Francis Fukuyama: Putin’s war on the liberal order

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The horrific Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24 has been seen as a critical turning point in world history. Many have said that it definitively marks the end of the post-cold war era, a rollback of the “Europe whole and free” that we thought emerged after 1991, or indeed, the end of The End of History.

Ivan Krastev, an astute observer of events east of the Elbe, has said recently in The New York Times that “We are all living in Vladimir Putin’s world now”, a world in which sheer force tramples over rule of law and democratic rights.

There is no question that the Russian assault has implications that reach way beyond the borders of Ukraine. Putin has made it clear that he wants to reassemble as much of the former Soviet Union as possible, incorporating Ukraine into Russia and creating a sphere of influence that extends through all of the eastern European states that joined Nato from the 1990s onwards.

Though it is still too early to know how this war will evolve, it is already clear that Putin will not be able to achieve his maximal aims. He expected a quick and easy victory, and that Ukrainians would treat him as a liberator. He has instead stirred up an angry hornet’s nest, with Ukrainians of all stripes showing an unprecedented degree of tenacity and national unity. Even if Putin takes Kyiv and deposes President Volodymyr Zelensky, he cannot in the long run subdue a furious nation of more than 40mn with military force. And he will be facing a democratic world and Nato alliance unified and mobilised as never before, which has imposed costly sanctions on Russia’s economy.

At the same time, the current crisis has demonstrated that we cannot take the existing liberal world order for granted. It is something for which we must constantly struggle, and which will disappear the moment we lower our guard.

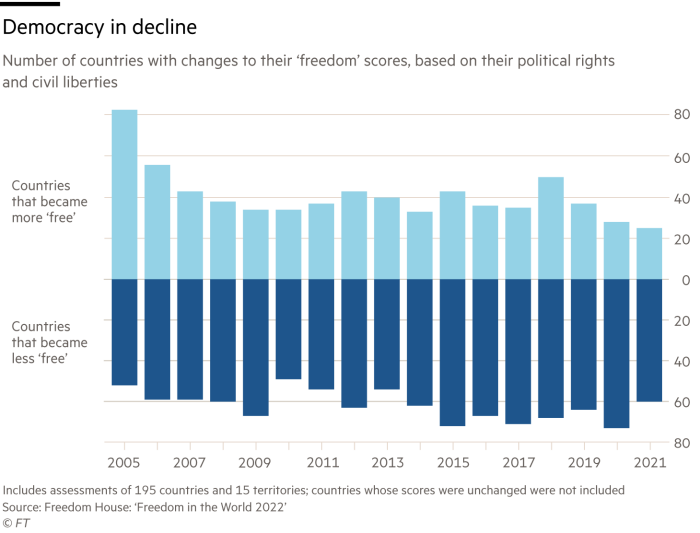

The problems facing today’s liberal societies did not start and do not end with Putin, and we will face very serious challenges even if he is stymied in Ukraine. Liberalism has been under attack for some time now, from both the right and the left. Freedom House in its “Freedom in the World” survey for 2022 notes that global freedom has fallen in the aggregate now for 16 years in a row. It has declined not just because of the rise of authoritarian powers such as Russia and China, but also because of the turn towards populism, illiberalism and nationalism within longstanding liberal democracies such as the US and India.

What is liberalism?

Liberalism is a doctrine, first enunciated in the 17th century, that seeks to control violence by lowering the sights of politics. It recognises that people will not agree on the most important things — such as which religion to follow — but that they need to tolerate fellow citizens with views different from their own.

It does this by respecting the equal rights and dignity of individuals, through a rule of law and constitutional government that checks and balances the powers of modern states. Among those rights are the rights to own property and to transact freely, which is why classical liberalism was strongly associated with high levels of economic growth and prosperity in the modern world. In addition, classical liberalism was typically associated with modern natural science, and the view that science could help us to understand and manipulate the external world to our own benefit.

Many of those foundations are now under attack. Populist conservatives intensely resent the open and diverse culture that thrives in liberal societies, and they long for a time when everyone professed the same religion and shared the same ethnicity. The liberal India of Gandhi and Nehru is being turned into an intolerant Hindu state by Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister; meanwhile in the US, white nationalism is openly celebrated within parts of the Republican party. Populists chafe at the restrictions imposed by law and constitutions: Donald Trump refused to accept the verdict of the 2020 election, and a violent mob tried to overturn it directly by storming the Capitol. Republicans, rather than condemning this power grab, have largely lined up behind Trump’s big lie.

The liberal values of tolerance and free speech have also been challenged from the left. Many progressives feel that liberal politics, with its debate and consensus-building, is too slow and has grievously failed to address the economic and racial inequalities that have emerged as a result of globalisation. Many progressives have shown themselves willing to limit free speech and due process in the name of social justice.

Both the anti-liberal right and left join hands in their distrust of science and expertise. On the left, a line of thought stretches from 20th-century structuralism through postmodernism to contemporary critical theory that questions the authority of science. The French thinker Michel Foucault argued that shadowy elites used the language of science to mask domination of marginalised groups such as gay people, the mentally ill or the incarcerated. This same distrust of the objectivity of science has now wandered over to the far right, where conservative identity increasingly revolves around scepticism towards vaccines, public health authorities and expertise more generally.

Meanwhile, technology was helping to undercut the authority of science. The internet was initially celebrated for its ability to bypass hierarchical gatekeepers such as governments, publishers and traditional media. But this new world turned out to have a big downside, as malevolent actors from Russia to QAnon conspiracists used this new freedom to spread disinformation and hate speech. These trends were abetted, in turn, by the self-interest of the big internet platforms that thrived not on reliable information but on virality.

How liberalism evolved into something illiberal

How did we get to this point? In the half-century following the second world war, there was broad and growing consensus around both liberalism and a liberal world order. Economic growth took off and poverty declined as countries availed themselves of an open global economy. This included China, whose modern re-emergence was made possible by its willingness to play by liberal rules internally and externally.

But classical liberalism was reinterpreted over the years, and evolved into tendencies that in the end proved self-undermining. On the right, the economic liberalism of the early postwar years morphed during the 1980s and 1990s into what is sometimes labelled “neoliberalism”. Liberals understand the importance of free markets — but under the influence of economists such as Milton Friedman and the “Chicago School”, the market was worshipped and the state increasingly demonised as the enemy of economic growth and individual freedom. Advanced democracies under the spell of neoliberal ideas began trimming back welfare states and regulation, and advised developing countries to do the same under the “Washington Consensus”. Cuts to social spending and state sectors removed the buffers that protected individuals from market vagaries, leading to large increases in inequality over the past two generations.

While some of this retrenchment was justified, it was carried to extremes and led, for example, to deregulation of US financial markets in the 1980s and 1990s that destabilised them and brought on financial crises such as the subprime meltdown in 2008. Worship of efficiency led to the outsourcing of jobs and the destruction of working-class communities in rich countries, which laid the grounds for the rise of populism in the 2010s.

The right cherished economic freedom and pushed it to unsustainable extremes. The left, by contrast, focused on individual choice and autonomy, even when this came at the expense of social norms and human community. This view undermined the authority of many traditional cultures and religious institutions. At the same time, critical theorists began to argue that liberalism itself was an ideology that masked the self-interest of its proponents, whether the latter were men, Europeans, white people or heterosexuals.

On both the right and the left, foundational liberal ideas were pushed to extremes that then eroded the perceived value of liberalism itself. Economic freedom evolved into an anti-state ideology, and personal autonomy evolved into a “woke” progressive worldview that celebrated diversity over a shared culture. These shifts then produced their own backlash, where the left blamed growing inequality on capitalism itself, and the right saw liberalism as an attack on all traditional values.

The global context

Liberalism is valued the most when people experience life in an illiberal world. The doctrine itself arose in Europe after the 150 years of unremitting religious warfare that followed the Protestant Reformation. It was reborn in the wake of Europe’s destructive nationalistic wars of the early 20th century. A liberal order was institutionalised in the form of the European Union, and the broader global order of open trade and investment created by US power. It received a big shot in the arm between 1989 and 1991 when communism collapsed and the peoples living under it were freed to shape their own futures.

However, more than a generation has passed now since the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the virtues of living in a liberal world have been taken for granted by many. The memory of destructive wars and totalitarian dictatorship has faded, especially for younger people in Europe and North America. In this new world, the EU, which succeeded spectacularly in preventing European war, was now seen by many on the right as tyrannical, while conservatives argued that government mandates to wear masks and be vaccinated against Covid-19 were comparable to Hitler’s treatment of the Jews. This is something that could only happen in a secure and complacent society that had no experience of real dictatorship.

Moreover, liberalism can be uninspiring to many people. A doctrine that deliberately lowers the sights of politics and enjoins tolerance of diverse views often fails to satisfy those who want strong community based on shared religious views, common ethnicity or thick cultural traditions.

Into this void have stepped illiberal authoritarian regimes. Those of Russia, China, Syria, Venezuela, Iran and Nicaragua have little in common other than the fact that they dislike liberal democracy and want to maintain their own authoritarian power. They have created a network of mutual support that has allowed, for example, the despicable regime of Nicolás Maduro in Caracas to survive despite having driven more than a fifth of Venezuela’s population into exile.

At the centre of this network is Putin’s Russia, which has provided weapons, advisers, military and intelligence support to virtually any regime, no matter how awful to its own people, that opposes the US or the EU. This network extends into the heart of liberal democracies themselves. Rightwing populists express admiration for Putin, beginning with former US president Trump, who called Putin a “genius” and “very savvy” after his invasion of Ukraine. Populists including Marine Le Pen and Eric Zemmour in France, Italy’s Matteo Salvini, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, leaders of the AfD in Germany and Hungary’s Viktor Orban have all shown sympathy for Putin, a “strong” leader who acts decisively to defend traditional values without regard for petty things such as laws and constitutions. The liberal world has brought about huge increases in gender equality and tolerance for gay and lesbian people over the past two generations, which has provoked some on the right to worship masculine strength and aggression as virtues in themselves.

The spirit of 1989 isn’t dead

This is why the current war in Ukraine matters to all of us. The unprovoked Russian aggression and shelling of the peaceful Ukrainian cities Kyiv and Kharkiv has reminded people in the most vivid way possible what the consequences of illiberal dictatorship are.

Putin’s Russia is seen clearly now not as a state with legitimate grievances about Nato expansion but as a resentful, revanchist country intent on reversing the entire post-1991 European order. Or rather, it is a country with a single leader obsessed with what he believes to be a historical injustice that he will try to correct, no matter the cost to his own people.

The heroism of Ukrainians rallying around their country and fighting desperately against a much larger enemy has inspired people around the world. President Zelensky has come to be seen as a model leader, courageous under not metaphorical but real fire, and a source of unity for a previously fractured nation. Ukraine’s solitary stand has in turn provoked a remarkable upwelling of international support. Cities around the world have decked themselves in blue-and-gold Ukrainian flags, and have promised material support.

Contrary to Putin’s plans, Nato has emerged stronger than ever, with Finland and Sweden now thinking of joining. The most remarkable change has occurred in Germany, which previously had been Russia’s biggest friend in Europe. By announcing a doubling of the German defence budget and willingness to supply arms to Ukraine, Chancellor Olaf Scholz has reversed decades of German foreign policy and thrown his country wholeheartedly into the struggle against Putin’s imperialism.

Although it is hard to see how Putin achieves his larger objectives of a greater Russia, we are still facing a long and dispiriting road ahead. Putin has yet to bring to bear all of the military force Russia has at its disposal. Ukraine’s defenders are exhausted and running out of food and ammunition. There will be a race between Russia resupplying its own forces, and Nato seeking to bolster Ukrainian resistance. As Russia doubles down, Ukrainian cities are suffering indiscriminate shelling, and tragically are coming to resemble places, such as Grozny in Chechnya, that suffered similar Russian bombardment in the 1990s. There is also a danger of escalation of the fighting to direct clashes between Nato and Russia as calls mount for a “no-fly” zone. But it is the Ukrainians who will bear the cost of Putin’s aggression, and they who will be fighting on behalf of all of us.

The travails of liberalism will not end even if Putin loses. China will be waiting in the wings, as well as Iran, Venezuela, Cuba and the populists in western countries. But the world will have learnt what the value of a liberal world order is, and that it will not survive unless people struggle for it and show each other mutual support. The Ukrainians, more than any other people, have shown what true bravery is, and that the spirit of 1989 remains alive in their corner of the world. For the rest of us, it has been slumbering and is being reawakened.

Francis Fukuyama is a senior fellow at Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law, and author of the forthcoming ‘Liberalism and Its Discontents’ (Profile Books)

Data visualisation by Liz Faunce

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

Letter in response to this article:

Consequences of invasion will affect us for years / From Carol Symons, London NW8, UK

Comments