ETF backers declare victory after ‘largest ever stress test’

Simply sign up to the Exchange traded funds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When Michael Burry, the doctor-turned-hedge fund manager immortalised in The Big Short for predicting the subprime crisis of 2008, started warning last year about a new financial bubble, people naturally took note.

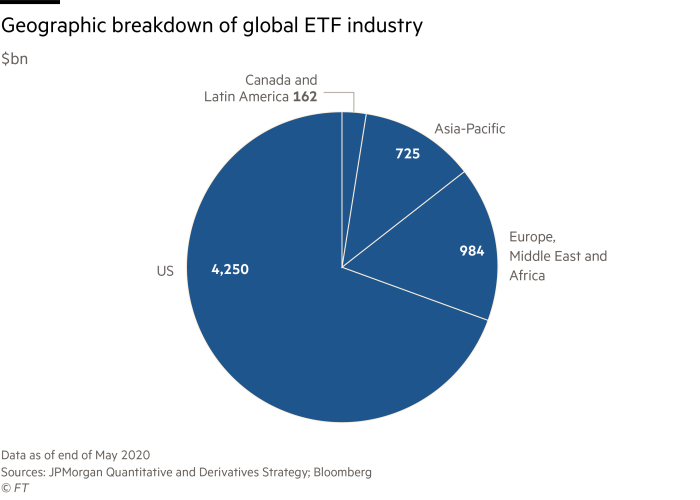

His target this time was the fast-expanding industry of exchange traded funds, investment vehicles that can be traded like a stock but passively track a range of underlying assets. The ETF sector vaulted over the $6tn-in-assets mark last year, up more than sevenfold since 2007. Mr Burry told Bloomberg that ETFs were distorting asset prices, adding: “Like most bubbles, the longer it goes on, the worse the crash will be.”

Many big names in finance have over the past decade warned of the dangers posed by the ETF industry — especially in areas such as bonds — and the role it will play in the next crisis. “What may have been a clever idea in its infancy has grown into a blob which is destructive to the growth-creating and consensus-building prospects of free-market capitalism,” Paul Singer of Elliott Management warned in 2017.

But when a violent sell-off came this year, triggered by the coronavirus pandemic, equity and bond ETFs arguably came through with strengthened credentials — an experience that promises to further embed them into the workings of the capital markets. It was left to a smattering of commodity-linked funds to demonstrate the risks of placing certain securities in the investment structure.

“Any time you see ETFs go through stressed markets you get to see where the stretched seams are and where they might burst,” said Ben Johnson, head of ETF research at Morningstar. Overall, the postmortem was positive, he argued. “The broader ecosystem didn’t break despite a torrent of trading volumes.”

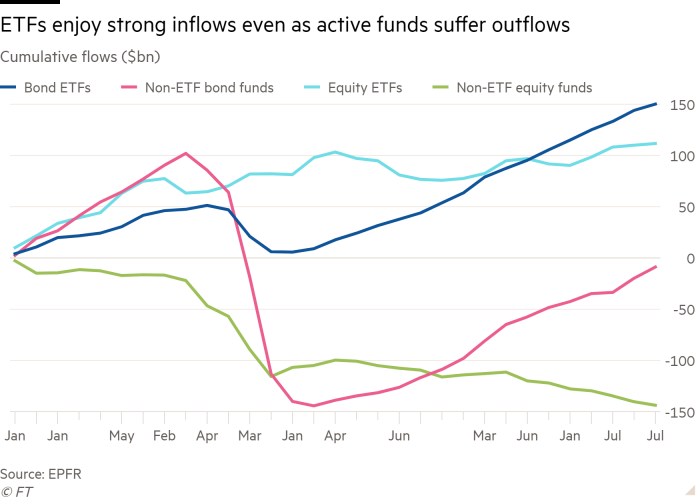

Investors seem to agree. While traditional actively managed equity funds have suffered another $143bn of withdrawals this year, equity ETFs have taken in another $111bn, according to EPFR, a data provider.

The story is similar in the bond market. Despite a strong bounce in investor inflows in recent months, bond funds have had net investor outflows of nearly $9bn this year, while bond ETFs have enjoyed net inflows of $150bn.

Such an outcome would have shocked many at the worst of the market mayhem in March, when the price of many big bond ETFs became detached from the net asset value of the bonds they contain. This sparked fears that investors could lose faith in the product, dump them and trigger a fire sale that spread into wider financial disruption.

Industry executives say the dislocations were largely because the superior liquidity of ETFs meant that many fund managers seeking to raise cash in the panic dumped them, rather than the nearly-untradeable underlying bonds.

Sceptics, however, argued that only the Federal Reserve’s massive interventions, including a promise to buy bond ETFs, helped prevent a calamity and restore investor appetite for the funds.

Nonetheless, many investors were reassured. Alexander Blostein, an analyst at Goldman Sachs, noted BlackRock — the biggest ETF provider — has reported that a third of its fixed-income ETF inflows in the second quarter came from first-time users.

“We believe the resiliency of the ETF ecosystem amid significant market strain in March 2020 underscores its robustness,” Mr Blostein wrote in a note. This “proof of concept”, he said, should draw more first-time buyers to ETFs, helping the product to grow its market share.

However, the Covid tumult did reveal the weaknesses of some products. The ETF structure is essentially a warehouse that providers have used to hold an increasing range of financial securities. Some of them were hit hard.

A good example is United States Oil, which buys futures tied to the price of West Texas Intermediate, the US crude oil benchmark. USO was whiplashed by the plunge in energy prices from March, and its size and influence on short-term oil futures meant that it contributed to sending WTI plunging below zero in April, analysts said. The fund has subsequently changed its approach to mimicking WTI, but several law firms are exploring class-action lawsuits by investors affected by the turmoil.

USCF, the company that manages USO, did not reply to a request for comment.

Many “leveraged” ETFs — which magnify the fall and gain in prices — were also pummeled in the wider first-quarter turbulence, with JPMorgan estimating that about 44 have been closed. Since then, Credit Suisse has announced plans to kill off another nine it manages, which allowed investors to multiply bets on gold, silver, natural gas prices and US stock volatility.

Nonetheless, Marko Kolanovic, head of quantitative strategy at JPMorgan, argued the March tumult demonstrated the ETF industry was not the “ticking bomb” that some critics had argued.

Already, more than $1tn is held in bond ETFs, and many analysts expect that sum to grow significantly in the coming decade, as the fixed-income market is further swept up in the passive investing trend that has reshaped the equity market.

The Covid-19 “crisis provided the largest ever stress test for ETF markets,” Mr Kolanovic noted in JPMorgan’s annual review of the industry. “Other than a few glitches, ETF markets generally functioned as intended and held up well in this stress environment.”

Comments