What market optimism misses

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. It’s Katie Martin. Exciting times: Rob is on sabbatical this month. It is one of the best perks of working at the FT, better even than the famous weekly cake trolley (available in the London office only).

While he is away, I am one of the people invited to help out. I’m tempted to use this opportunity to fangirl over the glorious Lionesses or trash some of Rob’s most dearly held beliefs on his own lovingly curated platform, for example by extolling the virtues of Birkenstocks. He hates them, and he’s wrong. This is a hill I will die on.

I will see you again next week. In the meantime, say hi at katie.martin@ft.com, or complain about stuff to ethan.wu@ft.com.

Markets’ mixed stories

No one knows what on earth is going on. Or at the very least, market participants are demonstrating extraordinarily high levels of intelligence by holding two opposed ideas in their mind at the same time. Let’s say it is the latter.

This observation, from Adam Cole, a currencies analyst at RBC, is amazing and sums up the point rather well. The chart tells you that, yes, investors think the Fed will keep on jacking up interest rates from here (see the blue line), but also that very soon after it’s done, it will start hacking them back again (the black one):

This is weird, “entirely unprecedented”, in fact, in Cole’s words. He adds:

Markets have never discounted significant Fed easing within two years while the Fed was still in the middle of a hiking cycle.

So, you are not imagining it. We really are swimming through powerful cross currents at the moment. The dominant theme is flipping from doom/despondency to cautious optimism at quite a clip, which makes sense given this apparent confidence that the Fed will hike till it hurts.

For now, cautious optimism is winning. Global developed market stocks jumped by close to 8 per cent in July, partly due to some resilient earnings from tech megastocks that still have a (dangerously?) outsized influence on broad market direction.

To make this make sense, again, several conflicting things have to be true at the same time. Recessions (proper ones) have to be fine, actually, because of all the easier monetary policy they imply, and/or peak fear is over, and/or markets have already priced in sticky inflation and a hard landing.

Maybe, like UBS Wealth Management, people have been crunching the numbers and figured that wait-and-see is for wimps. From UBS Wealth chief investor Mark Haefele’s note on Friday (my highlights):

Today, after a 26 per cent derating over the past 12 months, the S&P 500 trades at a trailing price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 18.3x, a level that since 1960 has been consistent with annualised returns in a healthy 7-9 per cent range over the next decade . . .

The idea that waiting can be riskier than investing immediately is also borne out in the historical data. Since 1960, a strategy that waited for a 10 per cent correction before buying the S&P 500 and then sold at a new all-time high would have underperformed a buy-and-hold strategy by 80x (yes, eighty). Over the same time period, a strategy of investing immediately after a 20 per cent drop would have delivered an average one-year return of 15.6 per cent. Staying in cash for a year after a 20 per cent drop comes at a significant opportunity cost.

Sure, but there’s a real danger of overthinking all this. As Luca Paolini at Pictet Asset Management points out:

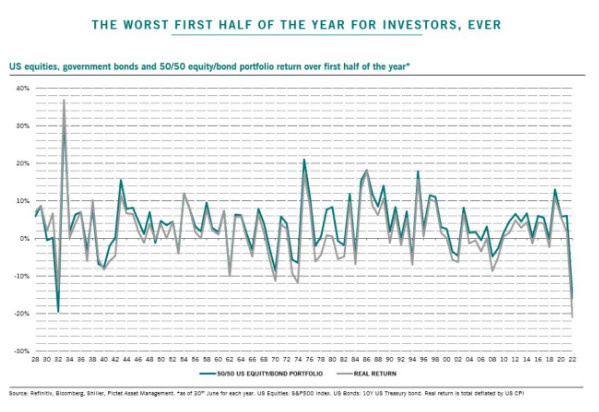

Keep it simple. Equities and bonds are bouncing back mainly because 1H2022 was the worst ever in real return terms. Worse than 1932!

His chart here of how a theoretical 50/50 portfolio of US equities and government bonds would have performed over close to a century rather hammers home that point:

Whatever the cause, this rally could very quickly eat its own tail. Brighter markets mean easier financial conditions — the opposite of what the Fed wants to see, especially after consecutive 75 basis point rate increases. This all just gives the Fed a pass to hit the brakes even harder.

Readers with short-term investment horizons may still be tempted to see how long this has to run, and good luck to you. Investors with longer game plans are generally less inclined to try and be a hero. A few days before the latest Fed’s supposedly dovish pivot, I asked Sonja Laud, chief investment officer at LGIM, whether stock markets had capitulated yet, whether it was time to be brave and jump in.

“To me there’s no rush,” she said. “A number of the big goalposts are shifting. We never really appreciated the value of the globalisation [that we saw] after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolving of the Soviet Union . . . Just-in-time supply chains were a huge benefit to consumers globally and to the profitability of businesses worldwide.”

Now, globalisation is not exactly dead, but it is fraying, reshaping profitability and inflation dynamics. “We’re saying goodbye to the American-led post-World War Two order that we all took for granted,” she said. “It’s history in the making.”

Seen through that lens, it does seem premature to declare this rough patch in markets to be over. The process of figuring out how supply chains and inflation cope in the face of scratchy geopolitics will not be quick, and false dawns will catch investors out. All the clichés are true: stay humble, stay nimble.

Catching Katie’s eye

The growing bet is that the Bank of England will raise rates by 50bp this week, as BoE governor Andrew Bailey has previously hinted. Doing 25bp is so pre-coronavirus pandemic.

Everyone hates Europe. “Investors take a fresh positive look at Europe” is a staple of financial journalism. I know because I’ve written or edited these stories myself on several occasions. Right now, though, Europe is really struggling to maintain a fan club. Goldman Sachs said on Friday it thinks the Euro Stoxx 600 has another 10 per cent to fall this year. “We think the overall market is too complacent about the weakness in growth and risks related to Russian gas supply and Italian politics, which are skewed to the downside,” wrote Sharon Bell and colleagues at the bank.

Unlike every other big equities index, the FTSE 100 is now positive on the year. The first person to tell me this is the Truss Effect will receive the hardest of stares.

If you haven’t already, read this, on the Russian economy. It’s not pretty. Top line, again with my highlight:

a common narrative has emerged that the unity of the world in standing up to Russia has somehow devolved into a “war of economic attrition which is taking its toll on the west”, given the supposed “resilience” and even “prosperity” of the Russian economy. This is simply untrue.

If you can bear it, behold the myriad ways in which the crypto industrial complex relieves people of their money and “Meet the ‘psychic’ cryptovoyants selling bitcoin info to thousands”. (Sifted, with a heroic definition of ‘info’ there.)

One good read

We can’t get enough of Neom, Saudi Arabia’s part-fun, part-insane desert megacity. Its design jumps between “dystopian Death Star evil empire, the apartheid architecture of a post-apocalyptic security-city and a rendering of a glamorised and unlikely central business district seeking gullible investors”, writes the FT’s architecture critic.

Comments