Asos and Boohoo rip up centuries of British retail heritage

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In 2005, the year Sir Philip Green’s Arcadia group paid his wife £1.2bn as part of the biggest dividend in UK corporate history, Asos reported annual sales of £13m.

It was only just emerging as a fashion retailer, having previously been known as a website for buying items “as seen on screen” — such as Samuel L Jackson’s “Bad Mother Fucker” wallet from Pulp Fiction, the tiger underpants worn by Robbie Williams in the “Rock DJ” video, and the chairs from the diary room in Big Brother.

This week, Asos snapped up Topshop, once the jewel in the Arcadia crown, from its administrators for £265m.

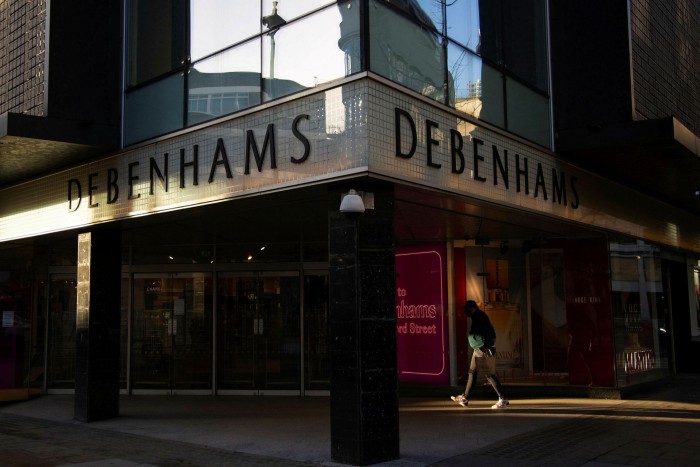

Online fashion rival, Boohoo, whose chief executive John Lyttle was once in charge of buying at Arcadia, is likely to acquire Topshop stablemates Burton, Dorothy Perkins and Wallis. Boohoo has also bought the remains of collapsed department store chain, Debenhams, for £55m.

The flurry of recent purchases means that more than three centuries of British retail heritage have been salvaged by companies with a combined age of 36 years.

“There have always been culls of fashion brands from time to time, but Covid has accelerated it,” said Peter Williams, a former Selfridges chief executive who has served on the boards of Asos and Boohoo. “It’s been just enough to kill off some of the more fragile ones.”

Asos and Boohoo — which are listed on London’s junior exchange, Aim — both now have valuations pushing close to £5bn, making each almost twice the size of venerable Marks and Spencer.

It is a rapid rise from the early days, when Boohoo’s founder, Mahmud Kamani, used to sleep in the back of his van, and Nick Robertson, who set up Asos, had to sell his car to help pay staff. Mr Robertson only averted another cash flow crisis because of booming sales of a novelty telephone whose ringtone was the Culture Club hit Karma Chameleon.

“Every staff member is told that story,” said Nick Beighton, who took over from Robertson in 2015. “It’s a reminder of where we’ve come from and the dangers of hubris.”

The upstarts found they could lure creative staff from ossified chain retailers by promising fun and autonomy. “People loved the freedom we gave them,” said Beighton, who took a pay cut to move to Asos from nightclub operator Luminar in 2009.

During the early 2000s brands from Arcadia to Marks and Spencer began sourcing from the Far East to cut costs and increase margins. But, according to Eva Pascoe, who ran Arcadia’s first ecommerce operation in the late 1990s, it also increased lead times.

“Store campaigns were planned six months in advance but online you could see everything in real time,” she said. “You have to feed it at a faster pace”.

Asos and Boohoo did not have sufficient scale to manufacture in Asia, so they sourced from closer to home. That meant they could launch new designs much quicker — a key competitive advantage as social media started to influence shopping habits — although it led to later controversy over working conditions in factories in places such as Leicester.

Beighton and Lyttle are both white men in their early fifties, but they employ young staff from diverse backgrounds, and listen to them.

“You walk into the Boohoo offices and you’re looking at their customers,” noted Williams. The average age of employees at both companies is below 30.

Beighton recalled how a junior buyer who told him why the company’s clothes “were not hot enough” soon found herself explaining the issues to a room full of senior leaders. The ranges quickly improved.

By contrast, Pascoe described the Arcadia management team around Green as “more like a fan club” with key decisions increasingly taken by the Monaco-based billionaire.

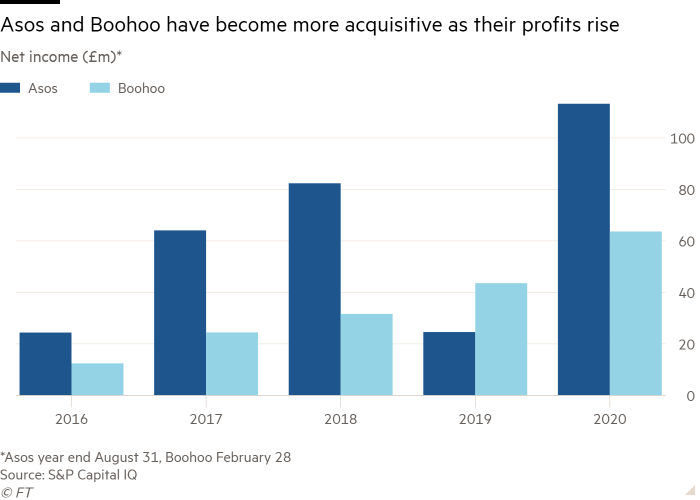

Boohoo and Asos poured money into technology and digital marketing. Neither company has ever paid a dividend.

As their sales, profits and share prices have grown, they have become more acquisitive. Although Boohoo has more deals under its belt — acquiring Karen Millen, Coast, Oasis, Miss Pap and Warehouse over the past 18 months alone — Asos has also sized up plenty of targets.

“We’ve looked at hundreds of things. I can’t tell you how many NDAs I’ve signed,” said Beighton. At one point, the company came close to acquiring Net-a-Porter, now owned by Swiss group Richemont.

But he immediately saw the potential of Topshop because Asos already sold its products alongside its own designs. Topshop sales on asos.com grew 41 per cent last year — compared with just 5 per cent on Topshop’s own website. Asos will also take on the Topman and Miss Selfridge brands and its own designs will start appearing towards the end of the summer.

“During the due diligence I spoke to people at Nordstrom, Zalando and other wholesale partners about Topshop,” said Beighton. “I felt more passion from them for what this brand could do than I got from its own leadership team”.

“The brand was not distressed, the business was. We have liberated it from that business”.

Asos and Boohoo expect that rapid growth in online sales will eventually compensate for the absence of stores. Before the pandemic, online sales at both Topshop and Debenhams were around a fifth of the total and there is plenty of evidence that both companies were ineffective at turning browsers into buyers.

Pascoe said that in the late 1990s, Arcadia had been in the vanguard of ecommerce thanks to Zoom, a joint venture with the publishers of the Daily Mail.

But when Green bought the company he closed it down. “They had all the aces — but they didn’t play the hand. It took them 15 years to catch up,” she said.

“It’s a different sport online,” added Andrew McGarry, a digital marketing consultant. “It’s no good being premiership quality on the high street but championship level online”.

Comments