Life lines: textile works by the late Feliciano Centurión

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

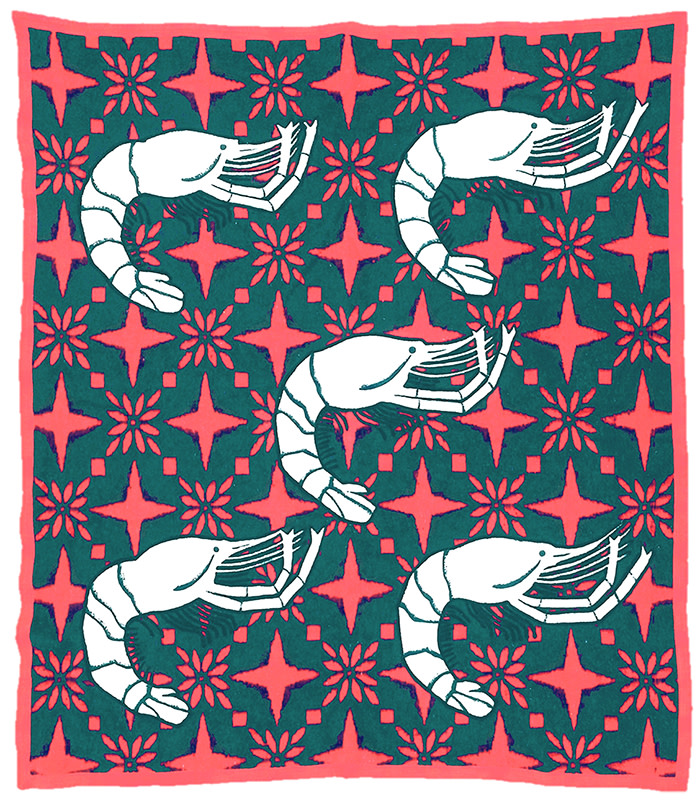

Now in its fifth year, Art Basel Miami Beach’s focused Survey section brings 20th-century artists into the present — and often proves a discovering delight. Among the treasures this year is Feliciano Centurión, a Paraguay-born artist who died in 1996, at just 34, from the complications of Aids. For this year’s fair, Buenos Aires gallery Walden brings a selection of seven of Centurión’s embroidery works from 1990 to 1993 that transform cheap, mass-market blankets into delicate pieces of confessional art (prices range from $30,000-$90,000).

It’s the first time the artist’s work has been shown in depth at a major-league art fair. Gallery founder and director Ricardo Ocampo says the decision to highlight Centurión was prompted by the artist’s inclusion in the coinciding 33rd Bienal de São Paulo (until December 9). There, he is one of 12 artists chosen by director and chief curator Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro for a solo showing, which includes his embroidered and crocheted works on blankets, pillows and other intimate household wares.

“Very few people know about him, but he is finally getting some recognition,” Pérez-Barreiro says, noting that the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas, is the only institution with any significant holdings of Centurión’s work. Madrid’s Reina Sofia Museum now also has work by Centurión, part of a donation from the collector Patricia Phelps de Cisneros.

The gallerist Cecilia Brunson, who represents the artist’s estate in close collaboration with his two sisters, says of Centurión’s relative invisibility that he was “really at the margins of everything”. Under the rightwing dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner, Centurión’s family was forced out of the rural Paraguayan town of San Ignacio Guazú into the tiny village of Alberdi, on the border with Argentina. Their father crossed to Formosa in Argentina every day to work. Feliciano was raised mostly by his mother and grandmother, and was a gay man in an ultra-conservative society. The artist’s move to Buenos Aires in the 1980s put him more at the cultural centre of things — he became part of the city’s irreverent and progressive Arte Light movement — but he was diagnosed with HIV in 1992, which kept him on the fringes of society.

His art was also niche. Trained as a painter, he started out making large erotic works. But, Brunson says, “painting was the official language of the dictatorship and of the resistance; he wanted to express himself in a different way.” Centurión and others in the Arte Light movement turned to irony, colour and kitsch to represent repression. “He was serious, but also poking fun at so-called good taste,” Pérez-Barreiro says.

Centurión’s handicraft recalls his female-dominated upbringing, a Paraguayan legacy since the 1864-70 War of the Triple Alliance, which devastated the country’s male population. After his HIV diagnosis, Centurión worked in increasingly small and intricate formats. He liked to embroider animals and mythical beings, in keeping with Paraguay’s Guaraní weaving traditions, and used his own text, too, often in reference to his ill-health.

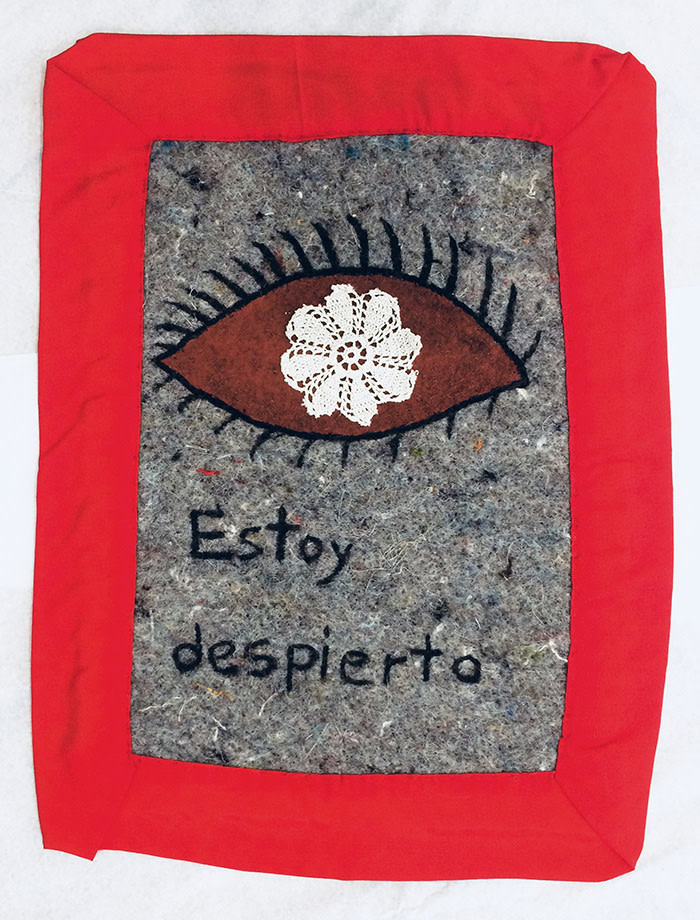

One of the works that Walden gallery brings to Miami this week features a large eye, its pupil embroidered as a staring, white flower, with the phrase underneath “Estoy despierto” (“I am awake”), in open awareness of his imminent death. Another work, not at the fair, reads “La muerte es parte intermitente de mis dias” (“Death is a recurring part of my life”).

Brunson will open Centurión’s first London show in January, titled I am awake. She finds that his work chimes with the body politics of today, not least under Brazil’s new rightwing and openly homophobic president Jair Bolsonaro. “Centurión had a desire for his voice not to be silenced by the ideologies around him,” she says. “It’s so timely to look at him now.”

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments