Artist Mama Nike: ‘I found a way to make us women powerful, by being able to earn money’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Nike Davies-Okundaye’s headdress is more than 12 inches high, and even the underwhelming medium of Zoom cannot reduce its glory. A tower of black handwoven fabric, it is part headwear, part artwork, embellished with the same red beads that form a stiff collar which sits over her dress. “We make these beads from recycled water bottles,” she says, “then dye them. We take the stuff that litters the rivers and clogs up the gutters and bring it back to life.”

Mama Nike, as Chief Oyenike Monica Davies-Okundaye is most often known, is speaking to me from her five-storey building in Lagos, which she completed in 2008 and which houses an art gallery and a craft shop, as well as a private textile museum and a room dedicated to objects made from recycled plastic and metal. Artists and craftspeople entrust her to sell works in carved stone and wood, brass and copper, alongside embroidered, hand-dyed and -beaded textiles and paintings on canvas. Many of these are by Davies-Okundaye herself.

Davies-Okundaye, 71, is a superstar in her native Nigeria, an artist-cum-activist who has not only ensured the future of the traditional adire textile (an indigo-dyed cloth made traditionally by Yoruba women) but transformed the lives of thousands of women by teaching them the process. This October, kó, a gallery based in Lagos, is bringing her work to Frieze Masters, continuing the trend of textiles, such as quilts by the African-American community in Gee’s Bend, taking their place as artworks. Davies-Okundaye’s work will include batik, patchwork and embroidery. “It is now being recognised as art, not craft,” says Kavita Chellaram, the gallery’s founder. Though really, it is both.

