How the Ukraine war could boost China’s global finance ambitions

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

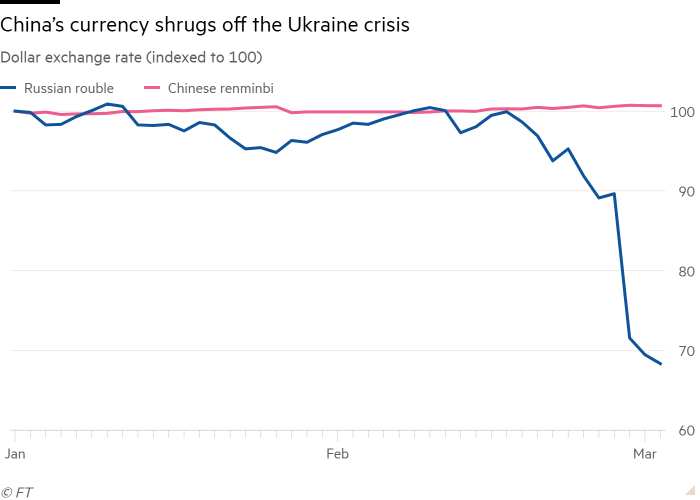

Sanctions levied in response to Russian president Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine have dealt a devastating blow to his country’s financial system and left the rouble down more than 30 per cent this year, sending ripples across currencies in eastern Europe.

But the renminbi, the currency of Russia’s closest strategic ally and top trading partner, has remained conspicuously stable.

China’s currency has barely budged since Russia’s invasion began, even touching a four-year high of about Rmb6.31 against the dollar, extending a months-long run of resilience despite a recent slowdown in the growth of China’s economy.

Its relative stability has fuelled talk that the currency could become a haven asset, shielded from the geopolitical turbulence that has roiled markets around the world. This would be a boost to more than 20 years of work by Beijing to globalise its currency by increasing its use in foreign trade and as a store of value in international finance.

“We are in a stage where the market is no longer looking at the renminbi as a highly speculative currency,” said Kelvin Lau, senior economist for Greater China at Standard Chartered, adding that its recent stability was likely to enhance its reputation as a haven in times of stress.

What does this have to do with the dollar and the wider financial system?

Wider usage of the renminbi across the globe would, theoretically, make it easier for China to break what it views as US and western dominance in global payments and finance — power that has been wielded in recent days to punish Russia.

There are signs of progress: in recent months, the Chinese currency finally pipped Japan’s yen in Swift’s international payments rankings to take fourth place for the first time. Meanwhile, a renminbi globalisation index published by Standard Chartered showed its global standing has surged to a record high.

But China’s real ambition is to move beyond dependence on western-controlled financial infrastructure such as Swift, from which Russia has been partially excluded. That is why it has spent years building out its renminbi-denominated Cross-Border Interbank Payments System (Cips), through which payments rose about 20 per cent to Rmb45.2tn ($7.1tn) in 2020.

Cips has about 1,200 member institutions across 100 countries and remains a relative lightweight in international payments compared with Swift, which has about 11,000 members. But Russia’s own cross-border clearing system is far less developed, with about 330 institutions signed up across far fewer markets including Cuba, Armenia, Kazakhstan and Iran.

Chinese media have flagged the opportunity presented by the Swift ejections, with state news agency Xinhua noting that “Russian financial institutions kicked out of Swift may have to participate in China’s Cips” in light of the limited use of Russia’s homegrown clearing system.

And as payment networks Visa, Mastercard and American Express have announced plans to suspend operations in Russia, more of the country’s banks have also floated the possibility of issuing co-badged cards linked to both Russia’s Mir and China’s UnionPay international payments systems.

Benjamin Cohen, a veteran academic of international monetary relations, said there was “no question” sanctions against Russia would further incentivise countries such as Iran, North Korea and Venezuela to diversify away from the dollar.

“Every time the US and its allies make access to the dollar a weapon, it creates an additional incentive for the Chinese to take advantage at some point,” said Cohen. “It’s not a case of the Chinese wolf at the door [of US dollar hegemony], it’s more a case of termites in the woodwork.”

This is in keeping with China’s longstanding ambitions.

“The events of the past few days will give a fillip to those countries and institutions that want to bypass the dollar-based international financial system,” said Eswar Prasad, economist and former head of the IMF’s China division.

Why does China want to internationalise the renminbi?

Beijing’s desire for a global currency on a par with the dollar is decades old but was reinvigorated in the early 2010s when US sanctions on Iran highlighted China’s own vulnerability to systemic financial punishment by western powers.

China launched Cips as a renminbi-based rival to Swift in 2015, after Russia was hit with sanctions over its invasion of Crimea the previous year.

“Only after the crisis in Crimea did China accelerate the pace of renminbi internationalisation,” said Bruce Pang, head of research at China Renaissance.

That greater openness backfired in 2015, when a one-off devaluation of the renminbi by China’s central bank spurred unprecedented capital flight and a protracted fall for the currency. The rout ended only when Beijing enacted hard capital controls that remain largely in place.

Tommy Wu, chief China economist at Oxford Economics, said Beijing had learned from its mistakes but would feel renewed pressure to boost the currency’s global role following recent sanctions against Russia.

“Beijing will have more of a sense of urgency now,” said Wu. “But they still have to look at what happened in the past and what they can actually do realistically.”

How much is the renminbi already woven into Russia?

Since Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, China has been exceptional among leading global economies in abstaining from sanctions or even direct criticism. That is because much is at stake on both sides maintaining cordial Sino-Russian relations.

Russia is an important supplier of oil and natural gas to China, and Moscow and Beijing have made removing the US dollar from their trade settlements a priority since 2014, in response to blowback from the west to Russia’s invasion of Crimea. The two countries’ central banks signed a currency swap agreement that year, and it was recently renewed for Rmb150bn.

By the first quarter of 2020, the greenback’s share of Sino-Russian trade had fallen below 50 per cent for the first time, according to Russia’s central bank, while the rouble and renminbi’s combined share of settlements had risen to about a quarter.

That is a large and growing sum: bilateral trade rose more than a third to almost $150bn last year, according to Chinese customs. In February, the two countries pledged to boost the total to $250bn while Putin was visiting Beijing for the Winter Olympics, where he revealed new oil and gas deals with China worth more than $117bn.

The renminbi also occupies a large chunk of Russian foreign reserves thanks partly to a 2019 agreement allowing China to buy Russian gas in its own currency. A January report from Russia’s central bank showed renminbi assets worth $73bn at 13 per cent of total reserves.

How far might China go to support Russia?

Analysts say the scope of sanctions on Russia so far could allow China to use its renminbi-based payments infrastructure to help circumvent measures meant to cut off Moscow from global finance.

Chinese banks with an international presence were unlikely to rush to Russia’s aid, said Wu, but smaller domestic lenders not reliant on dollar-dominated western finance could provide renminbi services and Russian institutions could conceivably route global transactions through China’s sprawling state-run policy banks.

However, Pang said that concerns over severe retaliation from western countries — including possible sanctions on China itself — would seriously limit Chinese financial institutions’ ability to offer more substantial support to Russia.

“That’s why China’s top financial institutions have complied with previous US sanctions on Iran and Russia,” he said. “China has to carefully manage the pace of doing this and not give western countries any excuses for sanctions, bans or boycotts.”

Comments