Overdoing it: the cost of China’s long-hours culture

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Gina Wang, a brand manager at Chinese internet company Tencent, starts work most days at 10am and generally finishes at 10pm, but sometimes is still working at midnight. Like many others in China’s tech industry, she reports working long hours of overtime for years. The 29-year-old thinks the burden of work might be contributing to her stomach problems and periods of depression.

She is not alone. Jing Li, 25, an accountant at China’s largest telecoms equipment maker, Huawei, also complains that all she does is work. She feels that she too has succumbed to depression.

“I’ll stay if I can change my position or location next year. If I can’t, I will leave,” Li says, but she faces hard choices if she does. She earned the equivalent of around $40,000 last year, about four times the average annual urban wage in China. At the moment Li feels it is not worth it. She says that although she earns more than many other Chinese workers, “you have to work as if you are four people”.

China’s manufacturing employees have for decades worked long hours in often risky environments, but staff and analysts say the long-hours culture has spread to China’s office workers, thanks in part to the country’s rising internet and technology sector.

Staff at tech companies often cite the phrase “996” to describe their working life — starting work at 9am, leaving at 9pm and working six days a week. Besides generous pay there are perks — some of China’s largest tech companies, such as Baidu and Tencent, routinely provide free transport or meal subsidies for employees who leave after 9pm, according to employees. What the companies do not do, however, is provide the option to work fewer hours.

The problem of long and stressful working hours can be a hidden one. The average Chinese employee spends 44.7 hours a week at work, according to the 2017 China Labour Dynamics Survey, published by Sun Yat Sen University in Guangzhou, covering 21,086 people nationwide. China’s labour law states that workers should not work more than eight hours a day, or 44 hours a week, and that anything more than this should be classed as overtime, which can only be imposed after consultation with worker representatives. At first glance, therefore, the Sun Yat Sen study appears to show that most workers surveyed have a good work-life balance. But the limits are loosely enforced, and more than 40 per cent of respondents to the survey reported working longer than 50 hours a week.

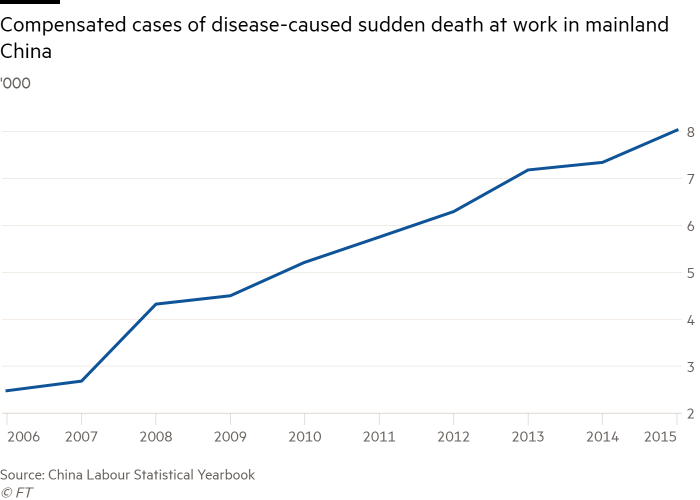

The question of overwork among Chinese white-collar workers, in the tech industry in particular, became a talking point in 2016 when Zhang Rui, the 44-year-old founder of a mobile health app start-up, died suddenly of a heart attack. Chinese media reports linked his death to his punishing routine of working late into the night — often still sending emails at 3am.

“Manufacturing sector working hours are declining: you are not seeing the same level of excessive overtime that you used to,” says Geoffrey Crothall, a spokesman for Hong Kong-based charity China Labour Bulletin. He cites falling demand for manufacturing labour in the country as it transitions to a more service-based economy. But, he adds, “in white-collar jobs, working hours continue to escalate”.

Tech companies are leading the trend. In 2016, Didi Chuxing, China’s biggest ride-hailing platform, investigated urban white-collar overwork, based on taxi bookings from business buildings to residential areas between 9pm and midnight on working days. Its data showed that employees of internet, finance and media companies were most likely to be working late into the night.

