africa. This is definitely different from other artists. It also chimes oddly with their long-held philosophy of “art for all”, which doesn’t seem to stretch to art by all.

They seem otherwise sincere about their vision of art for all. Gilbert: “We feel many times that people cannot have anything, all these artworks that are too expensive for everybody except the rich, but normal people cannot have anything.”

But you’re represented by White Cube, purveyors of art to the rich.

Gilbert: “We have to sell artworks to continue. We like, what do you call it, capitalism.”

George: “We’re not anti-anything, like all the artists normally are.”

Gilbert: “They want to be billionaires but at the same time they say they are socialists.”

(George later adds: “We’re very socialistic but we would never say we were socialists.”)

I ask whether it would be possible for an art student to move to London today, as South Tyrolean Gilbert and Plymouth-born George did in the 1960s, and survive at college then make a career, given the high cost of living, post-Brexit visa difficulties and government cuts to the funding of arts courses. George doesn’t buy it: “We would do the same thing, find the only place we could afford to live. We’re only here because it was the cheapest place in London, that’s the only reason. It was £12 a month for any floor of any building on Fournier Street, the attic or the basement.” (A house down the street sold for £6m in March 2021; Gilbert and George bought theirs in 1972.)

George points to London’s busy art scene as an advantage for today. “When we were baby artists, there were two galleries in London — there was the Marlborough or the Kasmin and that was it.” Gilbert: “Now there are millions and millions of artists out there.” It is, of course, an art world transformed.

But the city has changed with it, and throughout our conversation I have found it perplexing how Gilbert and George can vaunt their close observation of London — George puts on the table three pieces of string he found on the street after breakfast, fresh material for an artwork — yet also be unaware of the ways many of its inhabitants experience it. Perhaps it is precisely that their local universe consumes their whole vision.

As our conversation winds down, Gilbert and George show me ink signs they have made to be sold in aid of the Serpentine Gallery — NO WAY. KISS ME. FUCK ’EM ALL (“Our general approach to life”, says George) — and show me out through their impeccably restored 18th-century house. I ask to take a photo of them so I can remember what they are wearing; they oblige, standing a little uneasily at the threshold, and it strikes me that, in many ways, the world of Gilbert and George goes not much further than their doorstep.

Comments