Pressure builds for the return of cultural jewellery

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

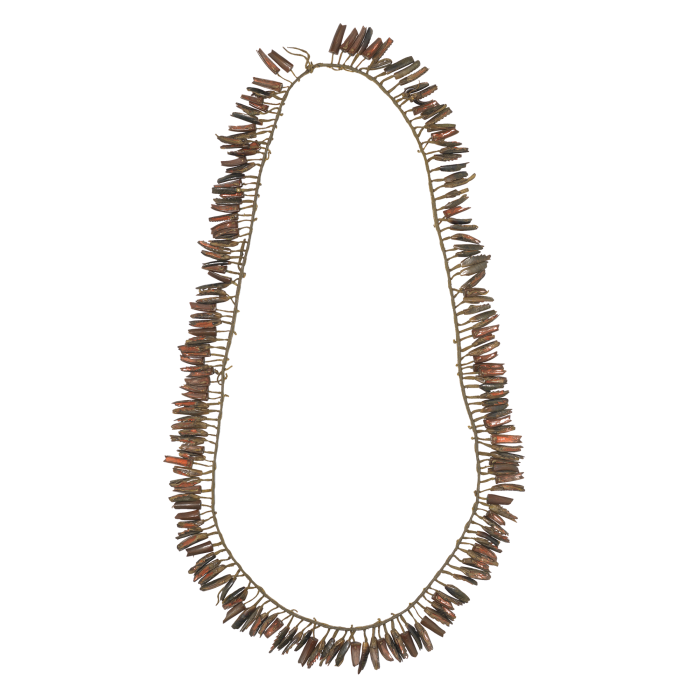

There is a beauty and a delicacy to the deer hoof necklace that was taken from a Lakota Indian slain during the Wounded Knee massacre at the Pine Ridge reservation, South Dakota, in 1890. The shards of hoof hang like precious gem chips from its leather thong.

It is one of 49 objects from Glasgow museums that the city’s council voted to repatriate in April — in one of the UK’s largest reparation agreements and the largest for Scotland. Twenty-five items will be returned to the fallen Lakota’s ancestors in the US, while Nigeria will receive 17 Benin bronzes, taken from the Royal Court of Benin during the British Punitive Expedition of 1897, and seven antiquities, most of which were stolen from Hindu temples, also in the 19th century, will be returned to India.

“If removed under illegal or immoral circumstances, then we have a responsibility to return objects,” says Duncan Dornan, head of museums and collections at Glasgow Life, the charity that runs the city’s museums. “We don’t perceive this as opening the floodgates, a term that has been used. The majority of objects have not been acquired under questionable circumstances.”

This move by Glasgow is being replicated by other institutions in the UK as well as across Europe and the US, as pressure builds — both from within museums and academic circles — for a reassessment of the colonial legacy and for the return of cultural artefacts from communities in Africa and elsewhere.

In August, London’s Horniman museum agreed to return 72 Benin objects. The announcement came following a request in January from Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM) for the items’ return.

The significance to Nigeria of the Benin artefacts was explained by the late Prince Edun Akenzua, Enogie [Duke] of Obazuwa, a member of the royal family of Benin and a leading campaigner for the return of the bronzes. They are “like our own diaries. Whatever was significant the Oba [King] would tell the guild of bronzecasters to cast it in bronze. To keep a record. So taking them away was like yanking off pages of our history.”

According to a report commissioned by the French government in 2018, 90 to 95 per cent of Africa’s cultural heritage is held outside the continent.

The Benin bronzes — along with the Elgin Marbles taken from the Parthenon in Athens in the early 19th century — have become a focal point for the debate on the repatriation of historical artefacts from the world’s museums. Made of brass and bronze, they include elaborately decorated cast plaques, commemorative heads, animal and human figures, items of royal regalia, and personal ornaments.

One of the largest collection of Benin bronzes is held by the British Museum, which has more than 900 items. One of its most striking pieces is an ivory armlet inlaid with brass, which features depictions of Portuguese emissaries or traders and is thought to have been made in the 18th century.

The museum has had several requests over the years to return its Benin bronzes, but says its hands are tied due to parliamentary acts that prevent it, alongside the UK’s other national museums, from disposing of objects in its collection.

However, the museum argues it has positive relationships with the royal palace in Benin City and with NCMM and has discussed ways of sharing and displaying objects from Benin.

It is also a member of the Benin Dialogue Group, which brings together museums from Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK with key representatives from Nigeria, including the Benin Royal Palace and NCMM.

In October, a former UK culture minister, Ed Vaizey, introduced a debate in the House of Lords calling for a reform of one of the parliamentary acts to give museums more power to address requests for repatriation.

The director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Tristram Hunt, has also been outspoken on the matter. In July, he said: “It should be the responsibility of trustees to make the case for what should and should not be in their collections and, at the moment, they don’t have that right because the 1983 [National Heritage] Act means they are legally unable to do so.”

In the V&A’s latest annual review he also referred to talks with Ghana around the V&A collection of Asante court regalia, including gold ornaments, rings and badges, which entered the collection following the looting of Kumasi, the state capital, in 1874. “We are optimistic that a new partnership model can forge a potential pathway for these important artefacts to be on display in Ghana in the coming years,” he wrote.

But restitution is not always about the return of objects. In 2018, following discussions with the Ethiopian embassy, the V&A’s Maqdala 1868 collection was moved to a more prominent display and the labelling was updated to explain how these objects came to the museum — they were taken by British troops at the siege of Magdala in 1868.

The star of this collection is a crown made from gold and gilded copper, with glass beads, pigment and fabric, made in Ethiopia around 1740. The V&A believes it was probably given to an Ethiopian church at the death of an emperor, by his family, to ensure continuing prayers for his soul.

The Pitt Rivers Museum, part of the University of Oxford, is involved in a different kind of reconciliation project involving the east African Maasai tribe. The museum has already agreed the return of Benin bronzes, as have the universities of Cambridge and Aberdeen.

Laura Van Broekhoven, director of the Pitt Rivers Museum and professor of museum studies, ethics and material culture at the University of Oxford, says that, as part of a project in 2018 which also involved the Horniman museum and Cambridge university, a visiting group of Maasai were shown a bracelet from the Pitt Rivers collection and six others held at Cambridge.

“When the bracelets were put on the table, to them it was like the dead bodies of their fathers being put on the table,” she says. “The only information we had about them was a label with a big question mark. The bracelets were, in fact, orkatar, which were handed from a father on his deathbed to the eldest son. It would never be given away.”

That is also the case for a Maasai necklace in its collection, which represents a marriage contract. It is given to a woman on her marriage, committing her husband’s family to looking after her and her children. “For a family to lose such an item would bring bad luck,” says Van Broekhoven. “Your cattle would die; your children would be stillborn.”

She adds: “For the Maasai it’s not so much about the objects needing to return, more the need for a reconciliation ceremony. There is a process for this whereby the clan who did the murder pays 49 cows to the clan of the murder victim. We are hoping this ceremony will take place in Kenya and Tanzania next summer.”

Comments