Vicente del Bosque – Spain’s man of honour

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Despite having to win the coming World Cup, the only pressure Vicente del Bosque admits to on this particular morning in Madrid is the ongoing discussion with his wife Trini over which other family members will be joining them for lunch, and who has more urgent need of the family car.

Spain’s coach, 63, arrives on time for our meeting at the Eurostars Tower hotel, accompanied by Trini, his friend and confidante of more than 34 years. They have three children, one of whom, Alvaro, 24, has Down’s syndrome. While Del Bosque’s Spain was winning the country’s first ever world cup in 2010, Alvaro became an unofficial member of the squad. Afterwards Del Bosque wrote him a letter, now reproduced with his permission in a new Spanish biography. “It wasn’t Iniesta’s goal, or Iker Casillas kissing Sara, his journalist girlfriend while being interviewed by her on TV which moved me to tears. It was seeing you on TV, saying that you felt proud of your Dad, that you always wanted to help, that your heart was with him.”

WORLD CUP SPECIAL

Italy

Exclusive interview with top player Andrea Pirlo

Argentina

Can Messi ‘the Messiah’

live up to his name?

England

Why are they so bad

at penalties?

Cameroon

The team with ‘hemle’ and Samuel Eto’o on their side

Brazil

One man, a country’s hopes: superstar Neymar

Bosnia & Herzegovina

Their manager talks strategy for their debut World Cup

United States

How the US learnt to

love soccer

Colombia

Can the team affect presidential elections?

My friend Pelé

An ‘imperialist Yankee’ reminisces

How to save a penalty

Dutch goalkeeper

Michel Vorm explains

Gone are the days when Del Bosque received interviewers at his flat. But his choice of the five-star hotel for our meeting is purely for convenience. The Eurostars – near a sporting complex named in his honour – is protective of its most popular guest, or at least tries to be. During our conversation, we are interrupted four times by admirers of varying nationalities. Each is greeted with courtesy by Del Bosque, and leaves with a photograph of the world champion smiling serenely by their side.

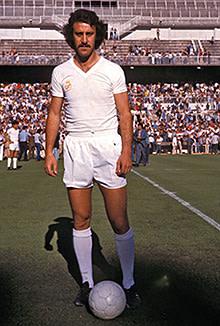

Apart from today’s venue, and a physique that has benefited belatedly from more regular exercise and a diet, I am struck by how little acclaim – including being ennobled with the hereditary title of Marques de Del Bosque – has changed him since we first struck up a friendship in 2003.

Back then, I was researching a book on the history of Real Madrid. Real is often caricatured as “Franco’s Club”. Yet Del Bosque – who spent nearly three decades at the club as player and coach – saw Real as a broad church of Spaniards of different political loyalties and regions who united behind attacking football. Del Bosque never hid his admiration for his socialist father – a railway clerk imprisoned by Franco’s forces during Spain’s civil war – nor his respect for Miguel de Unamuno, the Spanish liberal philosopher and essayist. In the 1930s Unamuno, then lecturing at the University of Salamanca, the town of Del Bosque’s birth, prophetically spoke out against the intolerance of Spain’s extreme right.

When we met, Del Bosque was struggling to contain a deep sense of sadness, if not betrayal by Real. Who could blame him? After coaching Real’s youth sides, he had led the first team to two Champions Leagues and two Spanish titles. It was the most successful period in the club’s post-Franco history. Del Bosque’s understated management was based on winning respect through personal integrity, on listening and exchanging ideas – after which he assumed responsibility for decisions. He says, “Only a bighead thinks he knows it all. One of the most difficult things is to accept when you’ve got things wrong. I am a firm believer in the culture of dialogue.”

Yet in 2003, just before David Beckham’s first season with Madrid, Del Bosque was summarily sacked by club president Florentino Perez. The overweight, balding, humble, unassuming coach wasn’t the right figurehead for the club’s commercial project based on celebrity players – or so Perez believed then.

