Companies take power into their own hands

Simply sign up to the Renewable energy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Beneath the ground not far from Whyalla, a place where the outback meets the sea, lies the mineral that for decades has fed the dusty south Australian town’s steelworks.

The disused shafts of one old iron ore mine in the area may soon provide another vital ingredient for producing the metal: power.

The owner of the steel plant, GFG Alliance, intends to turn the empty tunnels into a storage facility for pumped hydroelectric storage, as part of an ambitious A$1bn ($722m) plan to harness renewable energy. In doing so, it aims to secure reliable and affordable sources of energy in a region blighted by power problems.

“There was a big blackout not long before we bought the business [in 2017],” explains GFG Alliance chief executive Sanjeev Gupta. “It was almost fatal for the steel plant”.

Other projects include a solar farm and the world’s largest lithium-ion battery, as well as the expansion of a cogeneration power plant, which makes both heat and electricity using waste gas from steel production. Overall, GFG reckons this will save it roughly A$12m a year.

Around the world, manufacturers and other large industrial energy users are increasingly turning towards alternative sources of power to guarantee supply and reduce reliance on traditional power grids.

While many companies in remote areas or with large installations have for decades met some of their own energy needs, the trend appears to be accelerating.

Initiatives range from building small-scale power plants on-site through to deals with energy utilities for direct supply over many years, with renewables often chosen because of their falling costs and the environmental benefits.

“On the one hand, it’s about competitiveness,” says Michiel Cornelissen of the International Federation of Industrial Energy Consumers (Europe). “The other is security of supply . . . Electricity storage will be a very big challenge but also a big opportunity for industry.”

A big push factor in some regions is that heavy manufacturing industries such as steel, chemicals and cement, which consume large amounts of energy, are facing higher bills because of rising costs associated with electricity.

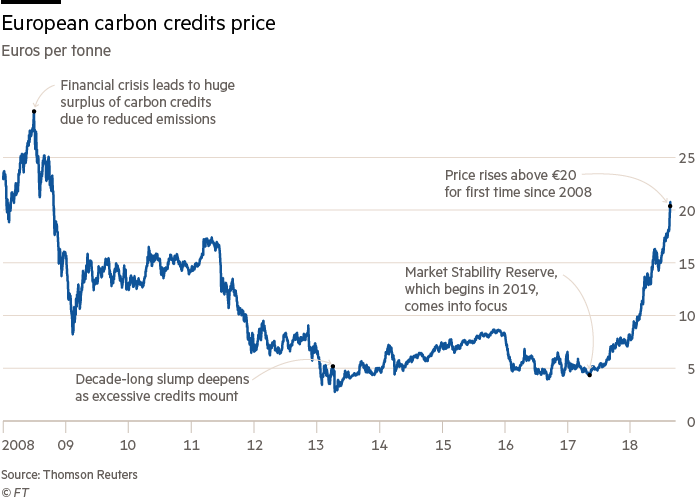

These include charges for the distribution and transmission of power and environmental levies — underlined by the surge in the cost of carbon credits in the EU, which have almost tripled in price this year to the highest level in a decade. Polluting companies must purchase the certificates to cover every tonne of carbon dioxide emitted.

At the Tata Chemicals Europe facilities in northern England, which produce salt and soda ash for glass, the company runs a combined heat and power plant that it acquired from the energy utility Eon in 2013.

It has since reconfigured the plant and added a new turbine, which takes high-pressure steam from heat recovery boilers and reduces its pressure and temperature for use in chemical plants, and in doing so produces electricity.

“We’re classed as an energy intensive group, so CHP [combined heat and power, or cogeneration] is a critical way of keeping a lid on energy costs,” says Peter Houghton, general manager of energy. “They’re very efficient,” he adds. “It’s a big factor for us, so it burns less gas and the carbon footprint is lower.”

Other areas where heavy energy users are taking power into their own hands include water pumping stations and telecommunications, where companies often have good access to land for installing generation equipment.

As well as solving a practical need, “self-generation” also presents a commercial opportunity: excess power produced can bring in additional revenue. GFG believes it could earn about A$80m annually through market sales once its energy portfolio, capable of generating 1,300 gigawatt hours per year, is fully developed.

But there are drawbacks. While renewable sources like wind and solar can remove the need to pay environmental levies, they are also intermittent, says James Morris, an energy expert at PA Consulting.

“[Installing generation assets] also creates the need to manage the infrastructure. There are wires, voltage transformers and substations to be thought about. It’s another contract that needs to be managed,” he adds.

Tata Chemicals Europe says that the investment and maintenance costs for power assets are very high, while it has concerns that new regulatory proposals in the UK could make self-generation unviable in future.

Another way that big energy users — from manufacturers to data centres and science parks — are taking greater control over the cost and nature of their energy supplies is by signing long-term power purchase agreements with utilities.

These “private wire” arrangements bypass the grid and so remove charges for transmission and distribution infrastructure. They typically set prices for energy, giving a high degree of certainty over costs, although it does mean that the consumer is locked in and cannot switch to cheaper power if market prices fall.

Power purchase agreements with renewable generators also enable companies to burnish their ecological credentials as business comes under increasing pressure to join the fight against climate change.

In the Netherlands, a green energy purchasing consortium formed by Google, Philips, Akzo Nobel Specialty Chemicals and nutritional supplement supplier DSM began receiving power from a wind farm this year.

However, experts say that in most instances it is not yet feasible for companies to go completely “off grid” because of their need for back-up supplies from the traditional system.

For industries such as chemicals and paper that often require heat as well as electricity in manufacturing processes, cogeneration from biomass can be preferable as a form of renewable energy.

“It’s a bit easier with biomass, as this is more of a baseload [energy supply] to the extent they have a permanent flow of biofuel, such as waste wood pellets,” says Peter Claes of IFIEC (Europe).

As the cost of batteries drops and their storage capacity increases, many believe there will be even greater scope for companies to make their power through renewables and release it for use in a controlled manner, or at times of peak demand on the grid, thereby avoiding higher electricity prices.

“The concept of having your own generation isn’t new, but it’s taking off and getting smaller,” says Mr Gupta of GFG Alliance. “The future is small power plants and small consumers, more matched in size”.

Comments