There is strong evidence linking long hours to poor health. People who work for more than 55 hours a week face an increased risk of stroke and coronary heart disease compared with those who work between 35 and 40 hours a week, according to a study based on data from more than 600,000 individuals, published in 2015 in The Lancet medical journal.

A survey in Shanghai last year of patients with cardiovascular disease found a significant incidence of arrhythmia — an irregular heartbeat that can be a prelude to more serious disease — in patients aged 21 to 30. Sun Baogui, executive vice-chairman of the Chinese Heart Failure Society, says this finding was consistent with their reported lifestyle of long working hours and getting little sleep. Some 85 per cent of white-collar workers in China have to work overtime, with more than 45 per cent reporting overtime of more than 10 hours a week, according to a survey last year by job recruitment website Zhaopin.

China is not the only country in the region where long working hours have become a cause for concern. Karoshi , as death from overwork is called in Japan, has become a recognisable phenomenon across east Asia, according to an academic paper published in 2014 — although China appears to have lagged behind neighbouring countries such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan in providing proper recognition and compensation for bereaved families.

Mental health is another risk. Working long hours is associated with depression and anxiety, which can lead to disturbed sleep and worse. A national health and wellness survey in 2017 by Kantar Health, a consulting firm, found that nearly 20 per cent of adults in China who worked more than 51 hours a week reported feelings of anxiety.

Employees of technology companies who spoke to the FT said they expected a long-hours culture when they entered the industry. However, although Chinese law requires overtime work to be compensated at 1.5 times ordinary pay, they said they did not generally receive such payment, because the work was classified as “voluntary”, meaning it falls outside the official definition of overtime. A Chinese lawyer, who wishes to remain anonymous, says there is no mechanism to protect employees’ rights if they have agreed to “voluntary overwork”.

The lines between voluntary and enforced overtime are often unclear. “[When supervisors] tell you to attend a meeting, or prepare materials, can you say no?” says Huawei’s Li. She says that in her experience much of the overtime work she feels she has to do is a result of inefficient management. Working in a support role, she often has to wait for signatures from different levels of the company bureaucracy. “Extreme cases were 10-20 signatures,” she says. Huawei and Tencent declined to comment for this article.

Some companies, however, are trying to change the overwork culture. Feng Dahui, founder and chief executive of Nocode Technology, a medical research engine start-up, says mental work requires creativity and “overwork does not achieve better results”. His employees usually start work at 10am and finish by 7pm, he says.

Watched at work: the rise of surveillance technology

In a high school classroom in the eastern Chinese city of Hangzhou, students listen in rapt attention to their teacher. Everything seems normal, except for the cameras mounted high on the walls. These are part of a network of facial-recognition cameras and software that track everything from students’ daily nutritional intake to their engagement in the classroom, writes Emily Feng.

“What else can surveillance cameras do in a classroom other than exam supervision?” asked the People’s Daily, the Communist party organ, in what appeared to be an approving post on Twitter.

Yet free speech advocates say that in the long run, increased surveillance will impair learning. “Surveillance in educational institutions will have a chilling effect on speech and thought,” says Lokman Tsui, an assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s journalism school. “Surveillance of these spaces will have a negative impact on the trust between the institution and students, between students themselves and, more generally, negatively impact learning and the exchange of ideas.”

Artificial intelligence-based surveillance technology is being used increasingly in the Chinese workplace, too. At Chinese search engine company Baidu, for example, employees enter and exit the company’s gleaming Beijing headquarters through facial-recognition turnstiles.

Psychological studies in the US have found that employees in jobs where they were electronically monitored reported increased levels of stress.

While some fear this type of technology will be used as a tool in China’s crackdown on dissent, it also provides a futuristic upgrade to a nationwide system of monitoring citizens — including the controversial construction of a social credit system — that could have distinct effects on their mental health.

In Xinjiang, in China’s far north-west, a modern-day surveillance state has emerged. Security checkpoints equipped with facial recognition cameras dot the landscape. Targeted individuals have been required to submit voice and face scans in addition to DNA samples. For those people, the risk of stress from surveillance has already become a reality.

Employees’ names have been changed at their request.

This story has been amended to reflect the correct name of the Hong Kong-based charity as China Labour Bulletin

Comments