From peak city to ghost town: the urban centres hit hardest by Covid-19

Simply sign up to the Coronavirus economic impact myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The few people on the streets of the City of London or lower Manhattan have got used to a familiar sight in recent months: empty shops, boarded up storefronts and cafés struggling for survival in once bustling financial districts.

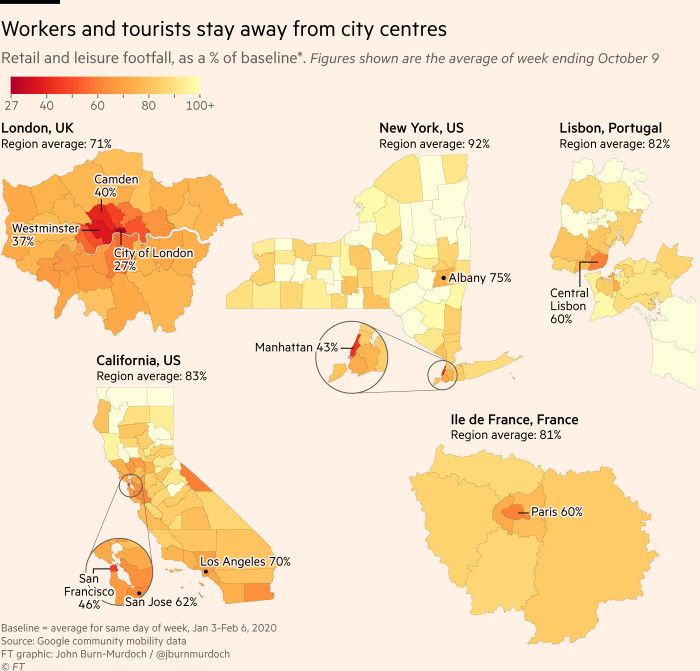

Their eyes do not lie — city centres have become ghost towns. According to FT research which analysed Google mobility data, London and New York have seen a dramatic drop in visits to restaurants and retail venues since the start of the pandemic.

Few cities have escaped the impact. Visits to central Paris were down 40 per cent in the week to October 9 compared with the pre-pandemic average in January, and even Stockholm, which has had much lighter restrictions, has suffered a decline of 20 per cent.

But it is cities like New York and London, where high-rise office buildings host a large number of professional services and banking staff now mostly working from home, which have suffered the most.

In the City of London, the number of people visiting cafés, restaurants and retailers in the first week of October was less than one-third that of pre-pandemic levels — with some of the gains over the summer lost in recent weeks as the UK fights a second wave of coronavirus infections.

That stark figure shows that the City has been substantially more depressed than the UK as a whole, where visits to restaurants and entertainment venues were just above 70 per cent that of pre-pandemic levels.

In Manhattan, the number of visits to amenities was less than half that of pre-pandemic levels, compared with 85 per cent for the national average, with similar depressed levels seen in the technology hub of San Francisco.

These are the most startling results of a comprehensive FT analysis of Google mobility data for city centres and other areas across advanced economies and large developing countries for which data is available. Google does not track mobility for China.

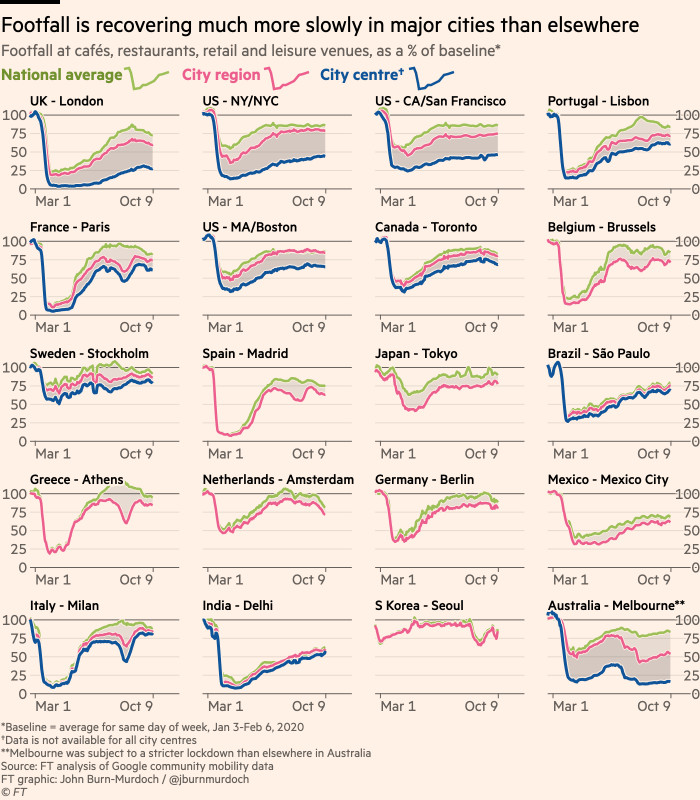

In major urban areas, from Boston and Milan to Tokyo and Mexico City to New Delhi and Toronto, city centres show larger falls in mobility.

Footfall in most cities and countries have been recovering since the lockdown lows, but the latest data show the trend reversing in some countries as restrictions have been tightened in response to a rise in coronavirus cases.

Since lockdowns were first implemented in most countries around the world, urban experts have speculated about the long-term impact on city centres whose economic success is largely based on the agglomeration of a skilled workforce with disposable income.

With a vaccine yet to be approved and with many governments reintroducing tighter restrictions, many experts say some changes in the way cities are organised will start to become permanent. They believe that Covid-19 could accelerate the pull of the suburbs for families and shift more jobs out of city centres.

