Cyber specialist out to detect supply chains’ weakest links

Simply sign up to the Cyber Security myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When Kaseya, a Miami-based software supplier, was hit by a cyber attack in July last year, it was not just a problem for the company itself. The hackers also managed to gain access to Kaseya’s customers and, after that, those customers’ own clients. Around 1,000 companies were affected in all. One of them — a Swedish grocery chain — had to close hundreds of stores.

This is not an isolated example. IT security breaches via corporate supply chains are a worry for all technology managers — and one that UK cyber security group Risk Ledger is trying to address. The company, founded in 2018, aims to show businesses exactly how secure their supply chains are. “The supply chain is a very complex environment,” says Haydn Brooks, co-founder and chief executive of Risk Ledger. “We need to solve companies’ problem of understanding the security of their immediate suppliers.”

It is a growing problem, globally. According to cyber security specialist CrowdStrike, attacks via supply chains were up 430 per cent in 2021 as criminals sought fresh ways into companies that had improved their defences.

This escalation comes amid a rising number of cyber incidents, generally, and a move to greater IT integration between companies and their suppliers — which can give a range of organisations access to the same systems.

“Supply chains have ballooned in risk over the past 20 years,” says Brooks. “Twenty years ago, people did not outsource so much. The attack surface has increased.” And the greater interconnectedness, he adds, means an attack can lead to a “chain of dominoes” in which many organisations are affected.

Insurance companies offering cyber cover policies have become increasingly aware of the risks. “The supply chain is critical,” says Paul Bantick, head of global cyber and technology at insurer Beazley. “When we are underwriting, we ask if [the client] is putting supply chains under scrutiny.”

That scrutiny is what Risk Ledger aims to provide. Brooks set the company up after abandoning plans for a career in healthcare. He spent several years at consultants KPMG and Deloitte before deciding to branch out into cyber security with his own start-up. Initial feedback from potential clients was encouraging. “Security friends liked the idea, and said, ‘If you build it, we will buy it,’” he says.

Risk Ledger’s core product is a “map” that gives companies an easy way to look at the cyber security status of all their suppliers. Those suppliers, often under the terms of their contracts with their clients agree to upload details of their security systems to Risk Ledger and to notify it of any changes. If Risk Ledger detects potential problems, action can be taken to fix them. The database is updated continuously, avoiding the need to reassess the supplier’s security every year, or every time the contract is renewed.

As more companies sign up, Brooks is hoping for a network effect. “The very first basic concept was to have a social network,” he explains. “If we can have a social network that allows me, as a user, to understand your security and then allows you to do the same with other users, we can use that social network . . . to map out connections between companies. And we can use that in a way that protects the entirety of the network.”

This could help suppliers as much as the customers that encouraged them to sign up in the first place, Brooks argues. Suppliers can connect with other companies that are already in the system, allowing Risk Ledger to help them cut down on the paperwork, as they will not have to tell all their clients separately about their security status every year. More than 2,500 organisations have shared their supplier profile, the company says, including 12 FTSE 100 companies.

As with any start-up, however, the ongoing challenge for Risk Ledger will be convincing potential clients that it is worth adopting a new system from a small company, especially when businesses are dealing with rising costs.

A further problem is that most companies already have a system in place to verify the security of their suppliers — either using questionnaires or security rating tools, or other companies that specialise in assessing cyber security, such as CyberGRX.

Some companies may also be wary about uploading details of their IT security to a third-party database. Brooks emphasises that protection is in place. No one can access information on the database until they have permission to do so. “It’s not open for the whole world to see,” he says.

Risk Ledger views data protection as a priority. “We take the security of our systems very seriously,” Brooks says. “Selling to security professionals, the first question we get asked is around centralising this data. We try not to centralise any data that could be used in an operational attack so, if a data breach with us were to occur, there’s very little operational data that could be used.” He adds that Risk Ledger receives “surprisingly little pushback” from its clients or their suppliers.

