Biotechs face cash crunch after stock market ‘bloodbath’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Dozens of biotech companies are running low on cash and face an uphill struggle to raise fresh funds after “tourist” investors who snapped up their shares during the pandemic abandoned the sector.

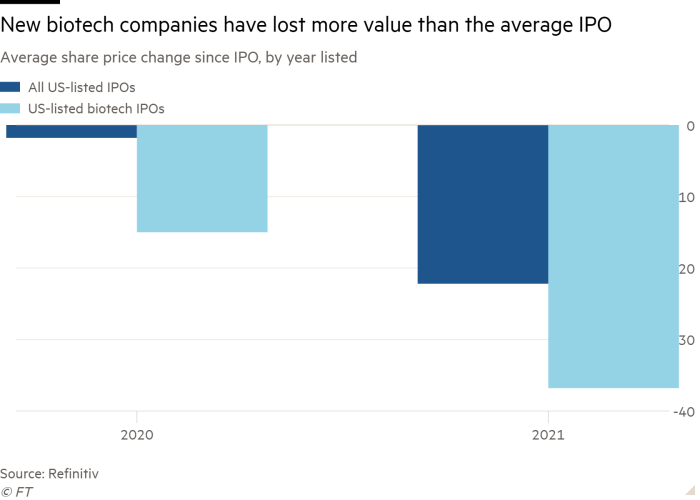

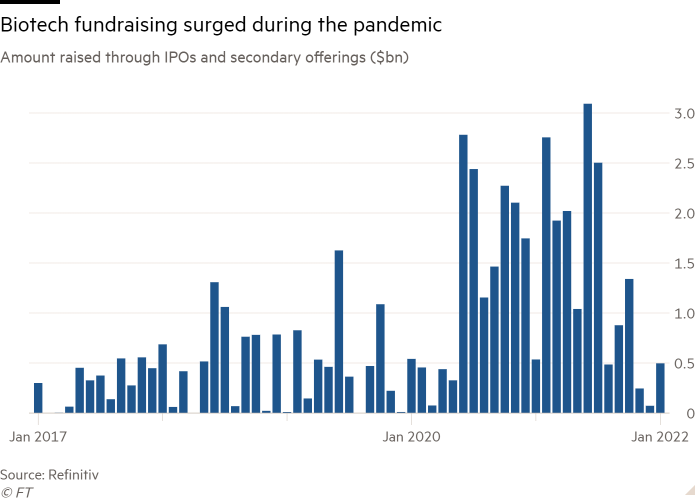

Biotech groups, most of them lossmaking, raised a record $32.7bn in initial public offerings over the past two years, according to data from Refinitiv. But 83 per cent of recently listed US biotech and pharma stocks are now trading below their IPO price.

Biotech groups that listed in 2021 are trading on average 37 per cent below their IPO price, compared with a 22 per cent fall for all newly US-listed companies.

Many such companies raised money through IPOs with the expectation that they would be able to tap investors for fresh funds in subsequent share sales as their drugs progressed through the research and development cycle.

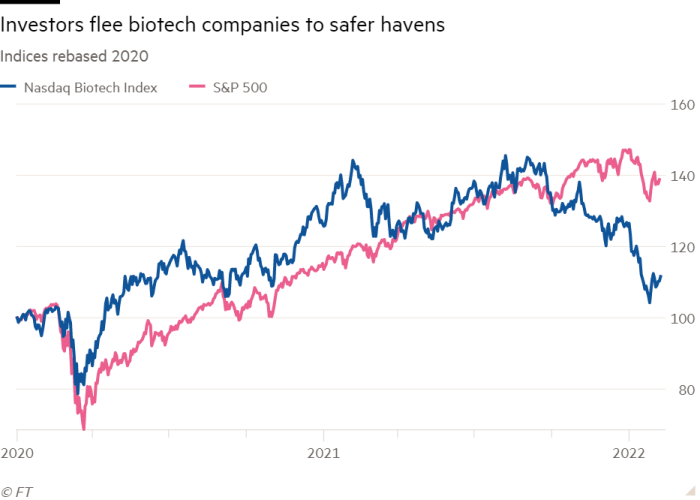

But their ability to do so has been hampered by a market rout for biotech stocks as retail investors and generalist money managers — described pejoratively as “tourists” by specialist funds — turn sour on the industry.

Geraldine O’Keeffe, a partner at healthcare investment firm LSP, said biotech shares had been hit by a “complete bloodbath across the board”. The Nasdaq Biotechnology index has fallen more than a fifth since peaking in February 2021 vs a rise of 3 per cent and 17 per cent for the Nasdaq and S&P 500, respectively.

“I think everybody is holding their breath and waiting to see if it has bottomed out and will bounce from here,” O’Keefe added. “It can’t get much lower — but we thought that every day in January and it kept going down.”

The drop has been so dramatic that the investors are bestowing some companies with a market valuation that is lower than their cash reserves. Investment bank Jefferies recently identified 31 listed biotech companies with a market capitalisation above $100mn that are trading at negative enterprise values.

