Amanda Levete: the architect building the future

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

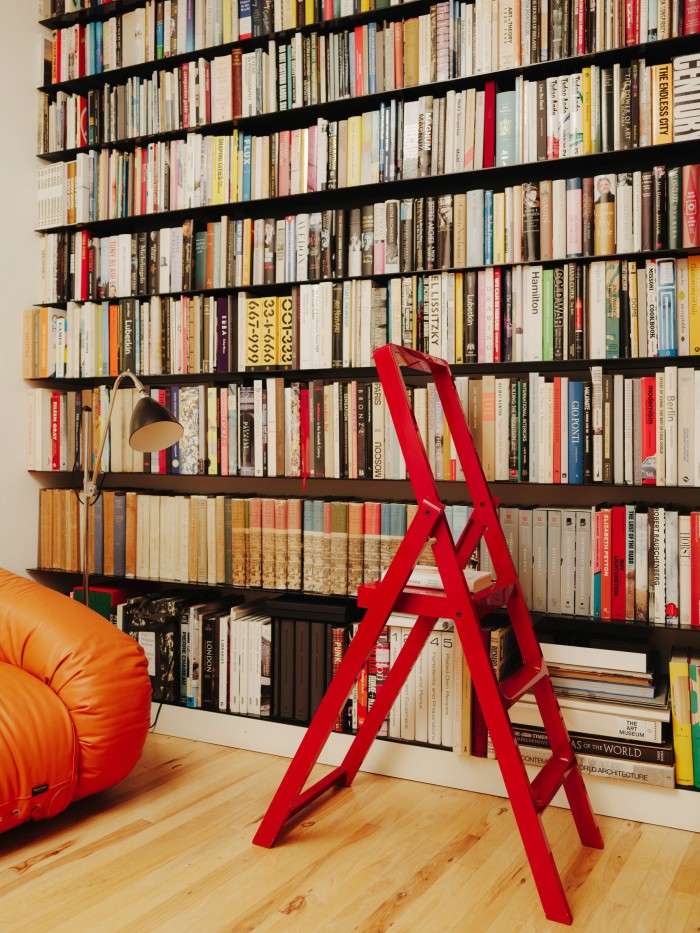

London. Architect Amanda Levete opens the door to her Islington home and leads the way into her library-office. Sun streams through the open window, pooling light over rows of books that are stacked from floor to ceiling at the far end of the room. It’s an eclectic hoard. Tony Blair hangs out with Vivienne Westwood and Hogarth amid compendiums on design and architecture. On the top row, The Catcher in the Rye shares shelf space with The Girl on the Train.

It’s a distillation of the interests of a family. Ben Evans, Levete’s husband, is director of the London Design Festival and co-founder of the city’s Design Biennale; and until recently the couple shared their home with four now-grown children.

Levete, of course, has worked her architectural magic on the period terrace house, which appears like any other from the street but is Tardis-like inside, opening into a glass-punctured living space of epic proportions. “It’s a really big social space,” she says. “Four years ago, for my 60th birthday, we had a sit-down dinner for 110 people.”

The architect describes her home as the place she feels most rooted. “It’s a refuge, a place to be with family,” she says. “Creating that framework where you can deal with everything that life throws at you is very important.”

We sit on a leather sofa below a sash window, fanned by a gentle breeze. Levete, dressed casually in a white shirt and jeans, wedges herself into a corner of the couch, tucking her bare feet beneath her, with me on the other. I immediately feel at home. But then this is an architect known for creating spaces you want to spend time in.

Although enormously well recognised among her own peer group, Levete and AL_A – the practice she established in 2009 alongside co-directors Ho-Yin Ng, Alice Dietsch and Maximiliano Arrocet – are most known for their work on the contemporary wing of London’s V&A’s Exhibition Road Quarter (2017), which includes the Sackler courtyard, whose design incorporates 11,000 handmade porcelain tiles. Or for the sweeping futuristic vision of Lisbon’s Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, better known as the MAAT, a building so spectacular that it attracted more than 80,000 visitors on its opening day (some 14 per cent of the city’s population). The building has been credited with helping to regenerate the waterfront area to the west of the metropolis, a typical Levete project that sets the mind racing.

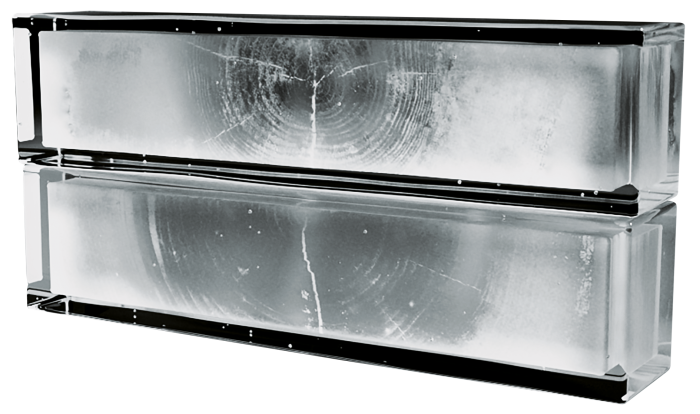

AL_A’s current projects include the radical £42m transformation of Scotland’s Paisley Museum, due to open in 2022, which will add a red glazed entrance hall to the neoclassical building. But most exciting are the projects that will take the business into the future. The first is research into a new material it’s calling “transparent wood” – a collaboration with Sonia Antoranz Contera, professor of biological physics at Oxford University, taking biophilic design into the space age.

“We are exploring how we can use nature to grow the materials of the future and to imagine how innovative materials can help us live better together with nature,” Levete says of their scientific explorations, which have involved extracting the lignin from wood, manipulating the cellulose structure and infusing bio resins to create a new material that is totally translucent. It is, she claims, stronger than steel and a better insulator than glass.

Transparent wood is not a material that is going into commercial use soon. But it’s a project that for Levete is typically ambitious. “As architects we need to dream,” she says. “We get a huge thrill working on projects where we don’t know where they are going, but then we make a move that we know is going to change the way people use a building or the way they see themselves.”

There can be no bigger dream right now, however, than Levete’s other current project: creating a prototype nuclear-fusion facility for the Canadian clean-energy firm General Fusion. Until recently, Levete’s commission had been kept top-secret, but she has become near-evangelical about the technology that claims to create an almost limitless energy source with no greenhouse emissions, pollution or nuclear waste. Harnessing “the process that powers the sun and stars”, she says, will “provide clean, cheap energy for everyone, forever”.

Levete’s involvement with General Fusion came about quite serendipitously. She met one of the scientists in charge of the project at a conference in Kuala Lumpur in 2017. “He had given this unbelievably inspiring talk and I came away believing that they would solve the world’s energy problems in 10 years’ time,” she explains.

So enthused was Levete she invited the scientist to speak to her team back in London. He brought a slideshow presentation with him, and the final image was a render of the proposed plant. “It was a shed. I just couldn’t hold back,” she recalls. “So I told him that as a thank you I would put a small team onto it to show him what the building could be. We did, and his team loved it.”

The project finally took off at the end of last year. “It is about the messaging of a building whose technology is so powerful it is going to change the world forever,” Levete says. “Someone arriving there needs to feel that sense of optimism and drama, and to do this we are revealing General Fusion’s ‘new sun’ both inside and outside of the building, making the process of fusion transparent. We are also bringing nature into the building to express the positive relationship of its technology with nature and sustainability – and to take away any fear.”

As with all her projects, Levete firmly believes in the power of architecture to communicate – on every level. “Architecture touches on so many different aspects of what it is to be human. It’s culture and aesthetics obviously, but it’s also politics, economics, urban planning and history,” she says. “It’s helping us find our place in the world with a future that is very uncertain. It is so important not to lose confidence in what that future could be.”

