Are investment returns from cannabis just a pipe dream?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Selling cannabis might sound an unlikely second career for a currency trader, but when David Burden decided he had tired of the City of London he took a punt on what he thinks is the next big consumer and medicinal trend.

Launching The London Botanists, a food supplement business that sells essential oils containing cannabidiol, a constituent of the plant, Mr Burden hopes to ride a wave powered by the prospect of global liberalisation of cannabis.

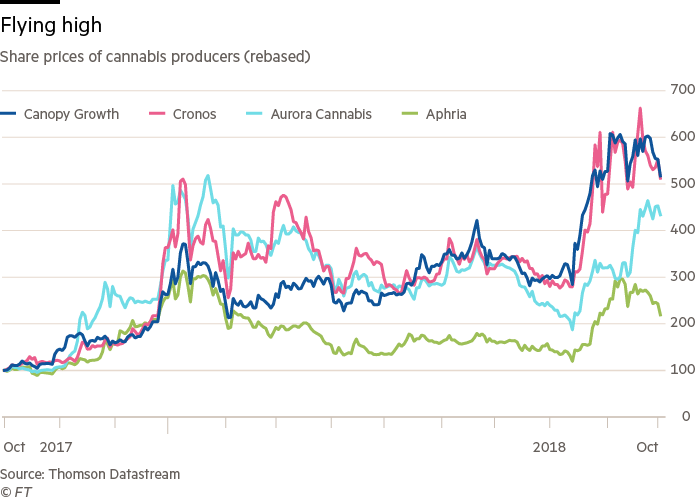

He is not alone. At the vanguard of the industry is a collection of Canadian companies, listed in Toronto, whose share prices have rocketed over the past year as investors have piled in.

Canada plans to legalise the recreational use of cannabis this month, becoming the first developed market to do so on a countrywide basis, though the drug is available for recreational use across nine US states too, including California, Colorado and Massachusetts.

A surge in deals activity among cannabis producers, as well as investments and expressions of interest by major drinks companies, has further fuelled excitement in the market. But with some of the so-called “pot stocks” quadrupling in price over a year, worries have emerged about investment risks in an overheated sector.

“There are undoubtedly some bubble-like signs when you look at the share price rises of some of the companies involved,” says Ed Monk of Fidelity International, the asset manager. “Are they destined to disappoint? There are bound to be some huge successes but the problem for investors is knowing which companies, or even which sectors, will gain most.”

David Stevenson, FT Money’s Adventurous Investor columnist, warns that some of the companies could be “heinously overvalued” as investors pour money into the sector, even if they were “perfectly legitimate” companies.

Cam Battley, chief corporate officer of Aurora, Canada’s second-largest cannabis producer, insists that the plant is a new “global megatrend”. Analysts at BDS Analytics estimate worldwide spending on the drug could hit US$32bn by 2022, a sharp rise from the current $9.5bn.

Is cannabis the Next Big Thing or a bubble waiting to burst? FT Money assesses how investors should respond to the opportunities and risks of a fast-growing industry.

Thinking outside the potbox

Canadian companies have spread their wings as the use of cannabis and its related products have gained greater legitimacy. In July, Tilray became the first cannabis producer to carry out an initial public offering in New York, closing 32 per cent up from its listing price.

Analysts say that while investment is being partly driven by the impending legalisation in Canada, companies were more excited about the potential for the US market.

Investors and analysts break the industry into two parts: medicinal cannabis and consumer products. Those companies promoting cannabis for healthcare claim it can be used to manage symptoms ranging from fibromyalgia to epilepsy.

Although only nine US states allow citizens to smoke marijuana freely, around half of the country’s states have approved the drug for medicinal use, while European countries such as Germany and Denmark have also done so.

Large pharmaceutical groups such as Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline have so far shied away from cannabis, on the grounds that it is unlikely to produce patents or valuable intellectual property.

Mr Battley of Aurora says that although the company does clinical trials, they are smaller than those conducted by the pharma giants. He nonetheless hopes Aurora can succeed in patenting forms of cannabis that are consistently high in some specific cannabinoids and low in others, he says. “What you really need to do is master the agricultural science and supercharge the plant.”

The group is also building high-tech facilities, known as “Aurora Sky” farms, to automate the growing and harvesting process as far as possible and regulate the plants’ environment, protecting them from pests. Its biggest farm is 1.2m sq ft.

In the UK, a smaller group of companies are focusing on the plant’s medicinal uses. Cannabis hit the headlines in the UK this summer when 12-year-old Billy Caldwell had the medicinal cannabis oil used to treat his severe epilepsy confiscated from his mother at Heathrow airport.

His family fought hard for its return, arguing with politicians that it was the only medicine that could control Billy’s seizures. Eventually Sajid Javid, the home secretary, said the medicine could be returned on a temporary basis.

Geremy Thomas, chief executive officer of the London-listed medicinal cannabis company Sativa Investments, says this episode prompted more serious consideration of the drug among UK politicians.

“When I started Sativa, it was all about ‘if’ this happened in the UK,” he says. “Now it’s about when. This stuff works and patients in the UK have been denied access to it, while patients in Germany and the Netherlands have been having it.”

Mr Thomas says the scale of investment into the UK sector is far from matching the sums being poured into cannabis production in North America. “It amazed me, the amount of money flowing into the cannabis business in Canada and the US,” he says. “I don’t think UK investors understand the scale of the business in Canada and the US.”

Despite this, some investment experts believe cannabis companies still face significant struggles. Mr Monk of Fidelity says cannabis “bears comparison” with other farmed commodities. “Producers may have limited pricing power and find themselves competed against by anyone else offering the same thing cheaper.

“They may also face hyper-cautious regulators and political interference.”

