String of defaults tests safety net for Chinese bonds

Simply sign up to the Chinese business & finance myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When a state-owned coal company in central China defaulted on a bond worth $152m this month, the slip-up seemed unlikely to send tremors through the world’s second-largest economy.

Prior to the default by Yongcheng Coal and Electricity Holding Group on November 10, only five Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) had failed to pay back bondholders in the first 10 months of 2020, according to Fitch Ratings — consistent with levels in recent years.

But within a fortnight, Tsinghua Unigroup, a high-profile state technology group, would also default. That prompted China’s top financial official, vice-premier Liu He, to warn borrowers that Beijing would take a “zero tolerance” approach to misconduct in financing deals, such as misleading disclosures, or attempts by companies to evade their debts.

The developments have rattled China’s nearly $4tn corporate debt market, of which state-owned enterprises are estimated to account for more than half. In the week after Yongcheng Coal’s default, at least 20 Chinese companies suspended plans for new debt issues totalling Rmb15.5bn ($2.4bn), all citing “recent market turmoil”.

Mr Liu’s warning challenges many investors’ long-held assumption that local governments will always bail out state-owned borrowers. Analysts now fear investors will take a dimmer view of the debt, piling further pressure on borrowers.

“People don’t de-risk because they think they can wait for governments to step in before they have to sell assets,” said Logan Wright, an analyst at research firm Rhodium Group. “But now there’s going to be greater government tolerance for pain.”

The recent defaults are different from those in previous years “because local governments are now being considered a source of risk themselves, rather than a source of stability”, he added.

“The risk is that these events have permanently broken investors’ trust in the blanket support of local SOEs by local governments,” Xiaoxi Zhang and Wei He, analysts at Gavekal, wrote in a research note. “It can be difficult to rebuild such trust once it has been lost.”

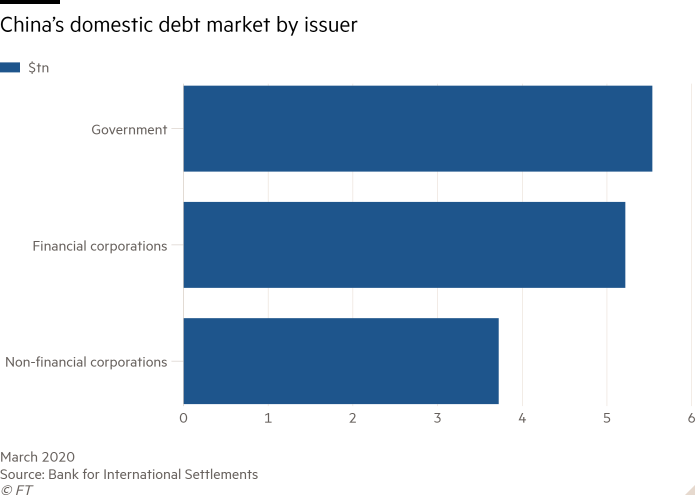

Foreign investors have been increasing their exposure to Chinese bonds, but remain cautious on SOE debt. According to Goldman Sachs, such investors own about 9 per cent of total onshore Chinese central government debt. But they hold less than 1 per cent of the country’s outstanding corporate debt — a market estimated at $3.7tn for non-financial companies, according to the Bank for International Settlements.

If domestic investors were to become similarly wary of local SOEs — which Gavekal estimates account for 60 per cent of all company debt — it could put even more pressure on such firms and their often cash-strapped government owners.

Some workers at Yongcheng Coal say they have not been paid for months, but many investors have been content to ignore warning signs because the parent company is one of Henan province’s largest energy groups and seemed to have plenty of cash on hand.

Huachen Automotive Group, another SOE that defaulted in late October, was also thought to have the backing of its government owner in north-eastern Liaoning province. One of Huachen’s units is BMW’s partner in its successful China manufacturing joint venture.

Yongcheng and Huachen had another thing in common: both companies’ debt was also deemed triple A by big rating agencies.

According to information provider Wind, 70 per cent of all outstanding Chinese corporate and government debt is rated triple A, despite economic stresses caused by Covid-19. While China has weathered the pandemic far better than any other big economy, full-year growth is projected to come in at just under 2 per cent — posing a severe test for companies used to 6 per cent or higher.

Overall credit growth in China has been stable this year, but many regions — Henan and Liaoning included — have been struggling. “When the economy is under pressure, government financial support is limited,” said Shen Meng at Chanson & Co, a Beijing-based investment bank.

“There’s not enough credit flowing through the system as a whole . . . [local governments] are reacting to the fact they have constrained resources as well,” added Rhodium’s Mr Wright.

The defaults have underlined concerns around investor disclosure. In the immediate aftermath, a Yongcheng Coal executive told creditors that most of its cash was tied up in “restricted” deposits. Huachen in September transferred its shares in BMW’s JV partner to a separate subsidiary, which later pledged them to a creditor.

In its statement on Sunday, Mr Liu’s committee warned issuers that authorities would “severely punish” any instances of “false information disclosure [and] malicious asset transfers”.

Yongcheng Coal did not respond to a request for comment. On Monday, a Huachen subsidiary said in a statement that its parent was being investigated by China’s securities regulator for “alleged violations of information disclosure laws”.

Investors are waiting to see how far regulators are prepared to bear down on the market, given the risk of repercussions for the wider financial system.

Chinese officials “recognise there’s no lending discipline in the market”, said Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University. “Right now is probably not the time to test what would happen if there were real, serious defaults and losses taken. But eventually they have to do it.”

Additional reporting by Sherry Fei Ju in Beijing

Comments