3D printing and ‘reshoring’ offer limited protection to supply chains

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Sometime in the spring of 2020, Sam O’Leary’s phone began ringing off the hook.

The callers were managers from the auto and aerospace industries. They were all seeking help from his industrial 3D printing business in Germany, SLM, in producing vital parts that were suddenly becoming scarce as the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted international shipping.

“I didn’t do a single day away from the office,” says O’Leary, who took to showing off the company’s specialised machines to clients over video calls. His customers’ worries were always the same, he says: “I’ve got a massive problem, I need to de-risk, I need to reshore.”

SLM’s customers had hitherto used its technology for niche applications, such as producing gooseneck brackets for planes and brake callipers for performance vehicles.

But, despite the increased cost and complexity of 3D printing metal components, they turned to the technology for more commonplace parts — such as hinges that keep regular car seats in place.

So, while many other industrial businesses saw their order intake slow to a standstill, revenues at the Lübeck-based company — whose shares had fallen to record lows before the pandemic hit — grew by more than a quarter in 2020.

Sales were on track to have increased by a similar amount in 2021. For 2022, O’Leary expects SLM’s sales to grow by 40 per cent.

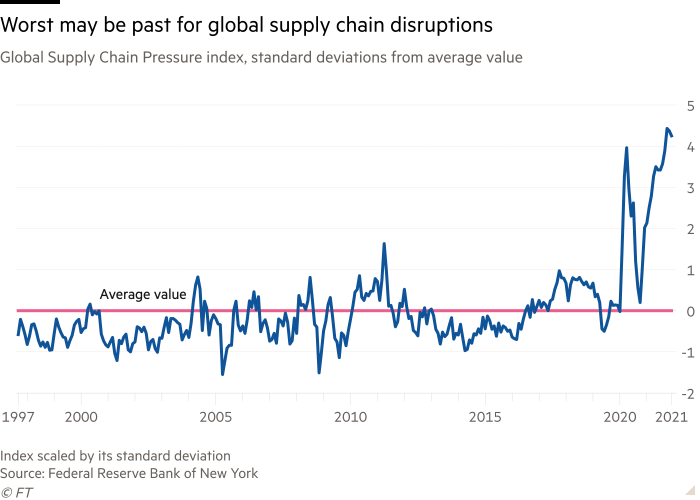

High-profile disruptions to global supply chains in the past couple of years — including the temporary blockage of the Suez Canal, floods and fires in Texas and Japan, as well as ongoing semiconductor production bottlenecks — have led to similarly rosy forecasts for the rest of the so-called “additive manufacturing” sector.

Last year, a study by Lux Research estimated that the market for 3D printed parts, which was worth $12bn in 2020, would grow to well over $50bn by the end of the decade.

Governments across the world have sought to address how, and where, components are made. In Germany, the recent chronic shortage of semiconductors led to millions fewer cars being produced than customers wanted to order. As a result, it is one of many countries to have pledged to support the “reshoring” of crucial component manufacturing to protect their economies.

But, despite such enthusiasm, evidence increasingly points to the fact that businesses like SLM are serving a small market.

A survey of European companies conducted by EY in the early spring lockdowns of 2020 found that more than four-fifths were considering bringing their supply chains closer to home. When the same survey was conducted in April last year, however, that view was shared by just 20 per cent of respondents.

Similarly, only 15 per cent of the multinational companies surveyed by the Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce (DIHK) said they would relocate production.

Their stance was echoed by sports goods group Adidas. Just five years ago, the company launched a scheme to build factories in Germany and the US that would use local materials and advanced manufacturing techniques, such as 3D printing, to produce bespoke trainers for nearby customers.

It had to all but abandon this plan as the Covid-19 pandemic began. But, after supply chain disruptions cut Adidas’ revenue growth by around €600 million in the three months to the end of September 2021, boss Kasper Rorsted was adamant that he had not changed his view on reshoring manufacturing.

“We have approximately 800,000 people deployed in our [suppliers’] factories,” he said in November. “It is an illusion to believe that you can move an industry that has grown over 30 years in Asia, to a very sophisticated industry, to some regions.”

Even if that was theoretically possible, Rorsted added, raw materials would still need to be sourced from around the world to produce the parts, making the prospect of reshoring a “total illusion”.

“You wouldn’t even be able to find the people [that would need to do the work currently being done in Asia],” he said.

Economists in Germany are also unconvinced.

“If the EU were to decouple even partially from international supply networks, this would considerably worsen the standard of living for people inside the EU as well as for its trading partners, and should thus be avoided by all means,” warns Alexander Sandkamp. He is one of the authors of a study by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy that suggested that regionalising production would cost Europe hundreds of billions of euros.

The recent flood disasters in Germany, which cost the country €40bn, according to insurance group Munich Re, was further proof that “shocks can also occur on our doorstep,” Sandkamp adds.

Even SLM’s O’Leary is quick to add a caveat to his company’s bullish forecast.

“We work primarily with regulated industries,” he says. “So, if you’re in an aerospace supply chain . . . you don’t just buy a 3D printer and say: ‘OK, well, I’ve decided to move away from my supplier wherever [they are] in the world and I’m going to do this in-house’.”

A recent development programme with a major UK aero-engine manufacturer, he adds, took two years to get up and running, due to the time needed to install the necessary machines on-site and get the necessary approvals from Britain’s Civil Aviation Authority.

“The demand is definitely increasing,” says O’Leary. “But there’s also a reality in that this is a technology and a change that is regulated and takes time.”

Additional reporting by Olaf Storbeck

Comments