Green patents slow as net zero deadlines edge closer

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Patent activity for low-carbon technologies surged in the first decade of the 21st century, but has slowed significantly since 2013 — causing some concern that the rate of invention will not be enough to meet net zero targets.

A report from the European Patent Office and the International Energy Agency showed that the growth in low-carbon patents filed dropped to just 3.3 per cent a year from 2017-2019 from average growth of 12.5 per cent a decade earlier. It has dropped further in the past two years, although this is partly attributed to a Covid-related slowdown in new patents, generally.

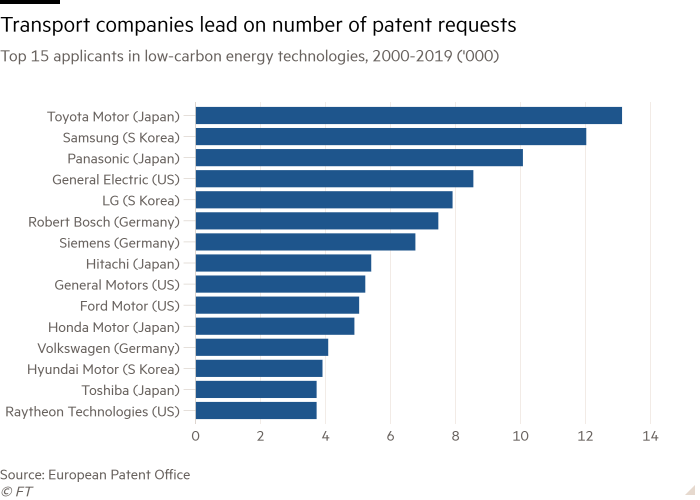

There are some areas where invention has not slowed. Transportation technologies make up 40 per cent of all end-use low-carbon technology patents, and new patents for electric vehicles — including battery or charging technologies — have seen the fastest growth. The busiest applicant in 2000-2019 was Toyota, while five other car manufacturers appear among the top 15.

However, given the slow pace of growth overall, the EPO and IAE report concludes that a boost in inventive activity is needed to meet net zero goals.

Headline figures may not capture the full extent of investment in new technologies addressing climate change, though — as there is no clear definition of a green patent. There are international classifications that cover new low-carbon technologies, such as wind turbines and solar power, but the technologies that are likely to contribute to combating climate change are broader.

“‘Green’ is a funny, subjective word,” says Christopher Hamer, partner at intellectual property firm Mathys & Squire. “There is some good [intellectual property] that is going by the wayside because it’s not seen as pushing the frontiers,” he says. “For example, a soot suppressant for diesel engines is not seen as a sexy technology to take to market in Europe. But you’re not going to make diesel obsolete in 20 years, so why not invest in some of the short-term fixes?”

A report published by Capgemini in 2020 concluded that artificial intelligence has the potential to help organisations meet between 11 and 45 per cent of industry emissions targets set out by the Paris Agreement by 2030. But you cannot directly patent an algorithm. The codes — like Google’s search engine algorithms — are usually treated as trade secrets. An AI use-case or application can be patented, but many of these may not be classified as “green”.

“Tech being developed to mitigate climate risk — for example, for weather forecasting or flood planning or route planning to reduce fuel costs — are only possible because AI is available to support them,” explains Mark Marfé, partner at law firm Pinsent Masons. Across all sectors and technologies, he adds, “AI is an accelerator and can draw out the benefits to a system or technology and make it better or quicker”.

More from this report

Europe’s Leading Patent Law Firms 2022

Patent lawyers condemn Russian expropriation of patents as ‘act of war’

IP waiver is a ‘matter of life or death’ for one Ukrainian lawyer

Testimonial discrepancies: a new strategy for litigators?

China’s courts flex intellectual property muscle across borders

Nations urged to waive IP on vaccines as drugmakers insist current rules are fair

Inability to patent AI creations could hit business investment

Patent offices around the world have also looked at the approval process and how it might help the development of green technologies. The UK Intellectual Property Office, for example, introduced a fast track for green patents, called the “Green Channel” more than a decade ago. Yet, since 2009, fewer than 3,000 patents have been granted through this process.

“From an economic perspective, there is not a lot of reason in fast-tracking patents for green tech,” says Antoine Dechezleprêtre, senior economist at the OECD. It may be useful for start-ups looking to use a patent to access additional funding. But, for larger companies, a slower patent approval process allows more time for research and development before their patent is finalised and made public.

The process again raises the question of how to define “green”. “To use the UK’s Green Channel for patent filings, one has to make a statement as an applicant with a reasonable assertion that the application has an environmental benefit,” notes Chris de Mauny, partner at law firm Bird & Bird. “But it still begs the question: what is an environmental benefit?”

The European Patent Office has its own programme, PACE, which offers to fast-track applications in all technology sectors at no extra charge. The EPO says current data indicate that inventors of green patents use the PACE procedure as often as inventors of other types of patents.

However, the speed of innovation in green technologies will need to increase — and the answer to this arguably sits outside the IP and patent system.

“IP rights, and making it easier for firms to file patents specifically on green tech, will probably have a very small influence,” says Dechezleprêtre. “Climate policies, energy prices, [and] public R&D expenditure will have more of an impact.”

Yasmin Lambert is managing director at RSGI

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments