‘I am close to quitting my career’: Mothers step back at work to cope with pandemic parenting

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Maya was on maternity leave when the pandemic struck, but within months of returning to work in July, the London-based IT consultant and mother of two young children was at the end of her tether.

She took a few weeks’ leave and cut back her hours, but continued to struggle. “I feel I am at the verge of breaking and very close to quitting my career,” she told the Financial Times.

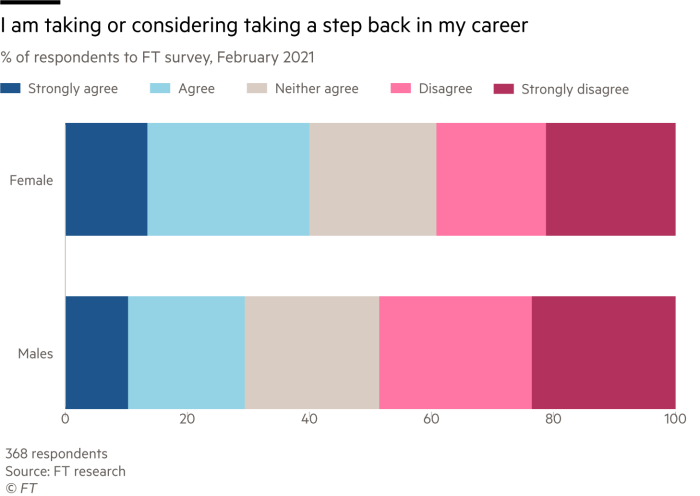

A global survey of FT readers indicates that she is far from alone. As the pandemic forces parents into an impossible juggling act between career and childcare, two in five working mothers have taken, or are considering taking, a step back at work, the survey found.

The proportion of fathers looking to reduce their workloads was 10 percentage points lower among the nearly 400 respondents, who responded in the second half of February.

Olivia, not her real name, resigned from her role as a product director to look after her three children so that her husband could protect his higher paying job. Jo, a mother of two, took voluntary redundancy from her position as chief operating officer after suffering a breakdown. “I think years of movement forwards for working women is going to be undone by this,” she said.

The findings add to mounting evidence that the pandemic has disproportionately affected working women because of school closures and their over-representation in precarious jobs — and could increase gender disparities long after it ends.

While the majority of respondents were in the UK and US, others shared their views from Europe, India, Nigeria and Asia-Pacific. Many did not want to share their full names or personal details for fear of professional repercussions.

Globally, 90 per cent of schoolchildren faced shutdowns at the peak of the Covid-19 disruptions, leaving family members to care for them at home for much of the year, according to the UN.

Francesca Caselli, economist at the IMF, warns “of a possible widening of gender inequality, as women may compromise their employment opportunities if they have to stay at home to care for children”.

