The EU-China deal that gives Beijing too little to lose

Simply sign up to the Global Economy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

FT premium subscribers can click here to receive Trade Secrets by email.

Hello from Brussels. Following the EU’s investment deal with China — of which more below — it’s the US’s turn to provoke a cry of “whose side are you on?” from its allies and trading partners.

Joe Biden is set to sign a “buy American” order restricting some public procurement to US companies. (We’ll be looking out for a passive-aggressive tweet from the European Commission about working with the Biden administration on procurement alliances against China.) How far Biden’s plan represents economically and diplomatically disruptive protectionism depends on the detail: which sectors, which exemptions, what loopholes for foreign companies arising from US commitments in deals like the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and the WTO government procurement agreement (GPA).

Speaking of which, the Trump administration (remember them?) in November started the process of pulling the US out of part of the GPA. Sounds dramatic, but after apparently having considered a broader withdrawal, in the end it was restricted to just some spending to do with essential medicines. Today’s main piece looks at the aforementioned EU-China deal, now that we have a bit more information on it, while Tit for Tat asks White & Case’s Henning Berger what to expect from the forthcoming memorandum of understanding between the UK and the EU on financial services.

Don’t forget to click here if you’d like to receive Trade Secrets every Monday to Thursday. And we want to hear from you. Send any thoughts to trade.secrets@ft.com or email me at alan.beattie@ft.com

The skinny agreement with chunky risks for Brussels

On Friday, the EU released draft texts from the somewhat controversial Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) with China that was sealed “at a political level”, as the saying goes, at high speed in the dying days of December. If you think it’s weird that the EU proudly announces a deal before the detail is agreed and known by member states, you’re probably new around here.

We still don’t know the full substance, since the detailed “schedules” showing market access by sector won’t be out for a few weeks. We heard a mischievous suggestion that getting the schedules out by February 11 would completely satisfy the two sides’ promise to have the deal done before the new year, assuming they were working to the traditional Chinese calendar (February 12) rather than the Gregorian (January 1). But we digress.

The most controversial stuff, which will encounter serious turbulence in the uncertain waters of European Parliament ratification, is on labour standards and human rights. We’ll give those (and the wider issue of labour and trade) a detailed examination in a week or two, and today focus on economic substance, dispute settlement and the political balance of power.

First, as University College London’s Lauge Poulsen, one of our favourite gurus in this area, points out, this investment agreement doesn’t really contain investor protection. It certainly doesn’t create an investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism for companies to sue governments for unfair treatment. In theory the EU and China will separately negotiate an ISDS deal over the next few years, but don’t hold your breath. Beijing doesn’t much like the EU’s transparent version of ISDS, and few European companies are clamouring for more opportunities to enrage Beijing by suing it for discrimination or expropriation.

Instead, the CAI largely locks in liberalisation in foreign direct investment that China has already voluntarily undertaken in a number of sectors — which, this being China, will still often be subject to government discretion. For example, it allows foreign investors to set up electric vehicle manufacturing plants without requiring a local partner, but this is apparently subject to the government’s judgment about whether spare capacity already exists.

There might be more substance in side deals, or at least informal understandings, struck directly between China and EU member state governments, with most attention focused on Germany and France. No one knows for sure. But if we had to bet we’d look at companies from member states, not just Germany, getting telecoms operator licences in China in proportion to their government’s willingness to admit Huawei to their 5G systems at home. We’d also expect an Airbus plant or two at a rather more sophisticated technological level than the final assembly factory it currently has in Tianjin, plus other European companies investing in China in strategic emerging industries such as advanced materials and renewable energy in return for a share of the Chinese domestic market.

China doesn’t get much market access in return, since the EU is already pretty open to foreign investment. That sounds like a problem for China with this deal: it’s also a problem for the EU. Brussels will struggle to effect change in Beijing’s behaviour without being able to punish it by removing market access, either by using the agreement’s dispute settlement system or threatening to tear up the whole thing. When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose, as a noted trade analyst once put it. An EU official told journalists last week that the EU might for example, withhold licences from Chinese companies to establish services or to build manufacturing plants, but accepted it would be much harder to retaliate than under a comprehensive trade agreement where Brussels could much more easily raise tariffs.

De facto enforceability is a real challenge in this deal. On paper, the agreement isn’t meaningless. There are some potentially useful provisions on forced technology transfer, transparency of subsidies and the operations of state-owned enterprises which could at the margin increase predictability for foreign companies operating in China. But if these become too burdensome to Beijing, given its minimal economic gains, does China ultimately care if it walks away? Does it really have as much invested politically as the EU does? Certainly, unlike Emmanuel Macron or Germany’s governing CDU, Xi Jinping doesn’t have any tricky regional or national elections coming up this year where the deal might become an issue.

The political judgment around the agreement is much harder than the economic, not least since it depends whether it spurs or deters transatlantic co-operation. For the moment we’re sticking with our initial take that the EU — and specifically the deal’s champions in Berlin and Paris — have more credibility on the line than has China, and that the risk to the EU’s credibility seems too high for the deal to be worth it. We’re open to being persuaded otherwise, but we’re going to take quite a lot of convincing.

