A whiff of ‘Global Britain’

This article is an on-site version of our Brexit Briefing newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every week

The culture secretary Oliver Dowden caused a ripple last week by announcing that John Edwards, the current privacy commissioner of New Zealand will head up the UK’s own Information Commissioner’s Office.

The appointment has a heady whiff of “Global Britain” about it, and in an interview with the Daily Telegraph that will have cheered the Brexit faithful, Dowden said the appointment was part of a drive to achieve a “data dividend” for the UK after quitting the EU.

But the real question for the coming months, as the government prepares to launch a consultation on the UK’s post-Brexit data regime later in September, is “what dividend?” — given a quite narrow set of constraints that Brexit imposes on the government.

The UK absorbed the EU’s cumbersome General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) into UK law during the Brexit process, but will now have to be very careful about the way it seeks to tweak those rules in search of potential commercial competitive advantage.

Because while in theory the government of the UK, as a “sovereign equal” to the EU, has a free hand to set its data regime as it pleases, in practice, it cannot become too laissez-faire. Otherwise, it risks losing the “data adequacy” determination that was granted this year by Brussels.

This decision, which is unilaterally determined by the EU and can be revoked at any time, allows data to flow freely between the UK and the EU and is hugely valuable to British business.

Losing that adequacy arrangement will force companies to fall back on expensive alternatives such as registering “binding corporate rules” with EU member state data commissioners, or reverting to the use of “standard contractual clauses”.

George Riddell, director of trade strategy at the EY consultancy, says losing adequacy would cost a large corporate “millions” of pounds a year, and affect many of those companies — in life sciences and tech — that are foundational to the government’s vision for post-Brexit Britain.

The government clearly knows this, which is why it worked so hard to win a data adequacy agreement in the first place during the trade agreement negotiations last year. (This was in conspicuous contrast to many other fields such as chemicals, cars or pharmaceuticals that were forced to accept significant new barriers to trade with the EU in pursuit of reclaiming sovereignty.)

So what next?

The reaction to the Dowden interview last week in both Brussels and London spoke to the tricky risk-reward calculation that now faces the government.

In Brussels, an EU spokesperson said the European Commission was monitoring the UK’s decision “very closely”, while back in London, William Bain, head of trade policy at the British Chambers of Commerce, asked for “concrete assurances” that the adequacy relationship with the EU would not be put at risk.

But unavoidably, the adequacy finding is at risk, and not just from the European Commission or Council. The greater threat, arguably, comes from the European parliament and “data activists” that have already demonstrated (for example in the Schrems case that led to the striking down of US-EU data sharing agreements) how the European Court of Justice enforces EU data laws.

The difficulty is that the UK’s drive for more openness, flexibility and a lighter-touch approach is going to find itself in constant tension with the direction of travel in the EU, where data regulation is being driven into tighter and tighter corners in the courts.

Insiders say both Dowden and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, while mindful of these risks, may not be ultimately deterred by them, given the investment that is going into getting post-Brexit data regulation right, with staffing levels ramping up in the department.

The consultation proposals will, when published, “raise some eyebrows”, according to a person who has seen them, setting off what could be a quite intense debate about how to manage that hunt for a data dividend.

In the nature of global trade, the UK cannot be too far out on a limb, and the evidence of the “Brussels effect” in this field is clear. That is why South Korea has just applied for adequacy with the EU and many US corporates find themselves using the same cookie banners that Dowden is promising to do away with, simply to mitigate cost and risk of falling foul of the EU laws.

And ultimately, if the UK is too successful in accruing a commercial advantage from lighter-touch or smarter data regulation, the EU can always tilt the cost-benefit analysis against Britain by ending its adequacy deal. As we’ve seen in a host of other areas, from financial services to mussel farming, the EU is not averse to regulatory arm-twisting.

Still, says EY’s Riddell, there should be limited space for the UK to improve its offer outside the GDPR remit — which regulates the transfer of sensitive personal data — by signing digital partnership agreements with non-EU countries.

Such deals can improve cyber security co-operation and other facilitative measures, such as acceptance of e-signatures and streamlining standards for permission of different kinds of data between countries, all of which will help the UK improve its position on digital trade.

Even inside the narrower GDPR envelope there may be some scope for tweaks that don’t end adequacy, for example, in loosening consent mechanisms needed for the repeat processing of personal data, or how prescriptive the regulator needs to be in order for compliance to be maintained.

Whether all of that amounts to a significant “dividend” a decade from now, only time will tell, but the government is determined to try.

Do you work in an industry that has been affected by the UK’s departure from the EU single market and customs union? If so, how is the change hurting — or even benefiting — you and your business? Please let me know by emailing brexitbrief@ft.com.