As it has for many, the past year has made Levete take stock. “I have felt a much greater sense of personal and collective responsibility to be more generous with our thinking, our money and our time – and to try to use our skills to address some of the big issues of the moment,” she says. “Housing, and affordable housing, is definitely one of those. It’s something that we have never really done but we have initiated our own research project. It’s very early days but we hope to use it as a calling card. We want to be entrepreneurial.”

This entrepreneurial spirit has long been part of Levete’s professional arsenal, and it is arguably one of her greatest strengths. She rose to prominence at the groundbreaking practice Future Systems, which she co-founded with the late avant-garde architect Jan Kaplický (her former husband), a visionary whose ideas pushed the limits – often well past possibility. She is credited with being the one who got things built. Together they created sinuous, organic buildings subverting the polite urban skyline: from the UFO-like Media Centre at London’s Lord’s cricket ground (the design won the RIBA Stirling Prize in 1999) to the shimmering globule that is Birmingham’s Selfridges building (2003) – its skin of thousands of aluminium discs likened by the architects to “the sequins of a Paco Rabanne dress”.

Given Levete’s track record in reshaping the urban landscape, it is interesting to hear what she has to say about London’s rapidly changing skyline. She is, after all, a local who has spent most of her life – save for a short spell in New York in her 20s – living at the heart of the action. She sees the current crisis as traumatic but also a catalyst for change – particularly when it comes to the one-size-fits-all approach of traditional institutions.

“What is the future of the big corporate spaces in Canary Wharf? I’ve never wanted to work in a space like that and have never designed a space like that,” she says. “A lot of these issues have been bubbling up for a while, even before the pandemic; they’ve just been accelerated and have intensified.” Levete predicts that future offices will house more diverse, engaging spaces leading onto a terrace or garden where people can be more sociable.

“The days of the faceless, monolithic office block are over. We need to stop building like this,” she says. “We are currently designing a development in Brussels that has interlocking spaces of different characters and volumes, with great access to the outdoors, opening windows and fabulous daylight – simple things that will improve the quality of life for everyone who works there.”

She embraces London the melting pot, both as a resident and an architect. “There has never really been a grand-master architectural plan for London, and in a way that is its power,” she says. “Take Paris, a city that is exquisitely beautiful, but the Haussmann plan – it can’t be changed, it can’t adapt. In fact, the whole Haussmann concept was about controlling people, and you kind of sense that. London is really free-formed and random. It’s diverse, it’s irreverent, it’s a reflection of us.”

Paris, of course, still holds many charms for the architect. Most notably, it is the home of the Centre Pompidou. “For me, it is one of the most important buildings of the 20th century because it democratised the notion of a museum. It was a completely radical move,” she says. “It’s maybe not the most beautiful building, but conceptually it shifted everything. I love buildings that make that shift.”

Richard Rogers, who conceived the building with Renzo Piano, is someone she considers as a mentor. He gave her one of her first jobs in the business. “I learnt so much, especially from Richard, not just as an architect but as a humanist, as an intellectual, as a family man, as someone who was able to gather amazing people around him, who inspired great loyalty and admiration, and who kind of created a family within the office,” she recalls.

She has fostered that same culture at her own practice and works closely with her three directors – who each bring an essential ingredient to the mix. “If one of the team has reservations about something, you have got to be courageous enough to pull back and ask questions. For me that is what collaboration means,” she says. “Architecture is not a linear process – you get diverted, and those diversions can be really positive. That’s what I have learnt about the power of resistance and pushing against boundaries – you can use that as a positive force.”

Levete has used the power of resistance throughout her career, famously turning down an offer to bid for Rupert Murdoch’s News International’s headquarters because she found the brief uninspiring. “Doing the right thing,” she explains, is at the core of her practice. “The right thing isn’t always the easiest thing – it won’t always win you the competitions or make you the nice money,” she says. “But you cannot hide behind a brief or a budget. You have to find a way of either making it work or changing it – or, if you have to, walking away from it.”

Comments