Things didn’t turn out badly for Del Bosque. In 2008 he became Spain’s coach, inheriting from his predecessor, the late Luis Aragones, a team that had just become European champions. Already Barcelona’s players had stamped their style on Spain’s team with a one-touch passing and possession game known as tiki-taka. Del Bosque added other rising young Barça players, while also relying on more muscular, bigger men from Real such as Xabi Alonso, Sergio Ramos, and captain and keeper Iker Casillas. Del Bosque had groomed Casillas in Real’s youth teams. Now Casillas led a Spanish team built around the two rival clubs. A key axis linking Spain’s players was the friendship and professional respect between Casillas and Barcelona’s playmaker Xavi, teammates in national youth teams since they were teenagers.

Going into the World Cup of 2010, one crisis facing Del Bosque was the depressive state of his midfielder Andrés Iniesta. The player was still mourning his close friend, Espanyol captain Dani Jarque, who had died the previous summer from a heart attack aged 26. Iniesta was also scarcely recovered from injury, and had played a long and demanding season for Barcelona. He was then injured again as Spain lost its first match to Switzerland. The Spanish media attacked Del Bosque, with Aragones leading the charge.

Del Bosque didn’t panic. He talked to each player individually, reinforcing his faith in them. “In that moment of despair, it was important that we stuck together, that we found strength in unity against the forces of adversity, that we stuck to the script that had got us to the World Cup. It wasn’t the moment to change our tactics and style. So the message I conveyed was we stick to the plan.”

Iniesta was rested for the next match, and Del Bosque gave him further one-to-one counselling, listening and heartfelt reassurance. “The coach has to understand that human relations have to be above the sport, above the competition … the conversations Iniesta and I had strengthened the bond we felt with each other.”

“On the day of the final I spoke to the players. I told them to think of themselves as the romantics of football facing the most important game of their lives. I was appealing to the romanticism that I think a lot of us carry within us from childhood. However much you professionalise football, however much money is involved, the important thing is to defend the nobility of football. I told them we aren’t soldiers. We are not here to pick a fight. We are players, talented young people. We can play good football, and achieve something collectively.” In the final, Iniesta scored the winning goal, then pulled off his shirt to reveal an undershirt with the words “Dani Jarque siempre con nosotros” (“Dani Jarque, always with us”). This cathartic moment transformed Iniesta into Spain’s most popular player, and Del Bosque into the country’s most popular leader – more so than any Spanish politician, businessman or clergyman.

Del Bosque does not see great football as a substitute for good government, but is conscious that many look to him and the national team – with its successful mix of Catalans, Basques and Castilians – as an inspiring contrast to the intolerance, division and institutional failures that overshadows modern Spain. “These guys (in La Roja) are very special. They have a real sense of what it means to play as a team, to interconnect, to help each other. They are generous and altruistic,” he tells me with evident warmth.

And yet La Roja’s collective ethos has endured only thanks to Del Bosque’s skills in conflict resolution. He admits now that one of his biggest challenges came in August 2011 after Madrid and Barcelona clashed in the Spanish Super Cup, following weeks of psychological warfare by Madrid’s then coach José Mourinho. Madrid and Barça players – the backbone of La Roja – engaged in a punch-up while Mourinho poked his finger into the eye of Barça’s assistant coach, the late Tito Vilanova.

Del Bosque tells me: “It was a highly damaging situation, with the media clearly fuelling a climate of confrontation. Luckily I was not alone in realising that the images on TV did not show those involved in a good light. It simply did them no credit as sportsmen.”

The behind-the-scenes rescue operation, encouraged by Del Bosque, involved his key lieutenants Casillas and Xavi apologising to each other by phone before agreeing to broker a peace deal among their respective club colleagues. “Casillas and Xavi assumed their responsibilities to take a lead, to recognise the strength of their friendship and the importance of hanging on to what we had achieved as a national squad.”