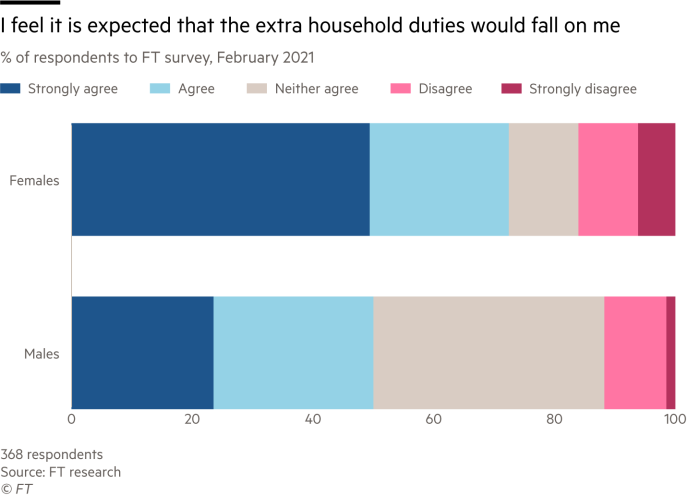

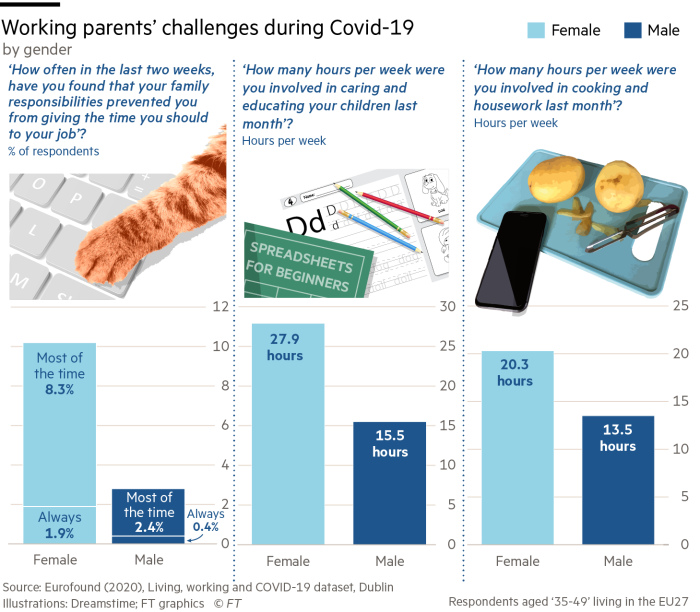

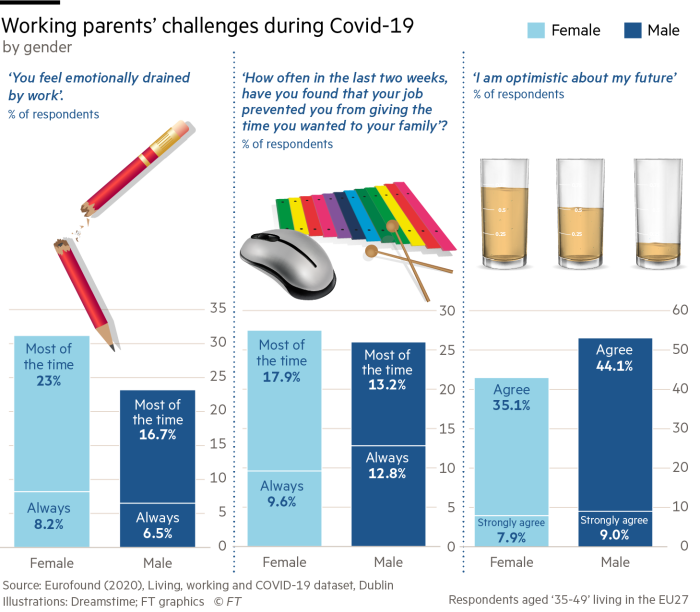

While many fathers have become more involved in household responsibilities, the division of household labour during the crisis has largely fallen back on old patterns. Senior-level women were 1.5 times more likely than men to think about downshifting their careers or leaving the workforce because of Covid-19, according to a McKinsey report.

“As a mom, there’s the unspoken expectation that I’m supposed to be the one doing the educating, even though I’m the main breadwinner,” said Faith, a mother working in the tech industry in the US.

‘My ability to participate in the workplace has gone back to the 1950s’

The gender imbalance in childcare and housework partially reflects the fact that women are more likely to be in temporary, part-time or lower-paid work than male partners, according to Monika Queisser, head of the social policy division at the OECD.

Beth, a director of technology in the UK’s healthcare sector, took indefinite leave from her job to care for her two children despite being at the same level of seniority at work as her partner. “We had to prioritise my husband’s role as he . . . gets a greater salary,” she said. “As a female I feel [the pandemic] has taken my ability to participate in the workplace back to the 1950s.”

Across the more than 30 countries of the OECD, over 25 per cent of female workers were in part-time jobs before the pandemic, more than twice the share of men. The proportion of women in low-paying jobs was also much higher, and they were over-represented in hard-hit sectors like retailing.

While the main burden of childcare has been laid on mothers, many fathers have stepped up at home. The FT survey showed that two in five men reported doing more household work, in line with a German study that found that fathers increased childcare time during lockdowns.

This could “point to a more positive outlook in the household’s division of housework” in the long run, Queisser said.

“I’ve worked in a male-dominated industry for 15 years and, finally, my male colleagues mention their children at work. This is a huge positive,” said Sally from Lausanne, Switzerland.

Some parents are questioning ever returning to their pre-pandemic arrangements. “My work contribution has not been great this past year [but] we spend more time together, we have a more equal share of housework . . . to the point where I wonder if we can go back to the life before,” said a male consultant in the UK and a father of three.

Despite this, women still do the majority of housework and home-schooling.

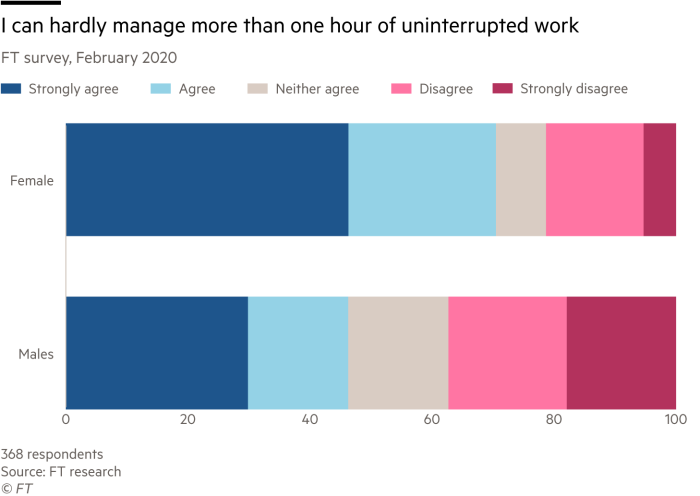

More than 70 per cent of mothers said in the FT’s survey that they felt it was expected that extra household duties would fall on them. A similar proportion of women report hardly managing more than one hour of uninterrupted work, 24 percentage points more than men.