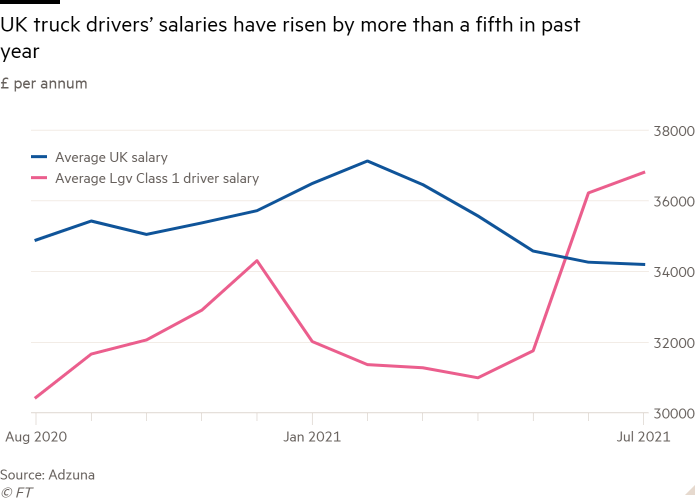

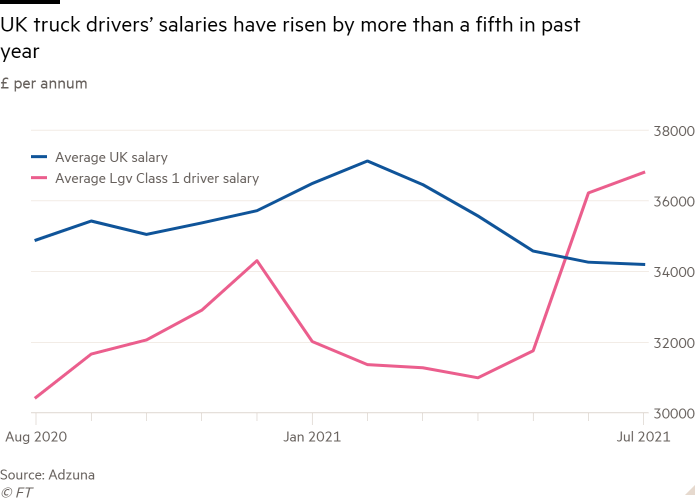

Brexit in numbers

The logistics and truckers shortage rumbles on and is likely to get worse as we head into the pre-Christmas stock up season, according to the industry.

For now, to the frustration of trade groups such as Logistics UK, the government is holding its line on refusing to replicate its seasonal worker scheme for agriculture for truck drivers, in order to enable recruitment from the EU to help shrink the driver deficit in the short term.

Not surprisingly in the binary world of Brexit politics, this issue has been seized on by those wanting to demonstrate the costs of Brexit, but the picture is more complicated than that, according to Kieran Smith, the chief executive of Driver Require, a recruitment agency.

Based on the Office for National Statistics’ quarterly labour force survey figures, at the start of the pandemic about 40,000 of the 300,000 truck drivers in the UK were from the EU, but by the end of March 2021, that figure had halved to about 20,000.

Approximately 5,000 have returned since April this year, but that 15,000 EU driver deficit is dwarfed by the 50,000 UK-based drivers that have left the profession since the pandemic began, with a disproportionate number of those being drivers aged over 45.

So while EU drivers might help in the short term, the bigger problem is a top-heavy profession with relatively poor working conditions which is struggling to attract domestic workers. It’s not yet clear if wage increases will force the necessary adjustment.

Brexit Briefing

Follow the big issues arising from the UK's separation from the EU. Get Brexit Briefing in your in-box every Thursday. Sign up here.

Where Brexit does perhaps play into this is that there are also driver shortages in the EU where wages are also rising, which means that drivers with settled status that might have gone back to work in the UK now have better options at home.

Even if the government did change its position on visas, it might not be as easy as many assume to lure EU drivers to work in the UK on short-term contracts that require more bureaucracy and living further away from home, than if they stayed in the EU.

Our excellent Europe Express newsletter returns on Monday after its summer break. You can sign up for it here.

And, finally, three unmissable Brexit stories

Prominent EU legal experts have backed the British government’s demand to rewrite a controversial section of the Brexit withdrawal agreement that gives Brussels potentially sweeping powers over UK state aid decisions. The intervention supports arguments made by Lord David Frost that article 10 of the Northern Ireland protocol is “redundant” and should be removed. Discover the implications.

The UK’s pig producers have warned they are weeks away from culling healthy animals after labour shortages in abattoirs caused a backlog of 70,000 surplus animals on farms. The National Pig Association is concerned that a lack of workers has hit food production and haulage, with knock-on effects to many UK supply chains. Find out more.

Lastly

, don’t miss Sam Jones’s article about the good health of Austria’s banks, and how the pandemic may mark a turning point as Vienna’s finance capital dream edges closer to reality.

Comments