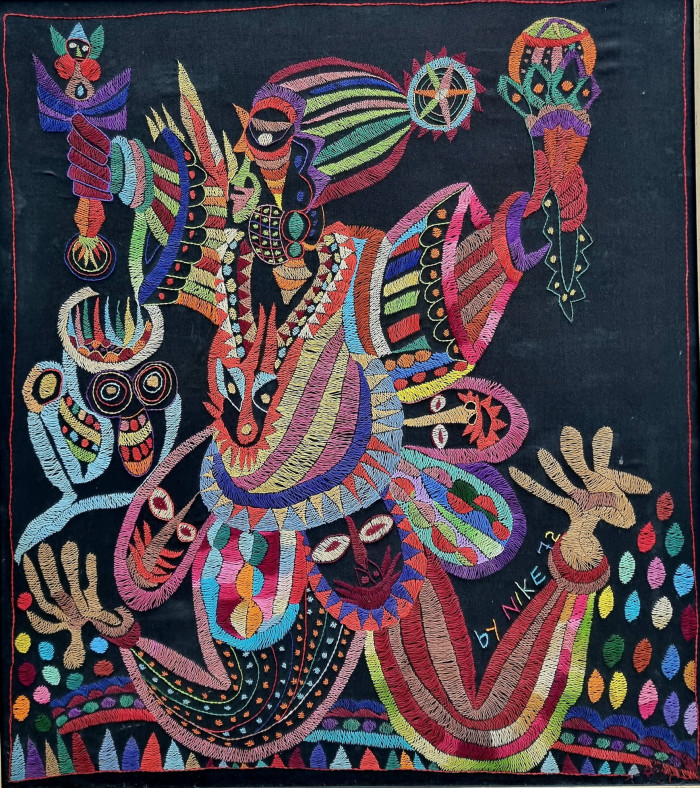

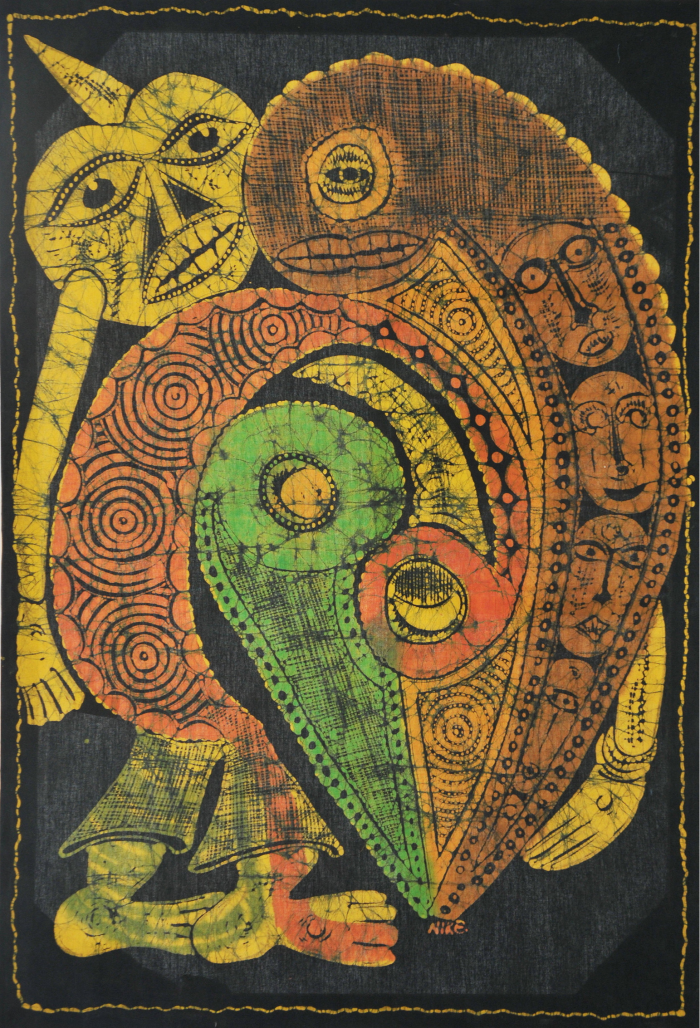

Her works are full of drama and technique. There is a multicoloured embroidery from 1972, an exuberant but fierce depiction of the river goddess Osun in a gown decorated with images of animal heads and masks. A batik work from 1987 shows the goddess as a flattened but still dynamic figure dressed in magenta and indigo blue, her fishtail sliding out from her skirts.

Patchwork, which will also be on show, is a skill she acquired on visits to the US, but has customised with adire textiles. “I first went there in 1974, to Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Maine, to teach the traditional African arts that were dying out,” she says. She tells me that 10 African men had been chosen to fulfil the mission until a group of American women intervened and insisted on the inclusion of at least one woman.

Much of her subject matter derives from the Yoruba religion and the stories handed down for generations of its gods and goddesses. Nigeria gained its independence from the UK in 1960, and Davies-Okundaye is among those determined to keep the country’s spiritual history alive. She deals with contemporary issues too: a beaded work made in 2016 concerns the Chibok schoolgirls abducted in 2014 by terror group Boko Haram. “It is important to talk about what is happening to women,” she says. “I want people to like the colours and the images, but also to think about what I’m doing.”

Davies-Okundaye’s own life story is dramatic. She was born in 1951, in the hill village of Ogidi-Ijumu in Kogi state. Her father embroidered for a living. “He would fully embroider the front and the back of the abada, or robe, for the king,” she says. “And he would work with beads to make his crown. But he was still very poor.” Her mother died when she was six, her grandmother a year later, and Davies-Okundaye went to live with her great-grandmother, where she learnt the art of adire.

This involves making indigo dye by soaking indigo leaves in hollowed-out cocoa shells, then using cassava paste applied to cotton to resist the dye. The process of applying a design to the hand-woven cotton, which comes in five-yard lengths, takes a month to finish. “We paint the designs with feathers,” says Davies-Okundaye, “and make dots using a knife tip. My great-grandmother showed me everything.”

Aged 14, Davies-Okundaye was married by her father to Twins Seven Seven, seven years her senior and a complicated character said to be the only surviving child of seven sets of twins. A dancer and musician and then artist, he eventually took on 15 wives. But Davies-Okundaye had other ideas. “I started using my skills, and by 1967 I had a gallery in my own bedroom,” she says, laughing. With the assistance of other wives, she established a business making and selling adire. “I would have liked a formal education,” she says. “But instead I found a way to make us women powerful, by being able to earn money.”

Liberated from her marriage after 15 years, having had four children, Davies-Okundaye frequently went to Lagos to sell her designs, dressed in her own wearable artworks that made people approach her in the street. She met a Welshman who had lived in Nigeria for 25 years, working on water projects; they married in 1982 and had two daughters, but when he decided to retire to Wales in 2002, she chose not to follow. (“Wales? In the winter?”) Her current husband, a police commissioner who she met in 1992 while being arrested for “inciting feminist tendencies” (in her words) during her workshops, will not be attending the fair. “He’s 88!” she beams. “He wouldn’t be able to cope with the weather.”

Mama Nike has used her craft to bring women with her. Building on the teaching methods that she developed during her first marriage, she set up training camps and workshops in Ogidi-Ijumu, Abuja and Osogbo. “A lot of husbands don’t want their wives to become artists, to have skills,” she says. “But now I have taught around 4,000 women to have their own livelihood. Women have to lift women up. You train a woman, you train a nation.” Another project has focused on sex workers in Italy, where Nigerian men have often sent women to earn money from prostitution. “Someone found me on the internet,” she says, “and took me to Italy to teach textile skills to these women. Then, when they come back they can earn money. Out of the 5,000 we have targeted, we have changed 2,000 lives.”

“Finally there is a younger generation who appreciates both its cultural and technical value,” says Davies-Okundaye, whose work is in the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in Washington, DC. “They come back from being educated in the UK and the US and suddenly they want to look to their origins.” They can find them in the work of Nike Davies-Okundaye.

Comments