Far out: the consumer craze

The second wave of interest in cannabis comes from companies which see the plant as a potential consumer product. Aside from the legal highs available in some US states and Canada, drinks and tobacco companies are looking into how the constituent parts of the cannabis plant could be used to fortify their products.

Canopy Growth Corp, whose Toronto stock exchange ticker is WEED, attracted huge interest this year when Constellation Brands, maker of Corona and Modelo beers, raised its stake in Canopy to 38 per cent with a $4bn investment, the largest so far in the industry.

Last month, Coca-Cola, the world’s largest beverage group by revenue, was reported to be “closely watching” the sector with the aim of developing a drinks range; Canadian company Aurora Cannabis was said to have held talks with the drinks group.

Aurora has been acquisitive, buying up rival medical marijuana group MedReleaf in a $2.5bn deal this summer. The group snapped up CanniMed Therapeutics five months ago and previously invested in the public listing of The Green Organic Dutchman, a cannabis producer. Diageo, the world’s largest distiller, has also held talks with three Canadian cannabis companies over a potential partnership or investment to create drinks.

Proponents argue that the market opportunities are not about getting high, but different flavours, aromas and psychological effects offered by different parts of the cannabis plant. Those in the industry argue that the chemical which produces feelings of euphoria is only one of more than 100 cannabinoids or active compounds in the plant; other constituents offer mellower effects ranging from mild relaxation to reduction of inflammation.

Linda Gilbert, managing director of consumer insights for BDS Analytics, says cannabinoids were already being used in consumer products in some US states where cannabis-infused products are available from licensed dispensaries.

The products available typically range from chocolate truffles to lotions, and even include pet foods. Ms Gilbert describes the dispensaries as “upscale” in appearance, featuring “budtenders” who help customers choose between different brands of cannabis-laced goodies.

Sports drinks are a prime focus of interest for consumer industry companies, says Ms Gilbert. “If there is CBD [cannabidiol] in my sports drink, it might help me relax and I might pay more for that.”

Alex Brooks, analyst at Canaccord Genuity, says the “most interesting” part of the potential market is the “wellness” industry.

“There is a lot of research going into CBD. It’s a product you’ll see in face creams and balms of all kinds, as well as in your local Holland & Barrett.”

But for all the hype, there are dissenting voices too. Mr Stevenson, the FT columnist, warns that “thematic” investing, which tries to take advantage of a broad global trend and invest around that theme, tends to attract a lot of money from specialist passive funds.

Other examples of “thematic” investments include rare earths, where investors bet on the rise of lithium batteries, and blockchain, the digital ledger technology behind bitcoin and ethereum, the cryptocurrencies.

Mr Stevenson says money pouring into passive funds, which automatically buy up the stocks in their index, lead to an “over-allocation of capital” to some of the companies. “There are interesting companies in the mix, but by and large most of them should be avoided,” he says.

For active investors, picking the right companies among a field of new entrants can be tricky. “There’s usually a land rush and everyone piles in,” says Mr Stevenson. “You’ll usually get one or two respectable players, a few sexy versions, and all the rest are rubbish and shouldn’t be touched with a bargepole.”

A piece of the action

For UK investors willing to look beyond such risks, there are at least two UK cannabis manufacturers, Ananda Developments and Sativa Investments, both of which aim to develop medicines and are listed on the UK’s junior Nex market. GW Pharmaceuticals, another British company, was previously listed on Aim but has since relisted in the US.

Although smaller than Canada’s companies, they are poised to take advantage of any move to loosen the rules governing the use of medicinal cannabis in the UK. In July, Mr Javid said cannabis-derived medicines should be reclassified to allow UK doctors to prescribe them.

Another option would be to invest in related companies. Mr Monk of Fidelity says it might be food manufacturers or agricultural property and services that could prove “winners” in the market.

Ms Gilbert agrees: “For investors, the question is: can cannabis makers make as good a drink by infusing it with cannabis as a soft drinks producer could?” She adds: “Natural product brands used to be mom and pop enterprises, but now they’re all owned by the Unilevers and Diageos.”

UK equity fund managers are exploring how the trend might be incorporated into their portfolios. For more conservative fund managers investing in the cannabis-related activities of the soft drink, alcohol and tobacco giants may be a subtler way of gaining exposure to the cannabis boom than direct investments.

One UK equity manager, who did not want to be named as he was in the early stages of researching the industry, suspects the UK is “really behind the curve” and worries that cultural attitudes towards cannabis have held back the industry’s growth.

“Older people believe that anything to do with smoking weed is fundamentally wrong,” he says. He adds, however, that there is potential for a new set of consumer products.

“This feels very much to me like vaping, like the next-generation product in the tobacco sector felt five or six years ago,” he says. “There’s a proliferation of companies going on a land grab to get consumer base, but the reality is that they don’t have the network to develop the potential. Tobacco companies will just let these guys start up and then acquire them,” he says.

For Mr Burden and his partner in London, the success of their UK business relies on importing raw ingredients from wholesalers in Europe, but they hope for more regulation and openness so that smaller business like theirs can grow and attract investors.

“I want to make an organic product and I want it to be mainstream,” he says.

Flying high before the comedown

Tilray, the first cannabis company to carry out an initial public offering in the US, recently reached a market capitalisation of about $20bn.

Although its shares were valued at $17 when it listed on Nasdaq in July, they soon hit $300 on news that the company had received approval from the US Drug Enforcement Administration to carry out a clinical trial on its products in the US.

The company, which is mostly owned by private equity group Privateer, then saw its shares rise by as much as 93 per cent on one day and down by 20 per cent on another. The volatility was blamed on the relatively small number of shares trading freely.

Not everyone was keen to buy the stock. One short seller, Citron Research, described the gyrations in the lossmaking company’s price as “beyond comprehension”.

Comments