Charted waters

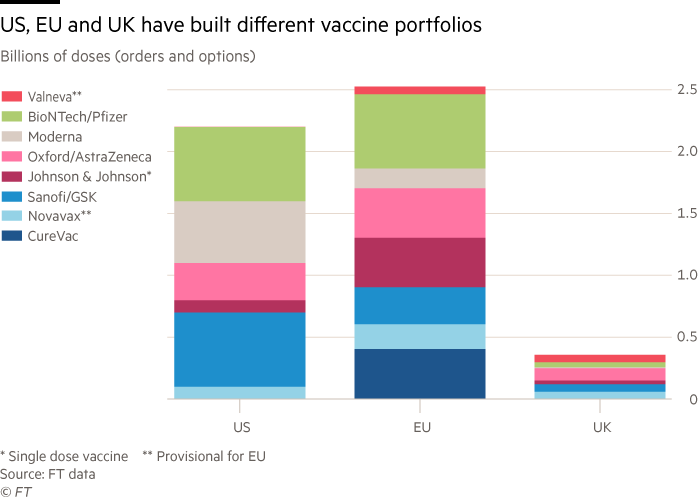

The EU has hit another stumbling block in its plans to rollout mass vaccination programmes across the region. On Friday it emerged that AstraZeneca had warned EU countries to expect significant shortfalls to early deliveries of its vaccine, which the region’s medical authorities could approve as soon as this week. The chart below sheds some light on what is, and isn’t, the problem with the EU’s vaccination drive.

The EU has, like the US and the UK, ordered more than enough vaccine doses to meet the needs of its population. The trouble is both the US and UK were quicker to order the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine and quicker to approve the usage of this and the other candidates, such as the AstraZeneca jab, which the UK approved in December. That has meant the EU is further down the pecking order to receive its doses.

Tit for tat

We asked Henning Berger, partner at White & Case, three questions about how Brexit will alter Europe’s financial services industry.

1. Financial services received far less attention in the Brexit deal than trade. That has created some teething problems for the City of London. But in the longer term are you more optimistic?

It is true that the City of London suffered significant losses in the area of financial services in the run up and few weeks after Brexit, with the full impact still evolving. However, I remain optimistic as to the longer term outlook for the City. For one, many institutions have reorganised their European operations in anticipation of a hard Brexit well in advance of 31 December 2020, and therefore reduced their dependency on the Single Market. Secondly, there are good reasons for the EU to grant equivalence to the UK, even if the UK should decide to deviate from the EU rules over time. Thirdly, it is a significant advantage that the UK can remove some of the red tape binding financial services in the EU, without falling outside internationally accepted standards, making the City it a more attractive international hub in the long term.

2. The UK and EU have pledged to work on a memorandum of understanding on financial services. What do you expect this to yield?

The memorandum of understanding expected for March 2021 is supposed to establish the framework for a structured regulatory co-operation between the EU and the UK. The parties aim at a durable and stable relationship, with the intention to preserve financial stability, market integrity and the protection of investors and consumers. The memorandum shall also provide for arrangements on how both sides deal with equivalence determinations in the future. This is of great importance to allow market access in those areas of financial services, where third country equivalence regimes exist, and the EU currently allows market access to firms from the US for example. I expect the parties to agree on transparent criteria and reliable processes concerning the adoption, suspension and withdrawal of equivalence decisions, which is key to safeguard the interests of the market participants.

3. The focus has been on how eurozone financial centres could benefit from London's demise. Which cities in the region can you see thriving? And could some business disappear outside of Europe to financial centres such as New York?

So far, it seems that especially Paris, Frankfurt and Amsterdam have benefited from the relocation of operations and staff from London. Furthermore, institutions from countries such as the US and Asia wanting to access the EU market, now rather choose one of those cities than London. This process is likely to continue over the next years with all cities benefiting. As to financial centres outside of Europe it seems, at least from a regulatory perspective, rather improbable that business will move, as there is no apparent tendency to liberalise trading between the EU and third countries. However, assuming that third-country market access between the UK and the EU will in future not be significantly better than between the US and the UK, competition could move EU related business from the City to New York over time.

Don’t miss

James Politi has more on US president Joe Biden’s plans to tighten “buy American” provisions as part of a push to boost domestic manufacturing, in a move that risks straining relations with key US allies.

Read moreSaudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund is seeking to use its financial muscle to lure international health and technology companies to set up operations in the kingdom.

Read moreMore on the problems North Korea faces in vaccinating its population. Kim Jong Un faces a Covid dilemma of isolation or vaccination, write Ed White and Alice Woodhouse.

Read more

Tokyo talk

The best trade stories from Nikkei Asia

Taiwan’s Economic Ministry is asking domestic chip manufacturers to help “like-minded” economies such as the US, Japan and Europe to alleviate the global shortage of automotive-related chips.

Read moreJapan’s panned “China exit” subsidy is helping niche suppliers to semiconductor industry giants expand their domestic supply chains as the global chip shortage heats up.

Read more

Comments