Del Bosque also worked patiently to reconcile Barca’s Busquets and Real’s Alonso. And he worried about Barça’s Gerard Pique and Real’s Ramos. “At a training session just before Euro 2012, I took Pique and Ramos to one side and calmly told them: ‘Hey, I’m told you’re still finding it difficult to get on with each other? ‘They looked at each other, and started laughing. ‘No mister, no problem, we are ok’ they answered. So I went on: ‘Look, kids, you’re both young, you’re both good-looking, decent boys. You can achieve a lot together. So it just doesn’t make sense you not getting on. ” The two shook hands and peace reigned in La Roja.

So does he blame Mourinho for, as Pique put it at the time, nearly “destroying Spanish football”? “Let’s just say there are other coaches who seem to be guided by a mutual respect, a mutual tolerance, and there are everlasting values: education, manners. When Atletico de Madrid eliminated FC Barcelona from the Champions League this season I saw Barça fans applaud the winning team. These are gestures that I find comforting. This is better than confrontation.” (By contrast, when Atletico beat Mourinho’s Real in last year’s Kings Cup final, Mourinho was red-carded.)

Spain won Euro 2012 by beating Italy 4-0 in the final. Del Bosque considers this La Roja’s best game under his management. It was the match that gave him most personal satisfaction, because it seemed to vindicate La Roja’s unorthodox formation – often without a single striker.

…

After continuing criticism that tiki-taka had become boring and predictable, the final was a thrilling masterclass of shifting tactics. “Our three most advanced players for much of the match were midfielders – Silva, Iniesta and Fábregas – all interchanging positions. I am not saying this is the only way to play football but it worked for us that day. But I believe in players, not systems. We can also use a striker if it suits our requirements. We are flexible,“ says Del Bosque. Indeed, late in the final he introduced Chelsea’s striker Fernando Torres, who set up the third goal and scored the fourth.

More recently, La Roja’s 3-0 defeat by Brazil in last summer’s Confederation Cup final and Barça’s faltering season have raised questions about whether tiki-taka has reached the end of its usefulness.

Del Bosque believes not only that speculation about the “end of an era” is premature, but that it’s based on the false premise that Spain’s game is set in stone. In fact, at Euro 2012 and then in Spain’s unbeaten run of qualifying matches for the World Cup, he has used different formations, and mixed and matched players to try and keep La Roja fresh, dynamic and creative. He also has a huge pool of talent to draw from.

“I don’t want to be dogmatic or impose any kind of doctrine. I recognise there is not only one way of playing football. The important thing is to have players that take the ball forward that can deliver. People think they know how we play now. But we haven’t just got one way of playing. We are in an evolutionary process, “Del Bosque says.

“I would not be in the job now if I didn’t feel emotionally involved and with a strong sense of responsibility to see it through. It’s not just about going to a World Cup in Brazil, which will be a festival of football. It’s about defending our championship.”

Yet he must now manage expectations and prevent complacency. “Spanish football went from an ancestral pessimism to an excessive optimism that borders on being unsporting. We mustn’t behave like boxers who approach a title fight and say, ‘I’m going to knock you out in round two’. No, no. We have to be sportsmanlike and be realistic enough. It’s going to be very difficult to win another World Cup. If you ask what my main task is, it is to ensure that my players remain focused, and don’t lose their motivation.”

Our meeting ends as it began, with family. Del Bosque’s daughter, Gema, 21, picks him up in the family car. “Can I give you a lift anywhere?” Del Bosque asks me. Before we say goodbye, I ask about his son Alvaro. A big smile comes over his face as he shows me a photograph of Alvaro in a suit working behind a desk. “We’ve achieved what we set out to achieve, which is to find him work.” Alvaro, he says, has come to mean more to him than anything else. “I’m not very expressive of my feelings. I am not a great one for words. I am not very lyrical. I am quite a practical person. But when I think of pure love, it is what I feel for Alvaro.”

Jimmy Burns is the author of ‘La Roja: A Journey through Spanish Football’ (Simon & Schuster )

To comment on this article please post below, or email magazineletters@ft.com

Comments