“The pandemic will not only reshape cities but it’s going to reshape suburbs and rural areas,” says Richard Florida, a professor at the University of Toronto's School of Cities and Rotman School of Management and a distinguished visiting fellow at New York University’s Schack Institute of Real Estate.

Suburban drift

Falling office demand and drying up investment are signs that the shift towards a more diffuse urban landscape could have already started.

“Some of that work will be shifted out to more remote locations in the suburbs and rural areas,” Mr Florida says. “It’s clear that we can rebalance work so that not everyone has to go into the central business district all the time.”

Homeworking has rapidly eroded the need to fill large towers with office and knowledge workers, which Mr Florida refers to as the “last gasp of the industrial revolution”. Instead, it has created the possibility for businesses to consider smaller units or less expensive locations.

Nicholas Bloom, a professor of economics at Stanford University, says the pandemic has already transformed the US into a “working from home economy”, with almost twice as many employees working from home as at the office.

As nearly 60 per cent of those now working from home were based in cities, according to a Stanford survey, he believes the trend could mark the reversal of the fast growth of the largest US cities since the 1980s.

Across Europe, nearly 40 per cent of employees worked remotely in the first half of the year, according to the European Commission. In Germany, the labour ministry has announced that it will present a proposal this autumn that would provide all employees with an enforceable right to work from home.

About three-quarters of British businesses say they will keep increased homeworking in place after coronavirus has been suppressed, according to a survey run by the Institute of Directors, a UK business organisation.

Real estate data suggest that widespread homeworking resulted in an immediate shift in demand.

About 60 per cent of global surveyors indicated a shift in office space from urban to suburban locations, according to the latest commercial study by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, while about 50 per cent indicated that the footprint of the office would be scaled back over the next two years by up to 10 per cent.

Global commercial property prices are down 6 per cent in the third quarter compared with the same period last year, according to Adam Slater, lead economist at Oxford Economics. “It’s possible that demand for office, retail and hotel space, and even urban multifamily housing may never recover to pre-crisis levels.”

Jeremy Kelly, director of global research at the real estate advisory group JLL, sees a similar fall in investment. The company reports a contraction in leased office space of 59 per cent for London, 66 per cent for New York and 77 per cent for Tokyo in the second quarter of this year, compared with the same period in 2019.

He thinks that demand will “bounce back eventually”, but with lower density and “more space for innovation, face-to-face interaction and more meeting space”. He adds: “There could be more people travelling to urban cores but perhaps less frequently.”

Joel Kotkin, a fellow in urban studies at Chapman University in Orange, California, believes that with the impact of Covid-19 the role of cities “will be diminished”.

With suburbs able to offer improved jobs and learning opportunities as well as services, he believes urban centres “are not going to be the place of aspiration they used to be”, while “suburbs will become more interesting over time”.

The “next phase of urbanism will be dispersed and with lower density”, Mr Kotkin says, adding that young people will still flock to cities as they will continue to be the best place to start a career. But “people who would have stayed in the cities until 35 would leave at 30”.

Smarter centres

Many urban areas are preparing for big changes. Paris is championing the concept of the “15-minute city”, where living spaces are a short commute from work and amenities; Melbourne is proposing “20-minute neighbourhoods”; Montreal is working on defining a hybrid system that combines remote working and the continued use of physical space.

“The pandemic is changing the city in . . . lasting ways,” says Thomas J Campanella, an associate professor of urban studies and city planning at Cornell University, New York. “Firms will downsize to small flexible workplaces with conference rooms and hot desks where employees can collaborate face to face as needed,” he says, while “new forms of shared facilities will crop up in neighbourhoods and suburban centres”.

However, the possible rebalancing of work to suburban areas could be the chance to make city centres greener and possibly more lively, some experts argue.

“There is a momentum today,” says Lamia Kamal-Chaoui, director at the centre for regions and cities at the Paris-based OECD. “Many major cities have already started to engage in a complete rethinking of their urban planning, their overall recovery strategy in light of life with Covid-19.”

Some cities are “seizing this opportunity to go more inclusive . . . more green . . . and more digital”, she says, adding that the suburbanisation trend seen in some OECD countries before the pandemic could now “accelerate”.

Cities such as Paris, Montreal, and London have already taken measures such as including additional bike lanes, better hygiene on public transport, such as contactless fare payments, and encouraging low-emission transport options, such as electric vehicles and scooters. This is true also for many cities in developing countries, including new bike lanes in Chennai, India, and more investment into smart and green cities in China.

Mr Florida envisages future cities with offices converted into affordable housing, less space for cars in the streets and more for outside dining and other social activities. “I think health and resilience will become part of the design of cities generally,” he says.

Edward Glaeser, an economics professor at Harvard University, says the debate in the US has sometimes focused on urban problems that have been exacerbated by the pandemic, such as violence and falling tax revenues.

“What I have seen is a huge amount of debate around rioting and policing — not about bike lanes,” says Mr Glaeser. “In the US, we are going to have fiscal problems in our cities that are going to be persistent for many years.”

Although coronavirus will continue to weigh on commercial activity in the near term, he is “optimistic” about the future of cities. Their attraction will not vanish because “there are huge losses not being face to face” and because people continue to want to have human interaction.

Moreover, falling commercial and residential property prices might make cities more lively, with “younger and scrappier firms more willing to go back” and “older people moving out as younger people move in”.

If the crisis makes it easier for younger people to live in city centres, it could end up being the spark for their renewal, not the start of their decline.

Latest coronavirus news

Follow FT's live coverage and analysis of the global pandemic and the rapidly evolving economic crisis here.

Comments