Syria’s ‘Aleppo boil’ spreads with refugees through the region

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

At first, Wesal Daher thought the bumps on her face were just blemishes. She would apply cream to her forehead and cheeks every day, but the bumps continued to grow, becoming large lesions. Daher didn’t know what to do. “At first they were small like this,” she says, pointing to some bumps that her 10-month-old son, Khaled, has on his leg.

When she arrived in Lebanon last year, after escaping from their village near Raqqa in neighbouring Syria, a fellow refugee told her she had something called Aleppo boil and that she needed to go to a clinic.

First reported in the northern Syrian city in 1745, Aleppo boil, also known as Aleppo ulcer or cutaneous leishmaniasis, is a parasitic disease that causes disfiguring skin lesions, often on the face and hands. It is not spread by skin-to-skin contact, but rather by sandflies, one-third the size of a mosquito, that bite a lesion on an infected person and become a host for the leishmania parasite. When the infected fly bites another person, the parasite is transmitted.

The disease is not unique to Syria, but since the start of the country’s civil war in 2011 it has re-emerged there as a significant threat to public health.

“Syria, in particular the region of Aleppo, has always been endemic of cutaneous leishmaniasis — and we are talking about centuries ago,” says Dr Alvaro Acosta-Serrano, a senior lecturer at Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in the UK. “Before 2011, Syria already had thousands of cases a year. But it was controllable.” Acosta-Serrano and his team are now researching how the war has helped the disease to spread.

The conflict has created the perfect conditions for an outbreak. As the violence intensified, Acosta-Serrano says, efforts to control the disease were abandoned. The health system became increasingly strained as medical facilities were bombed and people fled. Those doctors and nurses who remained were overwhelmed by treating casualties of war.

In many areas, infrastructure was also badly damaged. Puddles of water and piles of rubbish built up, providing ideal conditions for sandflies to lay their eggs. It is not the first time conflict has helped spread the disease; wars in Iraq in the 1990s and 2000s had helped foster similar outbreaks that spread among foreign troops.

Acosta-Serrano’s team estimates conservatively that last year there were 70,000 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in northern Syria alone. He says that number would have been much higher were it not for the work of organisations such as the Mentor Initiative, which provides disease control, and the Syria Relief Network, a group of humanitarian organisations working inside Syria and neighbouring countries. They have set up clinics to treat people in affected areas.

Millions of Syrians have fled their homes since the start of the conflict, some taking shelter in refugee camps in the country and millions of others seeking asylum in Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon. But the camps offered no escape from the sandflies and the disease began to spread. “You have to think of a refugee camp with almost two million people,” says Acosta-Serrano. “They are the size of a city [but with no] infrastructure.” (He puts the number of cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis among refugees in Turkey in the tens of thousands.)

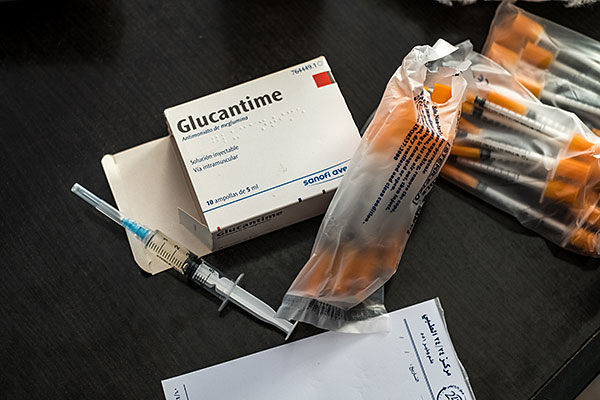

Daher now comes to the clinic in Tripoli, northern Lebanon, twice a week, where a nurse fills a syringe with Glucantime (meglumine antimoniate), a drug introduced in the 1940s to treat leishmaniasis, and injects it under the lesions on her forehead. Both her sons are infected, too. She says when she left her village in Syria last year, she knew just one other woman who had similar symptoms. “But I talk to my family now and they say many people have it there,” she says.

Dr Dima El Safadi, an assistant professor in the faculty of public health at Lebanese University in Beirut, works with Acosta-Serrano collecting information from the clinic in Tripoli where Daher is treated. The number of cases in Lebanon peaked in 2014, Safadi says, because of the number of Syrians coming into the country. More than 1,300 cases were reported that year, according to the World Health Organization.

Lebanon’s ministry of public health began providing treatment in late 2014 at the subsidised rate $2 per person, in conjunction with the use of insecticides to eradicate the sandflies. Almost all cases reported in Lebanon have been in Syrians and the number has fallen to a few dozen new cases so far this year. However, this reduction is not solely a result of the government campaign, Safadi says, but also the increasingly tight border controls between Syria and Lebanon.

She sifts through the files of her Syrian patients, listing where the new cases have come from — Hama, Idlib, Raqqa, Tartus and Aleppo. But, she says, so far there has been little evidence of transmission inside Lebanon. “The sandfly is present here, and the host patient is present here [but] I don’t understand why the life cycle is not present,” she says.

Safadi’s patients, however, are helping to provide a clearer picture of what is happening inside Syria. “I think now there is an outbreak in Idlib,” says Safadi. “There are 10 or 15 patients from Idlib and, when asked how many people from their family are infected, they tell you all [of them] — or at least two or three. It’s dangerous.”

Neshma El Murr came from Idlib seven months ago. He says all of his 10 children were infected. They received treatment for months but he and two of his daughters have not recovered. One daughter, aged 14, has kidney problems caused by Glucantime. “It’s toxic and painful,” says Safadi of the Glucantime treatment. “But it’s the only one.”

Research into treatments and vaccines for cutaneous leishmaniasis has been limited. One reason is that the disfiguring disease is not fatal, making it less of a priority for infectious diseases researchers. “Obviously it’s a disease of poverty, so it’s not that great for a pharmaceutical [company] to produce it,” says Acosta-Serrano. “It’s not a disease that normally affects the first world.” What is really needed, he says, is a safe, affordable, available vaccine. “You can’t control the insect population everywhere,” he says. “But you [could] vaccinate people in endemic areas, and that may have an impact.” In the meantime, controlling the sandfly population and providing treatment to infected people should reduce the current epidemics.

An experimental vaccine is being developed in the US, by Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine, both located in Houston, in co-ordination with the US National Institutes of Health. Researchers say progress has been hampered by a lack of funding.

Meanwhile, some people try to self-vaccinate, using a procedure as known as leishmanisation, which has been practised for centuries. It involves taking a piece of scab from a sore of an infected person and infecting a healthy person in a discreet part of the body, such as a leg. But this process is dangerous — it can lead to leishmaniasis or a bacterial infection — and is not always effective.

For those already infected, it can take months, or even years, for the lesions to heal fully. “All the people in the village were talking about my children — that they have this disease,” says Murr. Both Safadi and Acosta-Serrano emphasise the social stigma associated with the disease. Those infected become isolated, says Safadi, adding that people often avoid socialising or doing business with sufferers, in the belief that they could catch the disease, in turn damaging patients’ livelihoods.

It can be particularly hard for young women who hope to marry. If the lesions take a long time to heal, their faces may be permanently disfigured. “My oldest daughter still has a big mark on her forehead,” says Murr. “Of course, [people] look at her strangely.”

He is concerned about his children who remain in Idlib, while he works in Lebanon to raise money. But the disease is not his main concern. “I’m more worried about the warplanes and the bombing,” he says.

Comments