Mobileye at the vanguard of the revolution in autonomous driving

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Mobileye, the Israeli automotive technology company, like other makers of breakthrough products, is reverential about its mission, using terms such as “revolutionary” and “saving lives”.

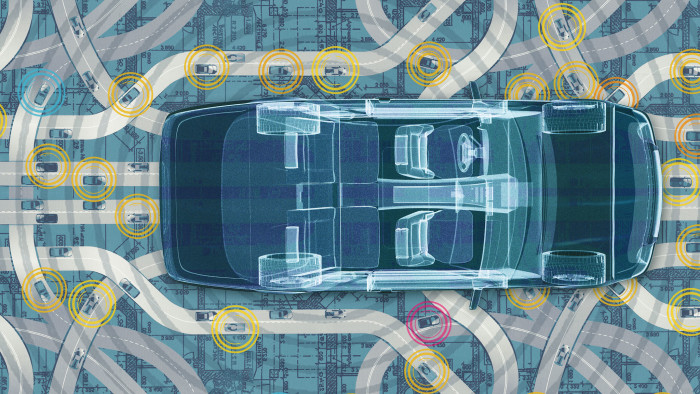

The company’s core product is a chip that uses painstakingly puzzled-out algorithms to interpret data fed via a camera mounted inside a car, to help it make split-second decisions on braking, its position in a lane or how to respond to traffic signs.

“Autonomous driving is a revolution, and we are changing the way people will drive in the future,” says Ziv Aviram, Mobileye’s chief executive, who runs the company from its headquarters in a Jerusalem business park.

Mobileye’s description of itself is not hype: the company has built an $8bn-plus company in a decade and a half by developing advanced driver assistance systems that, one by one, are taking human error — the main reason for most road accidents — out of cars.

“We are part of a success story — a common goal of saving lives,” says Ofer Maharshak, chief financial officer, describing what he says is a strong esprit de corps among Mobileye’s more than 450 employees.

The company’s products have been built into some 5.2m vehicles, introducing features such as autonomous braking to prevent a crash, or alerts when a driver is getting too close to a pedestrian or other vehicle.

These types of features were premiered in top-end cars but are quickly filtering down to the mass market and will soon become as standard a feature in new vehicles as anti-lock brakes.

Euro NCAP, the European safety standards assessment body, has made autonomous emergency braking part of the system for cars seeking its top five-star rating. The US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration is adopting similar standards, which should bring in ample business for Mobileye in years to come.

These braking systems are just one of many autonomous driving features that will allow cars to detect traffic lights, animals and pedestrians, and — very soon — to drive for long stretches on their own, giving drivers the chance to take their hands off the wheel and immerse themselves in email or other tasks.

Tesla Motors, the California-based electric car maker, has announced it will introduce an autonomous vehicle incorporating Mobileye technology this year. The Israeli company says it will supply its system to another two unnamed carmakers with self-driving cars in the production phase and another five that have cars under development.

“We are at an exciting time in the life of Mobileye,” Amnon Shashua, the company’s professorial, somewhat geeky chairman said in a recent corporate film teaser in which he previewed Mobileye’s coming technology. The film showed him in the driving seat of a car zipping down a motorway, with his hands off the wheel as he gazed sideways away from the road.

Israeli high-tech companies are world-renowned innovators in areas such as cyber security, agricultural technology and medical devices, but until now they have been thin on the ground in the car industry. But with state-of the-art software incorporating “deep learning” now a core component in car innovation, Mobileye’s time has come.

“We are just at the beginning of seeing the auto industry embrace these sensors across the board,” says Thilo Koslowski, the Silicon Valley-based automotive practice leader at Gartner, a technology consultancy. “The market for them is pretty compelling.”

Mobileye works with 23 carmakers, or about nine in 10 of the industry’s big producers. Its story about driverless cars was compelling enough for it to list its shares on New York Stock Exchange last year in the biggest-ever flotation by an Israeli concern and one of the most sought-after technology company flotations of the year.

Deutsche Bank analyst Rod Lache, in a note with a “buy” recommendation for Mobileye’s stock published in December, wrote that the advent of advanced driver assistance systems “represents one of the most compelling themes in the global auto industry”.

The company, by its own account, got its start thanks to a throwaway comment by one of its founders that prompted him to deliver on a technological dare.

Shashua, a computer vision specialist at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, was giving an in-house lecture at one of Japan’s carmakers — the company won’t say which — in 1998, when one of the attendees asked him if a car could drive aided by one camera. In the then-primordial world of driver assistance, early systems typically had two — a bulky and expensive approach that required painstaking calibration.

Yes, he said, it could: after all, a driver can drive with one eye and still see.

This stirred enough interest in the room to prompt Shashua, on his return to Israel, to take his idea to Aviram, a former retail chief executive and entrepreneur who had invested in one of the professor’s earlier ventures, a scheme to use cameras to measure the accuracy of car parts.

A few months later the men returned to Japan with a large and bulky camera-vision prototype, which sits in Mobileye’s museum — a strong enough proof of concept for them to find potential customers for its business, which they founded in 1999.

The barriers to entry for new automotive suppliers are high and the rewards often meagre. Car companies put their suppliers through difficult tendering processes, then squeeze them for the lowest possible price, in an industry where new products take years to penetrate into cars.

In Mobileye’s case, some nerve and what Israelis call chutzpah went into the company’s initial pitch to carmakers: they had to convince them their unknown company could develop not only early applications but also a suite of future products.

When the company was demonstrating to carmakers its first product — a system signalling that a car is departing from its lane — it was also showing them an early version of its vehicle detection capability; soon after came pedestrian detection. Developing three generations’ worth of products, says Aviram, was like founding three start-up companies from day one.

Cracking a system for identifying pedestrians posed special challenges. Compared with the relatively straightforward job of recognising another car, how could Mobileye’s camera pick out someone riding on a bike, for example, or the shape of two people walking together?

At one point, the company halted all other work so that its engineers could solve this single problem. They achieved the first breakthrough in two months.

Mobileye participated in its first “request for quotation”, or bid, at General Motors for a lane departure system. Its cameras went into cars made by GM, Volvo and BMW from 2007, and began to attract industry buzz.

When the time came to go public in 2014, the company took a characteristically forward-leaning approach. Aviram did his own research on life as a public company, quizzing other chief executives who had done initial public offerings.

US securities law allows for a period called “testing the waters”, when a company can test its presentation with investors before filing a prospectus. Most companies skip this, but Mobileye pursued a series of meetings that succeeded in spreading its story, so that by the time it came to list, senior portfolio managers’ interest had been piqued: the IPO was 23 times oversubscribed and Mobileye raised $1bn.

Mobileye’s share price sagged by about a third off its high early this year, as a 180-day lock-up period ended, allowing some early investors to sell stock.

The company has continued to command premium prices for its products, which it sells directly to “tier one” suppliers at the top of the automotive value chain. In addition to the chip it sells to tier ones, which account for about 80 per cent of its sales, Mobileye sells a self-contained unit incorporating both chip and camera to the aftermarket.

However, with formidable competitors such as German groups Continental and Bosch developing their own driver assistance systems, analysts say Mobileye will need to work to keep its commanding position.

“Mobileye knows it has a good product, and it can set terms and conditions accordingly,” says Ian Riches, director of the global automotive practice at Strategy Analytics, a consultancy. “The risk is that it could stumble and lose its technological lead.”

The company is, by its own account, winning in the debate about the future of autonomous driving, which it says for legal and technological reasons will come in phases, rather than a “big bang” transition directly into self-driving cars. Mobileye believes drivers will not give up complete control of their cars all at once but in stages, first in “enhanced driving” settings on highways, then in rural settings and later in cities.

Another question is how long Mobileye can remain independent, not least as the ecosystem of companies offering connected vehicles evolves. The company is not commenting on this but acknowledges the challenges. “It is a constant battle to show automakers we can do what others can’t do,” Aviram says.

Comments