Wirecard’s problem partners

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Agostin Antonio was mystified. A retired seaman living quietly with his extended family of 12 in a suburb of the northern Philippine city of Cabanatuan, he had no idea why a company called ConePay International had used his address.

But the name did ring a bell. Avoiding the laundry drying in the front porch and stepping over his grandchildren playing at the kitchen door, Mr Antonio disappeared back into his typical single-storey home, emerging a few moments later with a large white envelope.

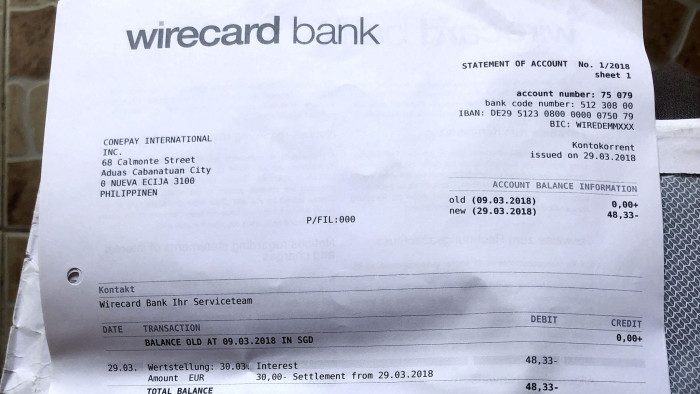

Addressed to ConePay, the letter had arrived in the mail about a year ago, a single missive from an entity called Wirecard Bank. It was a 10-page set of statements for empty German bank accounts held in a string of currencies — Australian, Canadian and Singaporean dollars and British pounds.

Mr Antonio didn’t know anything about Wirecard Bank either.

“This house was my mother’s. It’s been with the family for 50 years.” It was an unlikely location for an international electronic payments business.

ConePay is one of more than a dozen curious companies identified during an Financial Times investigation which, on paper at least, appear to have done substantial business with Wirecard, a digital payments group that ranks as an elite German blue-chip institution and one of the most successful fintech businesses in Europe.

Wirecard often encounters online businesses for which it does not wish to process payments due to network payment rules, because it lacks the appropriate licences or other potential risks. The clients are referred instead to so-called “third-party acquirers”, which share processing fees with the German group as commission.

Known internally as “referring”, it is by some distance Wirecard’s largest business line. The FT has been told by whistleblowers that at the start of 2018 it was expected to contribute half of the €2bn in worldwide sales Wirecard forecast for that year.

The company confirmed the magnitude of such business, which it said was declining. It said nearly half its transaction volumes originate from countries where it does not hold the necessary payments licences, so it partners with “more than 100 processors, acquirers, issuers and local service providers” which do. Wirecard said every multinational payments processor relies on such networks, and its accounting treatment of the resultant revenues and costs is consistent with international standards.

Processing payments for the murkier parts of online commerce is highly lucrative. However, Wirecard said less than 10 per cent of its volumes “relate to lottery, gambling, dating, adult entertainment and associated business models”, and strict compliance and governance rules apply.

The outsize revenue contribution of referring partnerships has not been a highlight of management commentary in recent years, as the company has explained its breakneck growth in terms of technological advances and Asia Pacific expansion.

Longstanding and large commercial debts owed to Wirecard by these secret partners, revealed today by the FT, raise questions about the robustness of the sales and profits attributed to them.

ConePay, incorporated at the house in Cabanatuan three hours’ drive north from the capital Manila, was the source of millions of euros in commission income accrued by Wirecard’s Singapore business in recent years — revenues that the FT has discovered often lacked the paperwork to justify them and that Wirecard’s accounts staff in the region failed to collect for more than three years.

Police from Singapore’s commercial affairs department are investigating whether senior Wirecard staff have been using fake companies and doctored contracts to boost revenues artificially over several years.

The probe follows a preliminary investigation last year by Singaporean law firm Rajah & Tann, which found evidence of suspected fraud, forgery and money laundering.

At the end of January, the FT published details of that R&T report. Following a fall in Wirecard’s share price, it claimed manipulation by short sellers. In response, prosecutors in Munich opened an investigation into market activity and BaFin, Germany’s financial regulator, slapped a unique ban on short sales of Wirecard stock, citing risks to the economy and market stability.

On Tuesday, Wirecard published its own summary of R&T’s summarised findings submitted to the company. It said a few Singapore employees may face “criminal liability”. It also said R&T “could not correlate certain payments made between business partners and Wirecard entities with agreements between them”. The company said it since had improved internal processes.

Wirecard also announced that an accounting review of transactions was undertaken by an independent consulting firm. It said “the independent review made no findings of round tripping or corruption”, and that no finding had a material impact on the company’s financial results. Round tripping is the process of making money transfers in and out of a company look like revenue derived from legitimate business.

Further investigations by the FT have identified a vivid mismatch between the supposed scale of the partner businesses to which Wirecard entities have ascribed substantial revenue, and the modest reality on the ground in countries such as the Philippines.

For instance, a predecessor of ConePay, Maxcone, gave as its address in 2015 what is currently an empty warehouse and office on a scruffy street in the southern Metro Manila city of Las Piñas, formerly occupied by a garage called Sam’s Autoworx and a bar called Hrai. When visited by FT reporters earlier this year, the local government office responsible for business permits knew of no payment company ever operating in its district.

The registered office of two other Wirecard partners, Centurion Online Payment International and PayEasy Solutions, is found in an office building by Manila Bay, in Metro Manila’s city of Pasay. While PayEasy logos are plastered over the office, the space doubles up as the headquarters of Froehlich Tours, a bus and coach rental business that operates across the country.

PayEasy and Froehlich Tours are owned by Christopher Bauer, a German former Wirecard Asia Pacific executive, and his wife Belinda Bauer, according to public filings. Centurion has made no filings since 2013. Both Bauers have represented Centurion in interactions with Wirecard.

Pinned to a wall of the office was a memo to staff signed by Mr Bauer, whose Facebook profile in 2016 described him as chief executive of Froehlich Tours. He told the FT he was just an investor, and that as a board member he “does not have much to do with the day-to-day operations” of the bus company. He also denied having a managerial role in PayEasy, which he said provides payments solutions for commuter services offered by the bus firm.

Wirecard describes itself as an integrated payments group which provides services such as pre-paid cards and a digital payments app. It also offers back-office support and refers business to scores of affiliated smaller companies offering payment services.

What links these specific Wirecard partners in and around Manila is that their names are on stacks of unpaid bills, some lingering for years, sitting in the books of Wirecard’s accounts processing department in Singapore.

Staff at Wirecard’s cash-strapped business in Singapore struggled to collect money they believed was due from ConePay and Centurion — or even produce paperwork required to justify the debts, according to whistleblowers.

ConePay, Centurion and PayEasy also featured in a list of “special items” seen by the FT, in a March 2017 snapshot of commercial debts owed to Wirecard by a dozen companies, for a total of €210m.

The situation adds another layer of intrigue to allegations made by whistleblowers that some Wirecard executives forged invoices and fabricated money flows as part of a widespread book-cooking operation.

Wirecard, which until recently was worth more than Deutsche Bank, has reported rapid growth for years as it expanded across Asia, claiming to reinvent the payments industry and presenting itself as the future in a world where cash is obsolete. Criticism of its accounting and business practices has been dismissed by management as market manipulation by hedge funds mounting so-called “short attacks”.

Behind the hype that portrays Wirecard as a tech company leading an e-money revolution, it has been unclear how much the company relies on third parties for its growth and profits. The existence of such external partners has long been disclosed, but not the size of the referring business.

The company’s practice of not drawing attention to some of its partnerships may reflect the fact that they offer payment services to unsavoury sectors.

Documents seen by the FT suggest that the internal explanation for the relationship with the Philippine businesses was that some customer payments were considered too sensitive for Wirecard to handle directly. As a result, they were instead referred to third-party payment providers, in return for commission.

“Maxcone (ConePay) and Centurion nature, their merchants are all porn and gambling company Wirecard cannot process so refer to them,” a senior member of Wirecard’s Singapore finance team told a colleague on February 12, 2018. “Better keep it a secret,” she added, in correspondence seen by the FT.

For instance, Centurion was expected to process payments for a collection of Japanese adult websites, according to information provided by whistleblowers. Wirecard paid €12m for these customer relationships in 2011, a side deal to its purchase of what became Wirecard Singapore.

Critics and supporters of the company alike acknowledge that its business model is opaque and financial disclosure limited. But figures seen by the FT may surprise investors and analysts: 2018 revenues attributed to “referring”, involving third parties such as ConePay and Centurion, were expected to be €931m, half of Wirecard’s forecast for worldwide sales.

The contribution is so large in part because the group has not just reported the commission income as sales. For the purpose of its accounts, Wirecard argues it is sufficiently involved in some transactions to treat the revenues and costs of several third parties as its own.

Back in 2015, Jan Marsalek, Wirecard’s chief operating officer, provided the Singapore office with invoices for payments that Centurion and Maxcone were due to make. Together worth about €700,000 in commission every three months, the sums meant the Philippines companies counted among the top six customers for Wirecard Singapore that year. A senior Asia-Pacific executive told a member of the finance team not to include them in an investor presentation, however: “We shouldn’t show ‘special’ customers such as Maxcone in there really,” he said.

Centurion and Maxcone — along with the other Philippine entity, PayEasy — also received “special” status on a spreadsheet sent to Stephan von Erffa, Wirecard’s deputy chief financial officer, in July 2017. The document listed €210m of commercial debts known as receivables owed to six Wirecard businesses in India, Germany, Ireland, Dubai, Singapore and Gibraltar.

The company said such figures “do not correctly reflect the Q1/2017 receivables positions in Wirecard’s financial statements”. It also said it presumes the FT’s information was “part of a package of largely false and misleading information”, which it claimed the FT had “repeatedly misquoted”.

While the numbers for Centurion and Maxcone (ConePay) were relatively small, PayEasy was listed as owing Wirecard in Germany €123m at the end of March that year.

It is unclear what made the debt “special”. A client of PayEasy referred to in Wirecard documents was Escalion, a Luxembourg payments business in the Docler group of companies behind Live Jasmin, a popular adult site.

Mr Bauer said to his knowledge “all paperwork between PayEasy and its partners as well as the company’s public records are in order and PayEasy has always honoured all of its payment obligations to third parties.”

PayEasy, which appears to have a small number of employees in Cyprus as well as a presence in the Philippines, has a website with a striking resemblance to Centurion’s site, and lists an identical roster of clients. None of these named clients, when contacted by the FT, could recall any dealings with Centurion or PayEasy, although most had done business with Froehlich, the Manila bus company that appears to share office space with the two payments firms.

For example, Martin Lim is the local sales manager at one purported client of Centurion and PayEasy, the Philippine distributor for Chinese bus manufacturer Higer. He told the FT he had never heard of either company and that his business did not use third-party payments companies.

“I don’t think PayEasy could accommodate our types of transactions,” which are flexible and may involve informal payment agreements, Mr Lim said from his store in north Manila. “Our sales are 90 per cent on credit terms . . . Some [customers] even start with cash payments.”

Emirates, the Dubai-based airline claimed as a client on the PayEasy and Centurion websites, said: “We have no record of PayEasy or Centurion Online Payments International as suppliers”.

Comments