Arts: What to watch out for in 2016

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

JAZZ

Cécile McLorin Salvant

Cécile McLorin Salvant isn’t the only jazz singer to deliver knowing songbook re-makes and to reference the great vocalists of the past. But few pirouette from style to style with her panache or match the Miami-born 26-year-old’s repertoire and range. She moans and growls the classic blues of Bessie Smith, tiptoes through obscure ragtime ditties and stamps chanson with the authenticity of her French-speaking roots — her father is Haitian and her mother French. Lyrics are delivered with such theatrical relish that even the flimsiest gain narrative weight. Classically trained, she started to perform jazz only in 2007, after moving to France. Three years later she won the Thelonius Monk Institute International Jazz Competition. She debuted in the UK at Ronnie Scott’s in 2014 and sold out a show during this year’s London Jazz Festival. Her third CD, For One to Love, confirms her potential to be the outstanding jazz vocalist of her generation.

Mike Hobart

VISUAL ARTS

Francisco Vidal

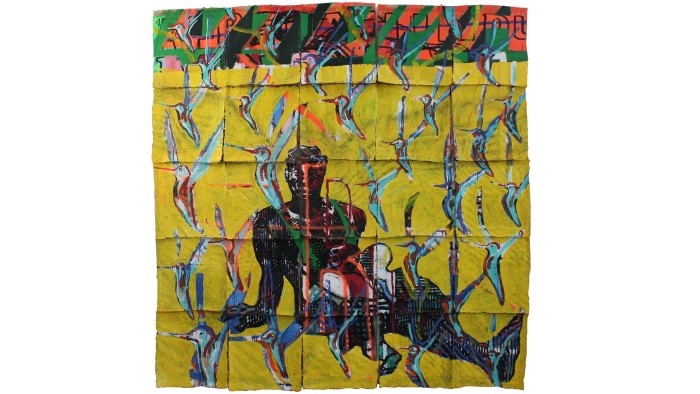

Francisco Vidal paints brilliantly coloured cotton flowers directly on to metal machetes traditionally used to harvest cotton — a reference to the 1961 Malanje plantation uprising which sparked Angola’s war of independence. He is also a master of decorative pattern, abstracting motifs under colour blocks interspersed with calligraphic lines.

But Vidal, born 1978 and working between Luanda and Lisbon, is more than an expressive painter. Like many innovators, he furthers collaboration — he co-founded the collective e-studio Luanda, which represented Angola at last year’s Venice Biennale. His first London exhibition, Workshop Maianga Mutamba, took place at Tiwani Contemporary at the end of 2015; he will have a solo presentation at New York’s Armory Show in March.

Jackie Wullschlager

WORLD MUSIC

Lula Pena

This Portuguese singer’s admirers are always trying to convert unbelievers. Although she plays regularly — she accompanies her own arresting alto on Portuguese guitar, often joined by a Guinea-Bissauan multi-instrumentalist or a New Zealander saxophonist — she records rarely: there was a 12-year gap between her first record, Phados, and her second, Troubadour, and that was six years ago. But for 2016 she has signed up with celebrated Brussels label Crammed for an as-yet untitled third.

That first album title notwithstanding, her music is not really Fado but an eclectic bricolage of Atlantic crossings and recrossings: everything from Arabic poetry and 1970s Americana, including nods to Caetano Veloso’s Tropicalismo and French chanson. She deserves to be much better known; the new album should finally raise her profile.

David Honigmann

THEATRE

Alistair McDowall

When this young British playwright’s Pomonaopened at the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond, Surrey, in 2014, it caused shockwaves. Here was a venue not readily associated with the wilder shores of innovation but Pomona was a strange, experimental piece. A year later the slippery dystopian thriller transferred to the National Theatre’s temporary space in London.

McDowall’s boldness lies partly in his willingness to mix social issues withideas drawn from graphic novels, game culture or cult films. Pomona’s starting point was a real strip of wasteland in Manchester but it spiralled in and out of fantasy territory. For his next major piece he is off into space: X, staged in March at London’s Royal Court, considers a future in which a research group has been abandoned on Pluto. What might that do to a person? If anyone can imagine it, McDowall can.

Sarah Hemming

FILM

Ryan Coogler

Safe hands are rarely idle in the film business, but in Creed, the latest installment of the Rocky saga, 29-year-old director Ryan Coogler has proved himself far more than just a reliable journeyman. The film is vivid, fresh, unexpectedly stirring. Its excellence should not have been a surprise: Coogler’s debut Fruitvale Station was a potent account of the 2009 killing of the young African-American Oscar Grant by transit police in Oakland, California. Now, two films into his career, Coogler looks set for the long-term: a big-league presence with his own distinctive voice, and a beacon for black filmmakers.

Danny Leigh

DANCE

Dancers and choreographers

Herewith a message in a bottle for dance-lovers. The coming year could do worse than bring us creations from three astute, intriguing and gifted choreographers: Canada’s subtle, elegant, imaginative Crystal Pite; New York City Ballet’s Justin Peck, who turns music into dance with an unstressed felicity; and Britain’s own Alexander Whitley, whose imagery is always intriguing and concerned with bodies in motion.

As for dancers: the Bolshoi Ballet’s summer season in London should bring Olga Smirnova, whose every action touches the sublime, and the young and Apollonian classicist Artem Ovcharenko. The Royal Ballet’s Vadim Muntagirov provides a similar example of classical dancing that is unalloyed and life-enhancing. And, for the Royal Ballet’s Laura Morera and Bennet Gartside, the hope that they will continue grandly to illuminate every role they perform.

