Smoke clouds obscure India’s solar revolution

Simply sign up to the Renewable energy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

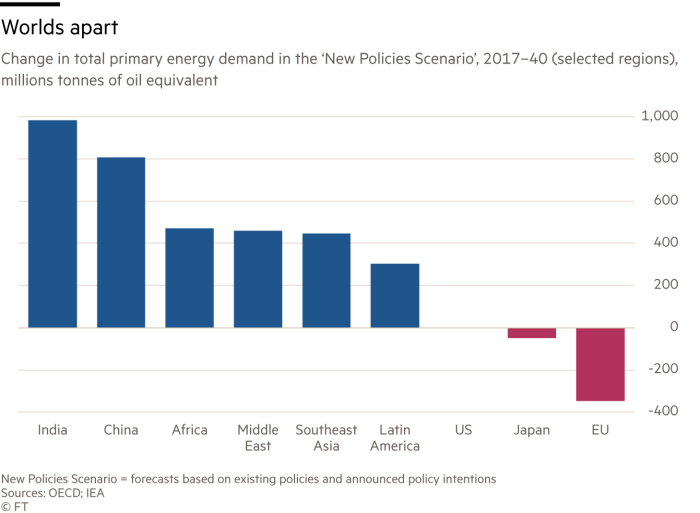

India is targeting an economic expansion of gargantuan scale over the next few decades. The country, with a population exceeding 1.3bn and annual per capita income below $2,000, has become the world’s fastest-growing big economy.

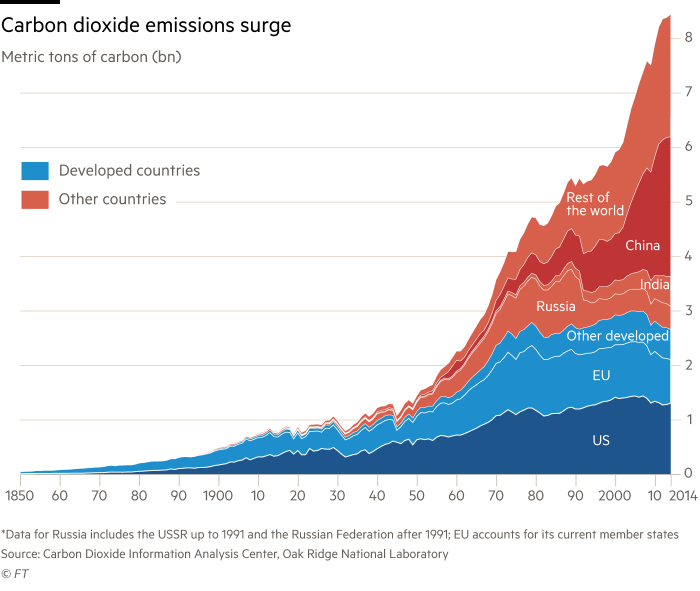

But while India’s annual economic growth — about 7 per cent over the past two years — promises to lift millions out of poverty, environmentalists have warned that unless the country changes its energy mix dramatically, it could have dire consequences for the global climate. Plentiful domestic coal reserves has meant India has long relied overwhelmingly on the highly polluting fossil fuel to power its economy.

Soon after taking office in 2014, the government of Narendra Modi, prime minister, made one of the most remarkable renewable energy pledges of any government to date. It promised that by 2022, India would create 100,000MW of renewable energy capacity — equivalent to 40 per cent of the country’s entire installed power generation at the time of the announcement.

Since then, investment in India’s solar sector has boomed and it is now a key market for the global industry.

Among these investments is world’s largest solar project. Stretching across more than 10,000 acres of desert in India’s northern state of Rajasthan, at a site where temperatures frequently top 40C, the Bhadla project is taking shape.

It is the centrepiece of the government’s ambitious plans for a rapid acceleration of renewable power. Yet analysts are now warning that the overall pace of expansion appears to be slowing.

“For a while, everything was looking so good,” says Tim Buckley, director at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. “But the government policy has gone from very clear to very confused.”

The conditions for Mr Modi’s bold pledge were created in China, where surging production of solar panels led to dramatic price falls — meaning solar power producers in India could compete on cost with coal-fired electricity.

Indian government policy further reduced costs for solar investors — notably by establishing huge solar parks such as the one at Bhadla, where the government promised to take care of supporting infrastructure such as connections to the national grid.

The sheer size of these projects helped to draw in big investors attracted by the economies of scale, says Rishab Shrestha, an analyst at Wood Mackenzie. “Other countries have 100MW or 200MW tenders — so when India has a 1,000MW tender, it attracts a lot of people,” he says.

Among those was Masayoshi Son, the chief executive of Japanese conglomerate SoftBank, who has promised to lead $20bn of investment in Indian solar projects, in partnership with local group Bharti Enterprises and Foxconn of Taiwan.

Optimism around India’s solar push has taken a hit over the past year, however.

The government has imposed a two-year “safeguard duty” on solar panel imports, in an effort to boost local production. But this means potential producers would again face competition from low-cost imports after just two years — making it unlikely to jump-start domestic solar panel manufacturing, warns Ankur Agarwal of India Ratings & Research, a credit-rating agency.

In fact, the past year has brought a sudden decline in bids for projects as investors respond to the higher cost of imported panels.

“It’s really an own goal,” Mr Buckley says, estimating that there will be solar investments worth $7bn-$9bn in India this year, instead of the $20bn predicted before the safeguard duty was introduced.

Alongside the development of giant solar parks, India should consider much smaller solar panels on a more dispersed, local scale, some argue.

BuffaloGrid, a UK-based start-up, is piloting solar-powered communal mobile phone charging stations in India.

“I believe it makes no economic sense for the Indian government to pursue a traditional grid expansion model,” says Daniel Fogg, BuffaloGrid’s chief operating officer. “It makes more sense to look at distributed solar projects,” he adds, insisting that this will be cheaper and more reliable than a system that relies on a big rollout of substations and power lines.

Whatever the mix, most analysts agree that further declines in the cost of solar compared with coal means its share of Indian power generation will continue to grow. However, there is increasing scepticism about solar’s chances of hitting the 2022 target of 100,000MW, given that installed capacity is currently only a quarter of this.

“India’s energy transition is well under way,” says Kanika Chawla, at New Delhi’s Council on Energy, Environment and Water. “But in terms of the government’s priorities, reducing energy poverty comes above cleaning up the energy system.”

The sheer abundance of domestic coal, she adds — as well as continued limitations on storage of solar power — mean that coal-fired generation will remain a big part of India’s electricity mix for the foreseeable future.

Comments