The AI doctor will see you now

Simply sign up to the Artificial intelligence myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

If artificial intelligence in healthcare brings to mind visions of robot surgeons, BioIntellisense’s stick-on sensor is bound to be a disappointment. Just 3 inches wide by 1 inch tall, this plastic and metal double hexagon was cleared last month by the US Food and Drug Administration for remote monitoring of vital signs with medical-grade accuracy.

Doctors at UCHealth, which runs 12 Colorado hospitals, say the device will let them send patients home earlier while still monitoring their respiratory rate, resting heart rate, skin temperature and even body position. The data can then be fed into computers that use machine learning to spot people who might need more attention, allowing early intervention and avoiding emergency hospital visits.

UCHealth has already used computer surveillance to fight sepsis, a potentially fatal complication from infection, on its wards. In its first six months, that tracking system reduced the time from recognition of sepsis to treatment by two hours and cut mortality by 30 per cent.

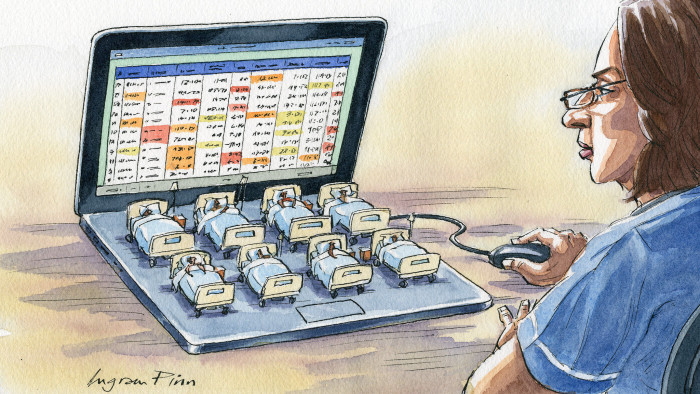

Such uses will also save money and staff time, says Richard Zane, UCHealth’s chief innovation officer. “Now, instead of one nurse monitoring eight people on a ward, she can monitor 8,000 people at home.”

At a time when insurers and public and private healthcare systems alike are struggling to contain costs, the attraction of artificial intelligence is strong. Some 367 healthcare AI start-ups received $4bn in funding last year, according to CB Insights. Investors are plunging into everything from sophisticated scheduling programmes that maximise the use of operating rooms to prediction systems that read mammograms or help gastroenterologists decide in real time whether to remove a polyp during a colonoscopy. The consultancy Accenture predicts that machine learning will create $150bn in annual healthcare savings in the US alone by 2026.

Many individual physicians have long been sceptical that machines can replace the personal touch. But attitudes are shifting. An American Medical Association survey last year found that 36 per cent of doctors believe digital health tools — particularly telemedicine and remote monitoring — definitely boost their ability to care for patients, up from 31 per cent in 2016.

In some ways, healthcare is now at the point where computer-driven financial trading was in the early 2000s. Back in 2005, computer-driven hedge funds, which use algorithms to follow market trends, managed less than $50bn in assets. By 2014, that had ballooned to $270bn, according to HFR data. Traders lost their jobs all over Wall Street and the City of London as strategies that relied on computers to spot opportunities and place rapid-fire trades — including high-frequency trading — exploded. By 2009, HFT accounted for 60 per cent of daily US equity trading, and it remains above half.

Experts in healthcare technology argue that the use of AI and machine learning will move much more slowly because of the need to secure regulatory approval and the dire consequences of getting decisions wrong.

When trading computers make mistakes — or contribute to panic — the trades can be reversed. Indeed, that’s what happened in the 2010 flash crash, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 9 per cent in minutes and bounced back up again. Wrong calls on healthcare are a very different matter, and many medical decisions involve choosing between imperfect options.

In some ways, the challenges ahead for AI in medicine are more like those faced by Uber, Waymo and the other designers of driverless cars. Machines are great at monitoring and handling straightforward situations — like driving down an uncrowded highway. But city streets and traffic jams are completely different. And designing the algorithms is only the first step. Winning public trust will be far harder, especially after the 2018 crash in which an Uber vehicle killed a pedestrian while its back-up safety driver was streaming a television show on her phone.

When it comes to medicine, most AI experts say that we are decades away from eliminating the need for doctors and nurses entirely. Success will come more quickly for applications that build in the human touch. These use AI to identify the most complicated situations and pass them on to doctors and nurses who are ready to handle them.

“Our strategy is to enable the frontal cortex of doctors rather than lobotomising them,” says Bill Evans, managing director of Rock Health venture fund.

The fund was a seed investor in Virta Health, which uses constant monitoring and AI to track and treat patients with type 2 diabetes. The computer alerts (human) health coaches and doctors when the data suggest patients need a nudge or a dosage change. An early clinical study found that more than 60 per cent of patients reversed their symptoms. The company is so confident that customers, including Blue Shield of California and US Foods, only pay if the aggregate patient results hit performance targets.

If pay for results spreads, the outcome could be even more revolutionary — and possibly frightening — than a robot surgeon.

Letters in response to this column:

Quick wins for AI in non-clinical healthcare / From Bryn Sage, Harrogate, N Yorks, UK

Help the public learn to trust AI with their health / From Vivian Bush, Beverley, E Yorks, UK

Comments