The Diary: Chris Cook

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Stately Nanjing is not as glamorous as Shanghai or as busy as Beijing but it tells the story of China’s development. New buildings are popping up along the main arteries to house the eastern city’s surging population – already 8m. City authorities are firmly in favour of becoming a megacity.

Most Chinese officials punctuate their sentences with the words “harmonious” and “dynamic”. In Nanjing, home to the mausoleums of the first Ming emperor and the first president of the Republic of China, the word “historic” is also regularly used. Yet construction has swamped the old city. Aside from a few ancient buildings and a medieval wall, the town gives little hint of its age. All is new; much gleams.

The result is that in poor light, of which the smoggy city has plenty, the centre of what was once the capital of China could pass for a prosperous eastern European town. The middle class is getting rich fast – as the car parks attest. This is not a city of wheezing jalopies. You take your life in your hands crossing highways but you are, at least, only at risk from the grandest marques.

…

I was in the city for a week as part of a delegation of European journalists, organised by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a think-tank. The trip was, among other things, intended to encourage discussion between western reporters and journalists in China. But our timing was sadly impeccable: we wandered into a local political scandal which left the oppression of socialism “with Chinese characteristics” as thick in the air as the soot.

Immediately before our arrival, Ji Jianye, the city’s mayor, became the latest high-profile defendant in Beijing’s purge of the “tigers and flies” – a national corruption crackdown that, one cannot help noticing, seems to hurt the leadership’s foes more than its friends. Then, during our visit, a newspaper made a front-page appeal for the release of Chen Yongzhou, a young journalist in distant Hunan who was arrested after reporting that Zoomlion, a manufacturing company, had engaged in some rather unsavoury business practices (allegations it strongly denies).

It was not entirely surprising, then, that our delegation was accompanied by some odd people with curious job descriptions – “academics” with no discernible expertise, “journalists” who seemed to lack any bylines. Their purpose was fairly clear. They were there to make sure that the Chinese journalists knew to evade and avoid questions about the mayor or free speech.

Still, we learnt enough. We were taken to a press conference with Yang Weize, Communist party secretary for Nanjing – the local boss. The meeting was held in a conference centre that would be perfect for powwows among Bond villains, nestled by a lake in secluded parkland outside the heart of the city; the meeting itself was in a high-ceilinged throne room. We were each permitted one question.

I asked how one could show Ji’s prosecution was not politically motivated; rumour-mongers noted his links to former president Jiang Zemin. Yang acknowledged this had happened during the Cultural Revolution, but stressed China was now “on the right track of the rule of law”. This would have been more convincing if he had not already likened Ji, who is yet to face any sort of trial, to “a malignant tumour”.

Meanwhile, Chen, the imprisoned journalist, was not released. In fact, as a headline in the loyal Shanghai Daily reported, his newspaper apologised after Chen confessed to “fabricating articles”. The 27-year-old appeared on television – shaven-headed and hands in cuffs – to make a confession. He said a middleman – as yet unnamed – had bribed him to run the stories, paying him $80,000 for bringing down the stock price.

Some of the Chinese journalists immediately smelt a rat. Of course, he is being forced to say this. Unverifiable samizdat accounts of the arrest allege strong links between Zoomlion and the local forces of law and order. But other local hacks shrugged that it was a shame this young man had proved so corruptible. He confessed – what more do you need to know?

I had never heard of Zoomlion nor been to Hunan. But many journalists in China take extreme personal risks to break stories and take great care to make sure they have their facts straight. Before this week, Chen was considered one of them.

…

The trip also took in some traditional local culture – notably a taster of Chinese opera (surprisingly unterrible) and massage by blind masseurs (murderously painful). We were taken round the universities that are shooting up across the city. Yang’s plan is that Nanjing should be Boston to Shanghai’s New York – a historic city and world-renowned higher education hub.

A former education correspondent, I’m used to having headteachers put on a bit of a show. I was, however, surprised by the East Beijing Road Primary School. We were treated to – in order of appearance – a mass kung fu demonstration, a fan dance, a group of cheerleading tots in skin-tight leotards with exposed midriffs, a short play, a choir and then a tour of the premises.

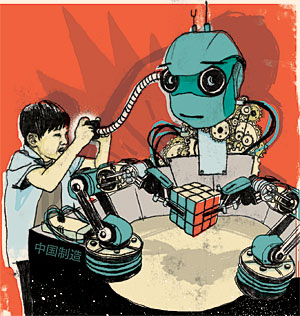

Still, it seems to work. I also witnessed a sight that would haunt the dreams of education ministers in the west. In a science classroom a giggly 10-year-old boy handed me a Rubik’s cube. Happily, it was already completed. I was not about to be humiliated by a child. He made a twisty hand gesture – ah, he wanted me to scramble it. I could do that.

After a few twists, I tried to hand him the cube. He shot me one of the looks of scorn that clever little boys reserve for stupid adults. More twisting, he gestured. So I kept going. Finally, I had done enough, at which point he put it into the robot he had built and programmed to solve it. The robot scanned the surface of the cube, started swivelling and – minutes later – voilà.

Are our own feckless, porky children doomed? If it is any consolation, the kid’s teacher was as alarmed as we were. And not all of China’s education is so high-tech. At the schools we visited, a song played twice a day advising children to rub their eyes and the bridge of their nose according to traditional routines. “It’s supposed to stop us getting shortsighted,” said one bespectacled teenager. “Do you think it works?” I asked. I got another of those “stupid adults” looks.

——————————————-

Chris Cook is the FT’s executive comment editor

Comments