German chemicals giant stockpiles coal to keep producing

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A potent sign of Europe’s energy crisis can be found at the Marl Chemical Park in Germany’s industrial heartland of North Rhine-Westphalia. A coal-fired power plant that had been due to close by the end of this year will instead keep running through the winter, and beyond, to provide energy for the companies on the site — helping to maintain more than 10,000 jobs.

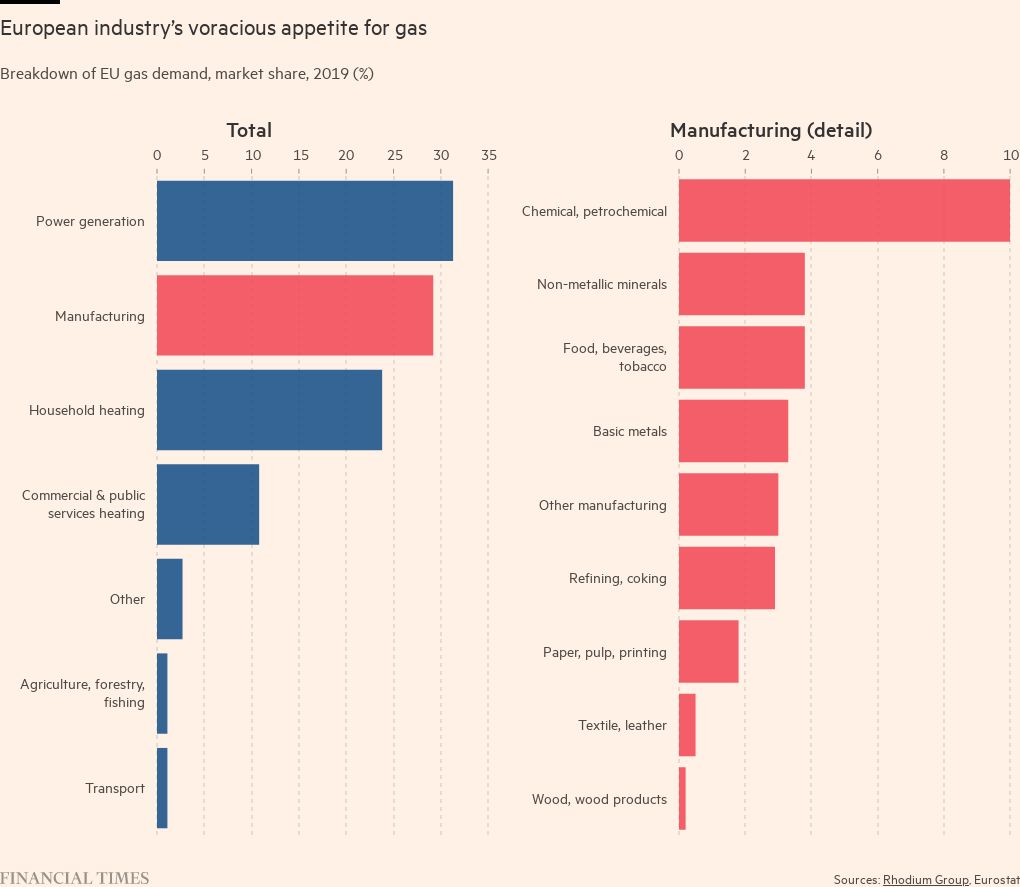

The power plant is owned by Evonik, one of Germany’s largest speciality chemical companies, which also runs the park. And its extended lifespan reflects the fears of power shortages in the country, as gas imports from Russia have been cut following its invasion of Ukraine. Governments and manufacturers across the continent have been introducing contingency measures to ensure power supplies continue during the colder months.

Many companies have turned to coal and other fossil fuels to keep their operations going. In Germany — which aims to phase out coal by 2030 because it is much more carbon-intensive than gas — the government has temporarily revived or extended the life of several coal-fired power plants. In addition, all three of the country’s remaining nuclear power plants, which had been due to shut down by December 31, will continue operating until mid-April 2023.

For energy-intensive industries, this power crisis is “very acute”, says Harald Schwager, deputy chair of Evonik. He likens the situation to a patient “at the doctor”, but while the “diagnosis is known, so is the therapy”. In this case, the therapy is improving supplies.

“We have a supply shock,” he says. “One [therefore] needs to find ways and means with investments into energy infrastructure so that the supply can be improved, and prices will then automatically come down.”

Engineers at Evonik, which makes products used in everything from toothpaste to tyres, started contingency planning in March. The company screened all of its production sites to determine how it could replace gas with other energy sources. Some of its smaller sites have since started using oil instead of gas but one of the biggest changes has been to keep the coal-fired power plant in Marl running until 2024.

One challenge, says Schwager, has been to ensure sufficient supplies of coal to operate the plant. Evonik has already stockpiled enough coal to keep the plant functioning over the coming winter months of 2022-23. While the price of coal has “gone up, the important thing is to make sure we can keep producing”, he adds.

The coal plant had been due to be replaced by a new gas-fired power station. Fortuitously, given the current concerns over natural gas supplies, that plant had also been equipped to burn other sources of fuel, including liquefied petroleum gas or LPG — a byproduct from refining crude oil. Using a pipeline connected to a nearby refinery owned by BP, Evonik has been able to pipe in LPG to help power the plant and reduce the amount of gas needed.

The net result of these measures is that Evonik has been able to reduce its natural gas needs by 40 per cent. Costs, however, have inevitably risen — the company’s energy bill has jumped roughly €500mn, says Schwager.

For chemicals groups, energy is just one of a number of costs that have risen this year amid wider inflation. However, Schwager is keen to stress that Evonik has maintained its financial outlook for the remainder of the 2022 financial year. Earlier this month, the company reported broadly in-line core profit for the third quarter as higher selling prices offset increased variable costs.

“Evonik has done a good job of cutting natural gas consumption,” says Sebastian Bray, chemicals analyst at Berenberg in London. “The company’s earnings have generally proven resilient. However, higher working capital requirements resulting from elevated energy and raw materials prices may make cash coverage of dividends in 2022 difficult.”

Evonik’s shares are listed on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange, but it also has a large cornerstone investor. Germany’s RAG Foundation, which was set up to help finance the social costs and long-term liabilities associated with the ending of subsidised coal mining in 2018, holds a 56 per cent stake.

Not every large manufacturer has been able to adapt to the energy crunch in such a way, though. BASF, the world’s largest chemicals group by revenue and a significant user of natural gas for its processes, revealed in October that it had spent €2.2bn more on gas at its European sites in the first nine months of 2022 than it did in the same period last year.

Martin Brudermüller, BASF chief executive, said the European gas crisis, coupled with stricter industry regulations in the EU, was forcing the company to cut costs in the region “as quickly as possible and also permanently”. The cuts were necessary to “safeguard our medium- and long-term competitiveness in Germany and Europe,” he added.

Brudermüller is not alone in warning that the energy crisis will have a potentially devastating economic impact on Europe.

“Soaring energy prices are currently precipitating an alarming decline in the competitiveness of Europe’s industrial energy consumers,” the European Round Table for Industry said in a letter to the European Commission last month.

Schwager, however, who was a board member at BASF until 2017, plays down fears of disinvestment, stressing that chemical value chains are so interwoven that it would be difficult to disentangle them. German industry, he adds, has a “task in front of us, we have the toolbox to hike energy efficiency”.

Nevertheless, he concedes that investment into energy-intensive “upstream areas”, such as new power plants, will be more likely happen in other regions where energy is cheaper. Europe, he says, will attract investment into innovation for “downstream” products closer to the customer.

The chemical industry, he suggests, needs “massive investment” for the long term: “[The idea that] we will all run off and go somewhere else, that just won’t happen — we think in decades, and we want our investments to keep running for decades.”

Comments