“My children are stuck to my hip all day, which means I am constantly interrupted at work, and [they] rely on me for everything from comfort to explaining their school work,” said Adie, a mother of two primary school-aged children in a senior role in wealth management.

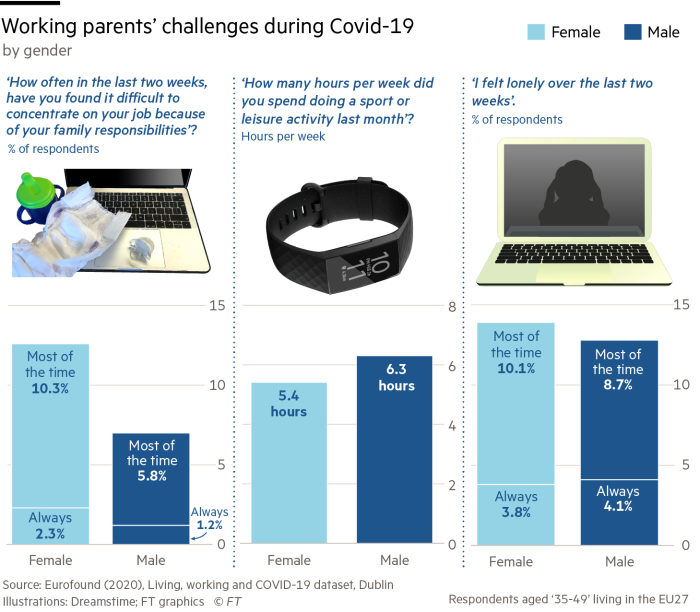

Women aged 35 to 49 were involved with about double the childcare hours than men in July and August, according to an EU-wide survey. A similar difference was reported for cooking and housework.

Constance, a mother of two who works in communications in the UK, lost her job during the pandemic. She said that the company was thriving “but they knew they could not get their pound of flesh from a highly paid exec who . . . would also be distracted by children and home schooling”.

‘My experience has been a living nightmare’

Most countries provided some sort of support to working parents during the pandemic, such as subsidised family leave in Japan, Korea, France, Germany and Italy, or childcare provisions in Costa Rica and the UK.

But parents said it was not nearly enough. The government has “sacrificed us and our children”, said a female lawyer with three children. “We simply cannot work and attempt to supervise our children. At times we have all felt huge despair in this house.”

“I have no support from the government, nor from my employer. I feel that I just have to carry on doing the best I possibly can to keep us sane,” said Carolina, a single mum working in the public sector in Portugal.

Only 2 per cent of an estimated $10.8tn global Covid-19 response during the first wave went to family-specific social policies, leaving “a disproportionate burden . . . on women”, according to Anna Gromada, a social and economic policy consultant at Unicef.

Countries that did better, such as in Scandinavia or the Netherlands, already had strong family policies before the pandemic, including high-quality part-time jobs and extensive parental leaves, according to Heejung Chung, a researcher at Kent university.

In countries like the US and UK with cultures of long working hours and little government planning to help parents cope, the challenge for working parents was exacerbated. “I am concerned about the direction of travel that we are seeing” on gender balance, she added.

Mental health has suffered as a consequence. Nearly nine in 10 respondents to the FT survey reported higher levels of stress, with an even higher proportion among women. The vast majority reported lower levels of motivation and happiness.

Women at the Top 2021

Reset and Rise

The pandemic has been the ultimate workplace disruptor, but it is also a chance to reset work cultures and fix the most persistent barriers holding women back from reaching the top ranks of business. How could a diverse workforce help to speed up recovery? How can women rise – and thrive – in the new world of work?

Join the debate at our live events:

Women at the Top Europe, October 20-21

Women at the Top Americas, December 15-16

“It’s been the toughest year of my life,” said Laura, a consultant from New York with three children of elementary school age. “I am losing my mind. I’ve gained 30 pounds and I’m miserable.”

UK official statistics showed that during the lockdown, levels of happiness across the population fell at a double-digit rate, while anxiety rose. Parents scored worse on both counts than non-parents.

“My nine-year-old son is suffering badly from not being in school . . . His behaviour has deteriorated and he acts like a four-year-old with temper tantrums and an obsession with his Nintendo games,” said a female accountant from the UK. “My experience has been a living nightmare.”

Comments