Plenty of companies have signed up to use the system. Risk Ledger now has 68 clients around the world, including, in the UK, the Civil Aviation Authority, BAE Systems Applied Intelligence, Northumbrian Water, City of London Police, Asos and Schroders Personal Wealth.

The public sector has been a strong source of business. “Public sector [organisations] understand the problem,” says Brooks. “It’s quite a tight-knit community, so, as we started showing some initial success in the public sector, a lot of their security teams started chatting to other public sector security departments, which meant we got some really strong organic growth.”

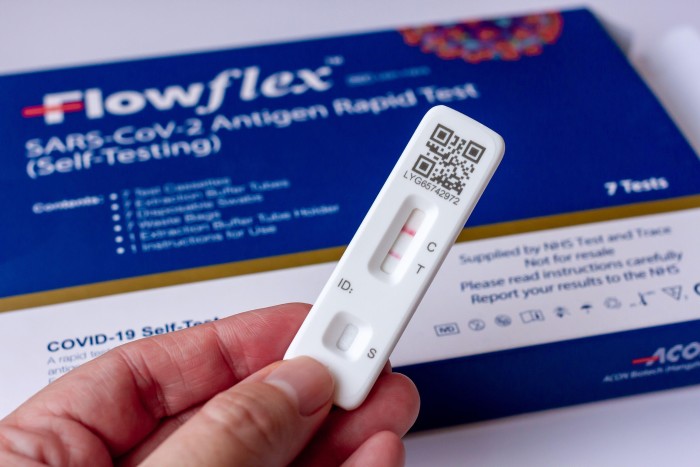

One of the highest-profile clients has been the NHS’s Test and Trace system, which was created to help cope with the Covid-19 pandemic. Mark Logsdon of NHS Test and Trace is quoted in a company presentation as saying: “We had complex supply chains to manage and we were growing rapidly. At the same time, we weren’t just testing and producing results, we also had to develop a delivery network akin to Amazon to support all of that activity.”

Risk Ledger says it gave Test and Trace information about security across several layers of its supply chain, and helped it to discover that one of its chemical suppliers was vulnerable to a malware attack.

The next stage of Risk Ledger’s development will be to move on from mapping potential risks to integrating information about real-life attacks. That will give clients an insight into where attacks are happening and what the impact on them might be. “We are just starting to look at that now,” says Brooks. “We are building a set of tools on top of the core network to allow people to understand what attacks are happening.”

But new products will require more staff and more resources — and Risk Ledger, like most early-stage start-ups, is lossmaking. It does not publicly disclose its revenues, although it says that they tripled between 2020 and 2021, and are growing at a similar rate this year.

So far, the company has raised £3.5mn of funding, mostly from venture capital organisations. Backers include Finland’s Lifeline Ventures and Firstminute Capital, which was set up by lastminute.com co-founder Brent Hoberman. Risk Ledger is now seeking a fresh funding round, in which it hopes to raise more than the total raised to date. Brooks is hoping to get the company to the stage where it can float on the stock market as a standalone business, rather than have it acquired and subsumed into a larger organisation.

Staff numbers have grown with the business. The company was started by Brooks and Daniel Saul, a friend of a flatmate who became Risk Ledger’s chief technology officer. Today, there are 34 full-time staff — a number that is expected to increase to around 40 by the end of the year. All staff are background-checked to UK government standards, because of the number of public sector clients the company serves.

Unlike some start-up chief executives, Brooks values a physical office — Risk Ledger’s is near London’s Liverpool Street station. “Although we went fully remote for the pandemic, me and my co-founder never really wanted to build a fully remote company. We like seeing people, we like working with people.”

In the longer term, Brooks has big ambitions. “What our company is trying to do is build a platform that can protect the entire world’s complex ecosystem of companies from cyber attacks,” he says. First and foremost, though, Risk Ledger’s aim is to show clients it has prevented attacks and the damage they can cause. “It’s why a lot of people work for us. It’s quite a nice goal to get out of bed for.”

Comments