‘The market is just dead’: Investors steer clear of 20-year Treasuries

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Investors are shunning 20-year US government bonds, causing a distortion in the $23tn US Treasury market.

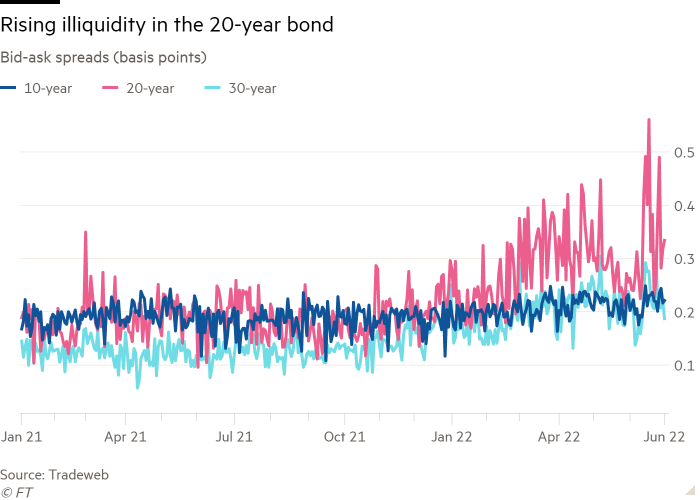

Demand for the 20-year government debt security since its reintroduction in 2020 has been so weak that its price is far out of sync with the rest of the market and it is harder to trade. The price swings and lack of liquidity have made it even less popular with the long-term, conservative investors such as pension funds that would typically be its natural buyers.

“The 20-year part of the market is just dead,” said Edward Al-Hussainy, senior interest rates strategist at Columbia Threadneedle.

The difficulties in drumming up investor demand for 20-year Treasuries could ultimately spread to other parts of a market that act as the bedrock of global finance, said Mark Cabana, head of US rates strategy at Bank of America.

As a result of the lacklustre interest, the 20-year stands out as the cheapest conventional bond within the Treasury market. The low price means yields on 20-year Treasuries are higher than their 30-year counterparts, at 3.37 per cent and 3.1 per cent, respectively. Typically longer-dated bonds provide higher yields to account for the greater risks associated with holding debt that matures further into the future.

Cabana said the higher yields required to convince investors to hold 20-year Treasuries ultimately cost taxpayers by nudging the government’s cost of borrowing higher.

“They discontinued 20s once in the past,” he said. “And why did they discontinue it in the past? Because they felt that it was not advantageous to the taxpayer. It was not achieving the lowest cost of funds for the taxpayer, and that argument can be easily made today.”

The disparity between the 20- and 30-year yields widened earlier this month as the Federal Reserve sharply tightened monetary policy in a bid to counteract soaring inflation. The reduction in the size of the Fed’s $9tn balance sheet has only exacerbated these problems, as the market has been left with more supply to absorb.

The revival of the 20-year bond, which the Treasury had mothballed for more than three decades owing to lacklustre appetite, was part of a broader plan to significantly increase the government’s borrowing through longer-term debt in a bid to lock in lower rates for an extended period of time.

“It just never really got any traction because [the 20-year] has traded so poorly relative to other similar [long-dated] instruments, and the liquidity is terrible,” said Bob Miller, head of US multisector fixed income at BlackRock. “Then you throw on a nine-month period where the Fed has pivoted and is intentionally very aggressively trying to tighten financial conditions . . . [and] that has exacerbated the structural weaknesses that were already evident.”

The 20-year is expected to remain cheap going forward because the amount being issued by the Treasury is so much higher than the demand for the securities. When the Treasury reintroduced the debt in 2020, the first auction was for $20bn, twice the size of what had been recommended by the group of industry representatives — the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee — which advises the Treasury on refinancing.

As pandemic-era fiscal spending has slowed, the Treasury has reduced the size of its 20-year auctions, alongside reductions across other maturities, but in the latest quarter at a slower pace than recommended by the TBAC.

The 20-year is expected to remain out of vogue not just because of the excess supply, but also because of the rise in volatility in the Treasury market as bonds are whipsawed by recession fears and the changing outlook of the Fed. The 20-year typically endures big price swings when markets become volatile because sluggish demand makes it harder to transact.

The low price, volatility and illiquidity have brought in a new crop of investors: hedge funds looking to exploit inefficiencies in the pricing of the 20-year.

“It takes a brave person or someone who has deep pockets to hold on to [a position in the 20-year] for a long time and withstand a lot more volatility,” said John Madziyire, head of US Treasuries at Vanguard.

“That’s why you see hedge funds are the ones who are more likely to try to step in,” said Madziyire, who expects to remain underweight the 20-year because of the firm’s “conservative” approach.

The most active players in the 20-year are hedge funds and the clutch of banks that transact directly with the Treasury, known as primary dealers, according to market participants.

“When you look at the risk you have with the leverage you need to apply to make real returns, it becomes a very, very difficult position for most people to hold in material size,” said a portfolio manager at a large US hedge fund.

On Friday, the Treasury will send out a questionnaire to primary dealers, soliciting feedback on their quarterly refunding process, during which issuance sizes are determined for the three months ahead. Cabana said he would be watching closely for any evidence that the Treasury was prepared to meaningfully cut 20-year auction sizes.

“Treasury basically needs to cut until the [20-year] point stabilises itself, but be open to the notion that there may not be any level of issuance that really is justifiable,” said Cabana.

Comments