Zeitz Mocaa boss Koyo Kouoh: ‘We are building our own voice, our own language’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In a reclaimed grain silo on the Cape Town waterfront, Congolese nightclubbers jostle with Xhosa beer drinkers, Haitian schoolgirls, African-American workers and Zulu spiritual healers — all figures in a landmark exhibition at Africa’s biggest contemporary art collection.

When We See Us, a survey of figurative art spanning works by more than 150 artists who have explored black identities over the past century, is a strong statement about the renewed pan-African ambitions of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Mocaa) under Koyo Kouoh, one of Africa’s most influential curators.

“I am a fundamental pan-Africanist — I belong to the entire continent and the entire continent belongs to me,” Cameroon-born Kouoh says of the curatorial philosophy that is raising the profile of “the Zeitz”, a still-young non-profit that was established in 2017 around the private collection of German philanthropist Jochen Zeitz.

The Harley-Davidson chief executive’s name still looms over the towering, tubey edifice, which is dominated within by a vaulting nine-storey atrium that Thomas Heatherwick, its designer, once likened to a “cellular honeycomb”. It has the challenge of being Africa’s biggest repository of modern art while being based in a deeply unequal country where museum-going is often reserved for a privileged few.

But Kouoh, executive director of the museum, has led a major restructuring in recent years with the aim of fulfilling Zeitz Mocaa’s mandate to be on the frontier of the continent’s art.

“In the last 10 years, there has been a resurgence in figuration — and there has been a frenzy about black figuration,” Kouoh says. “It is fundamental to all kinds of art histories, and it’s not different on the continent.” Even if it is, she adds, “annoying” that western collectors and critics sometimes see this as a new discovery.

“I’m here to serve first and foremost the continent of Africa and its diaspora,” she says. And that diaspora stretches far and wide — “I like to make the joke that America is just another African country, that Brazil is just another African country”. This is reflected in the title of When We See Us, a perspectival flip on When They See Us, Ava DuVernay’s 2019 Netflix series on the falsely accused Central Park Five.

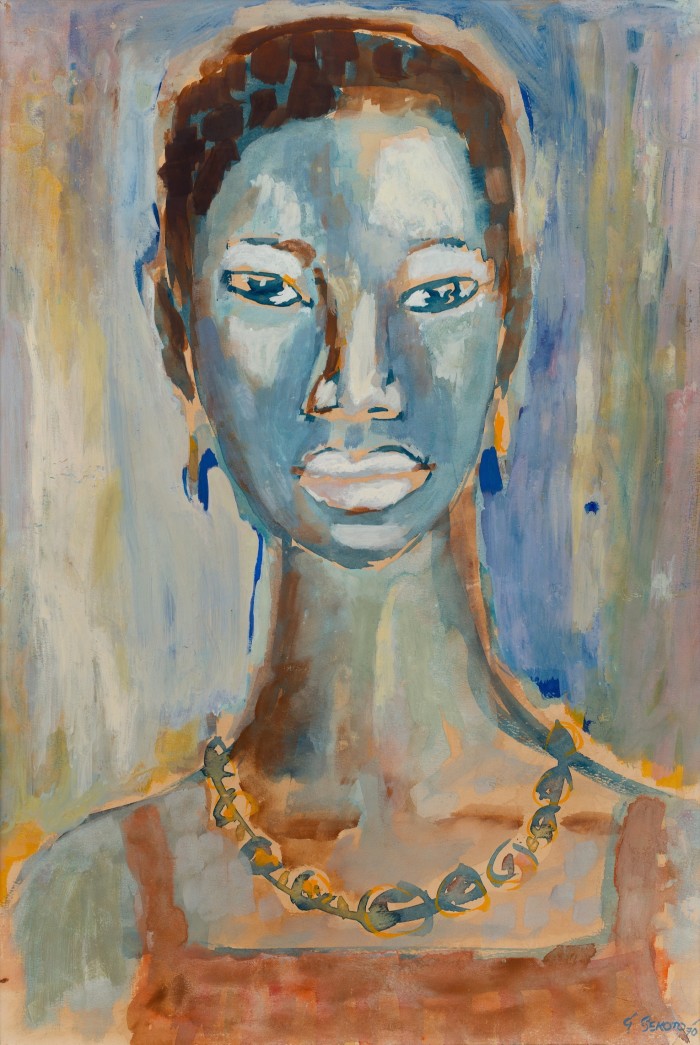

African-American artists such as Kehinde Wiley, naturalistic portraitist of Barack Obama, mingle in the exhibition with major painters in continental traditions such as the South African social realist Gerard Sekoto. Rooms are organised loosely around themes such as daily life and spirituality, rather than chronology or country, forcing these works into dialogue. It is both Kouoh’s trademark and a guide to the future of how contemporary African art might appear on a world stage.

Born in 1967 in Douala and educated in Switzerland, Kouoh moved to Dakar, Senegal’s capital and a centre of arts and culture, in the 1990s. In 2008, she founded RAW Material Company, an independent art space in the city.

“I was one of the first African curators to say that we need to build out independent institutions, to create a genealogy of practice, the history of artistic practice on the continent,” Kouoh says. “The museum is a huge game-changer in the field.”

Even though Zeitz Mocaa is barely five years old, the museum had a shaky start — or, as Kouoh, who was appointed to help lead a turnround, puts it: “We went through multiple crises and came out stronger.”

In 2018, just months after it opened, Mark Coetzee, Kouoh’s predecessor, was suspended for alleged misconduct towards young assistant curators. Coetzee was ultimately sacked, and died last year. The scandal came amid early scepticism about the museum’s governance, academic clout and critical output.

Appointed in 2019, Kouoh made an overhaul of how the museum was run a priority. This had to be carried out at the height of the coronavirus pandemic, with strict lockdowns in South Africa that slashed visitor numbers. “A lot of things have changed,” she says. Zeitz remains co-chair of the museum’s board with David Green, chief executive of the V&A Waterfront, developer of the surrounding harbour district; there is also a “global council” of art-world luminaries such as British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare and lawyer and collector Pulane Kingston, ambassadors for the museum worldwide.

When We See Us is part of the broadening of international clout. “The exhibition is travelling, to Europe and the US,” Kouoh says. Her team is already working on the next exhibition on the same scale, but the museum’s programming will not just group African artists together in big shows.

“The last 30-40 years have been very much imprinted by group exhibitions . . . we needed to reclaim our space in terms of agency and cultural practices, and our ownership of voices,” Kouoh says. The museum will do more to highlight — and look back on — individual African artists with more solo exhibitions and retrospectives, she adds. “From young to mid-career to established, we don’t want to make a distinction. We want a cross-generational conversation between these artists.”

Kouoh is also having to navigate developing a museum with continental ambitions in the midst of South Africa’s post-apartheid political and economic turmoil. Despair is high in the country, which is suffering power cuts and other urgent problems. “I believe in the process of transformation and the process of change, and time is the best ally [for South Africa],” Kouoh says. Before the fall of apartheid in 1994, “we were not even dreaming of South Africa being liberated in the 1990s”.

In a bid to break through the post-apartheid inequality that plagues access to art in the country, Zeitz Mocaa has piloted a “mobile museum” that will tour marginalised townships in Cape Town and further afield. With the University of the Western Cape, a local research institution, Kouoh has also set up a fellowship programme to train a new generation of African art curators.

“It is unapologetically and decisively a pan-African, pan-diasporic museum,” Kouoh says. “I am adamant about it . . . we are building our own voice, our own language.”

Comments