TikTok Shop’s troubled UK expansion: staff exodus and culture clash

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A culture clash between TikTok’s Chinese owners and some of its London employees has triggered a staff exodus and complaints about an aggressive corporate ethos that runs counter to typical working practices in the UK.

The friction has centred on the social media company’s ecommerce initiative, TikTok Shop, which launched in the UK in October.

Joshua Ma, a senior executive at China’s ByteDance — owner of the viral video app — and the head of ecommerce at TikTok Europe, outraged London-based staff at a dinner this year when he said that, as a “capitalist”, he “didn’t believe” companies should offer maternity leave.

The episode is emblematic of a broader clash within the ecommerce division. At least 20 members of the London ecommerce team — around half of all its original staff — have left since TikTok Shop’s launch, while others say they are on the brink of quitting. Two employees have been paid settlements over working conditions.

“There are people leaving every week, it is like a game — every Monday we ask who has been fired, who has quit,” one current employee said.

The visit by Ma was to check in on the launch of TikTok Shop in its first market outside Asia. The feature is an effort to bring QVC-style shopping to British users. Brands and influencers broadcast live on the social media app, selling products through a clickable orange basket on the screen.

On Wednesday, TikTok sent an email to staff saying Ma had “stepped back” from his role while it conducted a formal investigation into the comment and other claims brought to the company by the Financial Times. The FT spoke to 10 former and current members of the London ecommerce department, talking on condition of anonymity. The company said it had a clear maternity leave policy in the UK, including 30 weeks of paid leave.

ByteDance raised $5bn in December 2020 at a $180bn valuation, and revenues increased 111 per cent last year to $34bn, according to people familiar with the matter.

It is seeking to justify that valuation by expanding its ecommerce offering, using a model which has proved lucrative for Douyin, TikTok’s sister app in China. Rivals YouTube and Instagram are developing similar features in Europe, while TikTok’s rapid growth and popularity with younger users was recently cited by Facebook parent Meta as a threat to its business.

Ecommerce team members in London said they were expected to frequently work more than 12 hours a day, starting early to accommodate calls with China and ending late as livestreams were more successful in the evening, with “feedback reports” to be filed immediately after.

Images of employees working into the early hours of the morning were celebrated in internal communications as examples of “commitment”, while a handover in which an employee said they would work during their holiday was shared as an example of good practice.

TikTok said employees sometimes have to work flexible hours that “match customer use patterns” and that it aims to make this the “exception, rather than the norm”.

Several employees went off sick with stress while some staff were removed from client accounts or demoted after taking leave.

“The culture is really toxic. Relationships there are built on fear, not co-operation,” a former London-based team leader said. “They don’t care about burnout because it is such a big company, they can just replace you. They coast on the TikTok brand.”

As a source of revenue, TikTok Shop appears to lack traction in the UK, operating at a loss, while many livestreams generate zero sales.

Employees complained they were set “unrealistic targets” of up to £400,000 a month in total sales from livestreams, when a successful stream from an average seller might generate less than £5,000. TikTok takes a 5 per cent commission, which is often waived to entice new brands on to the platform.

Those who failed to meet targets or respond to work requests out of hours were singled out and reprimanded on the company’s internal messaging system, former employees said. One former member of the leadership team said the culture nearly pushed her into a breakdown.

“TikTok Shop has only been operating in the UK for a few months, and we’re investing rapidly in expanding the resources, structures and process to support a positive employee experience,” said TikTok. The company offers health and wellbeing support, as well as training and mentorship, it added.

TikTok Shop’s strategy is to source items directly from cheap manufacturers in both the UK and China and sell low-cost products.

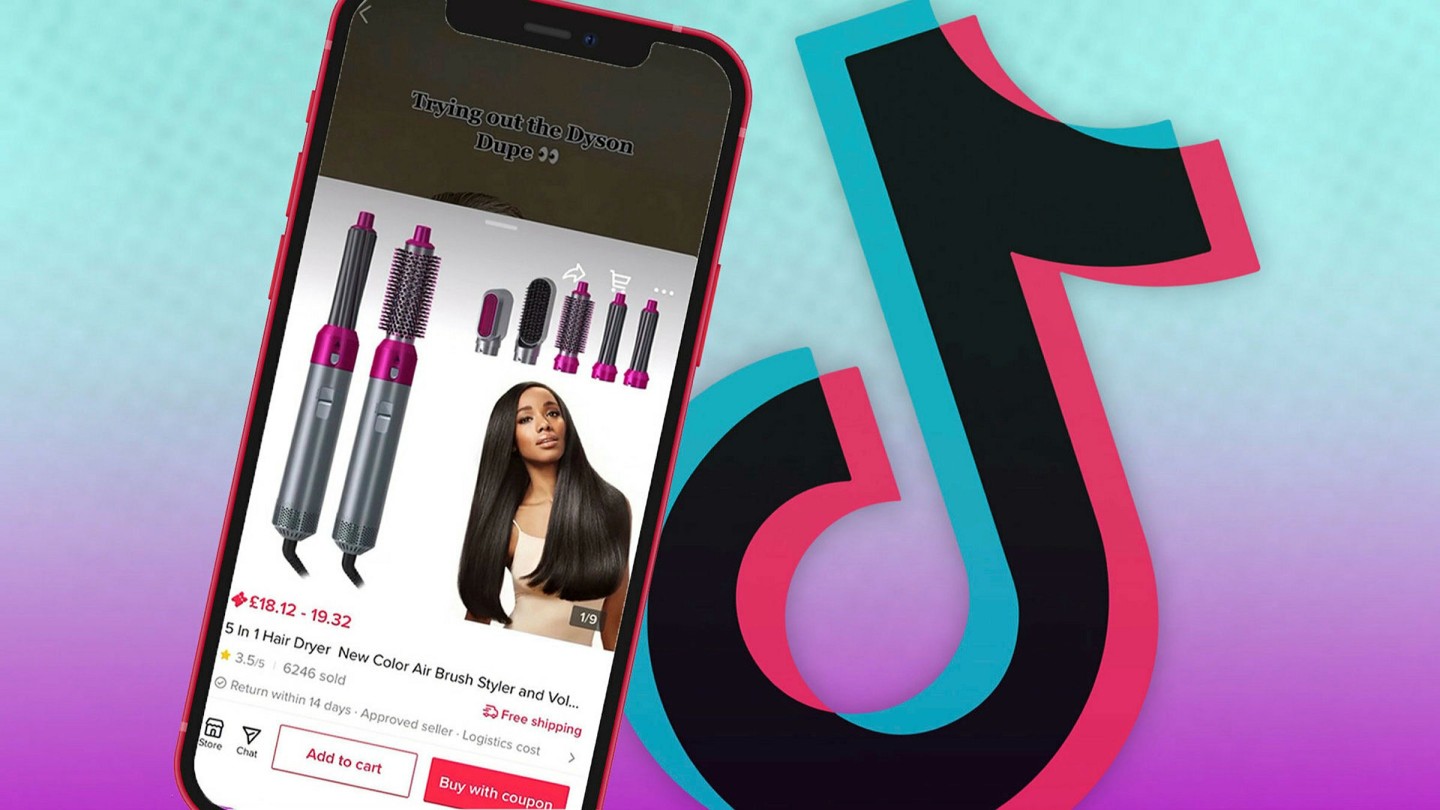

Popular deals include a £14 “Dyson dupe”, a hairstyling device that resembles a Dyson Airwrap, which has a recommended retail price of £450.

Dyson says it does not endorse “inferior copycat products” and has encouraged TikTok to take a more active role in removing “dupe products from sale”. TikTok says it has a team monitoring for counterfeit goods and has strict product guidelines.

Established brands including Lookfantastic, L’Oréal and Charlotte Tilbury have sold products through TikTok Shop. Brands are encouraged to offer flash sales and heavy discounts, which TikTok often subsidises. The running costs of conducting the influencer livestreams, such as studio space and technical staff, are also often funded by TikTok.

“The model doesn’t work because it is a different market and ecosystem in the UK but management doesn’t listen and refuses to make changes,” a current employee said. European brands were uncomfortable with the level of discounting on their products, said employees who dealt directly with brands.

TikTok hired people with experience at ecommerce and luxury brands including Harrods, Asos and Amazon, offering sign-on bonuses and share options.

Staff used their contacts to attract big brands to the platform but some said their long-term professional relationships with these companies were ruined by having to aggressively negotiate discounts and then sometimes end contracts without explanation. “I lost credibility with merchants,” said one current employee.

TikTok said it was “constantly learning, iterating and improving [its] service” and is guided by its community, influencers and merchants.

Influencers are expected to stream bi-weekly, receiving a pre-agreed commission for sales. They are sometimes paid a flat fee, but this has been cut recently for some, leading to many dropping out of the partnership.

“The TikTok Shop model doesn’t work in the UK,” said a former employee. “It will only work if the company is willing to listen about how to do it in a culturally acceptable way that works for British brands and consumers.”

Additional reporting by Hannah Murphy in San Francisco

Comments