Clement Crisp

THEATRE

Thom Southerland

He’s hardly a newcomer. Thom Southerland’s production of Titanic won both the WhatsOnStage and Off West End Awards for Best Production and transferred to Tokyo and Toronto in 2015. He has shown an uncanny skill at animating musicals in small spaces, often the Union Theatre beneath the railway arches of Southwark. His resumé runs from a brace of the Union’s all-male Gilbert & Sullivan revivals (HMS Pinafore and The Mikado) to lesser-known works by prominent writers such as Jerry Herman’s The Grand Tour and Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Me and Juliet. In January he stages the European premiere of the stage musical version of the Maysles brothers’ documentary film Grey Gardens; it can’t be long before he is unleashed on the West End.

Ian Shuttleworth

POP

Loyle Carner

Loyle Carner grew up on grime, London’s take on rap music, but has turned into a different kind of rapper. The 20-year-old drama school dropout has a softly spoken flow, older-sounding than his age and set to a slower beat than grime’s hyperactive motions. The set-up focuses our attention on the words, and they repay it. “Cantona”, about his stepfather’s death, contrasts a mournful looped sample with Carner’s busy weave of memories and thoughts: life goes on. “Tierney Terrace” uses an old-school drumbeat to recount a portrait of family life that grows more complex with each bar he raps.

Among his models are hip-hop golden-age greats A Tribe Called Quest and performance poet-turned-rapper Kate Tempest, with whom he collaborated on the track “Guts”. If his debut album keeps up the quality — and Carner’s measured demeanour suggests it should — then UK rap will have a new name to conjure with.

Ludovic Hunter-Tilney

FILM

Wave rules Britannia

The French New Wave, the starter mechanism for modern cinema, changed the way we see and appraise cinema itself. Sixty years on, bits of it are still to be found under every filmmaker’s car bonnet. (Even Tarantino’s. He named his film company A Band Apart after a Godard movie.) Britain’s BFI Southbank starts 2016 with a Godard retrospective, its showpiece a revival run of Le Mépris (1963). Brigitte Bardot, Jack Palance, Fritz Lang — who else got casts like that in the penurious prime of European art cinema? In spring/summer we get Kent Jones’s praised documentary Hitchcock/Truffaut, strewn with soundbites from Wes Anderson, Peter Bogdanovich, David Fincher. Hitch may have been a genius, but it took Truffaut, interviewing the master, to press that truth on the world. (In the year’s second half, hold your breath, we might get Godard’s new film, progressing as we speak.)

Nigel Andrews

VISUAL ART

Nasreen Mohamedi

In March 2016, the Metropolitan Museum will inaugurate their new Breuer building with an exhibition of work by Nasreen Mohamedi. It should propel the Indian abstractionist into the global spotlight after too long as the best-kept secret of connoisseurs of south Asian art. Steeped in Zen and Sufi, influenced by Indian abstractionists such as V.S. Gaitonde as well as western modernists including Mondrian and Malevich, Mohamedi’s starting point was the grid. Her tools were pencil, pen and paper. Yet her frail, monochrome geometries possess a charisma that few oil paintings can rival.

By her death in 1990, her shapes had taken flight into transcendence. Ellipses, triangles and chevrons soar across the page in silky blacks and diaphanous whites. Buoyed by cosmic energy, they fulfil Mohamedi’s ambition to “break the cycle of seeing [so that] magic and awareness arrives.” This exhibition should see Mohamedi (who died in 1990) recognised as one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.

Rachel Spence

OPERA

Thomas Adès

It is 13 years since Thomas Adès’s last opera. Expectations have been mounting ever since and the suspense will at last be broken this summer when The Exterminating Angel has its premiere at the Salzburg Festival, the latest in Salzburg’s series of new operas by major composers. The Exterminating Angel is based on the film of the same name by Luis Buñuel. Adès says he was attracted by the film’s almost surreal territory, in which people are “trapped inside their own heads”, and a priority will be creating “emotional atmosphere”.

With a cast of nine this also promises to be a true ensemble opera. Adès’s name should take it far. Unlike so many contemporary operas, which struggle to get repeat performances, The Exterminating Angel — a joint commission from Salzburg, London, New York and Copenhagen — sets out with a full diary, even before it has been seen.

Richard Fairman

Nadine Sierra

Born in 1988, soprano Nadine Sierra is embarked on what promises to be an impressive opera career. She commands a remarkably wide vocal and emotional range, and utilises both to enhance dramatic pathos as well as sonic glitter. She made her Met debut as Gilda in the company’s controversial Vegas-style Rigoletto earlier this month.

The same challenge marks her La Scala debut in January, and in June she impersonates Tytania in Britten’s Midsummer Night’s Dream in Valencia. The American lyric-coloratura is a graduate of numerous vital US training programmes; at Marilyn Horne’s Music Academy of the West she was the youngest student ever to earn the prime Foundation honour. In 2011 she became an Adler Fellow at the San Francisco Opera. She also appeared with the Gotham Chamber Opera in Xavier Montsalvatge’s El gato con botas.

Martin Bernheimer

DANCE

Michelle Dorrance

Just when tap dance seemed to have given up permanently on Astaire elegance and kaleidoscopic Busby Berkeley formations, one-time Stomp trouper Michelle Dorrance conceived a show that had it all. Last year’s The Blues Project treated us to long-limbed panache, visually exhilarating group choreography and the filigreed yet full music that Noise/Funk star Savion Glover resurrected for the hip-hop era from a long line of forgotten black hoofers.

The newly minted MacArthur “Genius” also proved her experimental mettle, setting the work to blues-based roots rock. Not an obvious choice for tap but a compelling one. Expect more startling moves in April at the Joyce Theater, when Dorrance and company join forces with break dancer Ephrat “Bounce” Asherie and electronic tap innovator Nicholas Van Young.

Apollinaire Scherr

Comments