The biotech sell-off has been prompted by a confluence of factors, with investors seeking safer assets as central banks prepare to raise interest rates to fight soaring inflation. Others have concluded that industry stocks became overvalued at the peak of the pandemic, when positive news about Covid-19 vaccines and treatments helped lift the sector overall.

Concerns over increased regulatory scrutiny of drug pricing and anti-competitive practices are also buffeting a sector that had relied on a steady stream of dealmaking to stay afloat.

The result is that some biotech companies are facing a cash crunch, with Jefferies identifying at least 11 that have less than one year of funds at current spending rates. The research excluded companies with a market capitalisation below $200mn or share prices below $1.

One such company is Nantkwest, also known as ImmunityBio, which cancelled a $500mn share sale in December and instead secured capital via a $470mn debt raising. Most of the funds were provided by its controlling shareholder and executive chair Patrick Soon-Shiong.

“In the current economic environment, when not just our company but the biotech sector as a whole is undervalued, it’s far more prudent for me to make this investment myself,” said Soon-Shiong, who also owns the Los Angeles Times.

Pierre Kiecolt-Wahl, co-head of equity capital markets at investment bank Bryan Garnier & Co, said that biotech had traditionally been a specialist asset class dominated by fund managers with scientific backgrounds who pored over trial data to pick stocks.

But he said that generalist funds and retail investors had increased their exposure to biotech shares, while hedge funds saw it as a “racy trade”.

“The washout in the public market is investors who maybe shouldn’t have been in the space — ‘tourists’ — going back home.”

Kiecolt-Wahl said privately held companies seeking to go public may need to take a more cautious approach, with smaller IPOs followed by a secondary offering. Already-listed companies, especially those that have experienced setbacks in the research clinic, could have to seek alternative sources of capital instead of pursuing a conventional secondary offering, he added.

Even though sector specialists blame “tourists” for the recent rout, the collapse in valuations has especially hurt biotech-focused funds. San Francisco-based Asymmetry Capital’s fund fell 10.2 per cent in the year to November 2021, according to 13F regulatory filings collated by data tracking company Whale Wisdom.

Life science-focused fund Logos Global Management fell 31.4 per cent and Boston-based Cormorant Asset Management lost 28 per cent over the same period. Logos declined to comment. Cormorant did not respond to a request for comment.

Scott Kay, founder of Asymmetry, which closed last month, said all biotech and healthcare-focused managers with a single fund with less than $2bn in assets under management would have to make difficult decisions on whether to continue operating, sell or shut down.

“We are in a new world as the Fed tightens after 12 plushy years of loose conditions,” he added.

Kay said many biotechs came to market too early and their valuations were not deserved as they did not yet have clinical data.

While the pandemic highlighted the potential for huge returns for a handful of successful companies, it made it harder to recruit volunteers for clinical studies. Hospitals were busy treating patients with Covid-19 and so diagnoses of other illnesses declined, delaying trial results and eating into company cash piles.

Investor confidence has been shaken too by disappointing news flow from biotechs, many of which do not even have drugs in human trials yet. In the 60 days before the end of 2021 Jefferies noted 23 “very negative” market-moving events and just seven “positive” announcements by biotechs.

Michael Yee, analyst at Jefferies, said poor sales of Biogen’s Alzheimer’s drug — the first treatment approved in two decades and the only one that purports to slow down the disease — had also shaken the sector.

“Companies are going to be tighter on the purse strings,” said Yee, pointing to a $500mn cost-cutting drive announced by Biogen, a large “bellwether” biotech stock.

Yee added that would mean there was “less hiring, less spending, less frothy money being thrown around”.

Some investors hope that a drop in biotech valuations will reignite M&A in a sector where dealmaking sank to its lowest level in a decade in 2021.

Big US and European pharma groups have up to $500bn of “dry powder” to spend on acquisitions as they search for promising drugs to replace declining revenues from the loss of patent protection on their existing blockbuster medicines, according to SVB Leerink.

But some bankers warn there is no guarantee that Big Pharma will turn on the dealmaking spigot and argue that low valuations are not the only factor when deciding whether to make an acquisition.

“A very high valuation may be prohibitive or may be a bottleneck for M&A happening but a very low valuation isn’t necessarily a fuelling factor for the deals to happen,” said Eric Tokat, a partner at investment bank Centerview Partners.

He said Big Pharma was unlikely to adopt a bargain-hunting approach that he described as “you can buy three for the price of one — let’s just go shopping”.

In the meantime, biotech founders and investors are asking when the market rout will end and how it will affect the sector in the longer term.

“I don’t think it is the kind of bubble we saw with the [dotcom] internet bubble, where it pops and we have a decade of reckoning,” said Brad Loncar, a biotech investor.

“The next decade is going to be defined by a global competition in sciences and biotech will be at the forefront of that,” Loncar added. “Especially after Covid, all around the world governments will prioritise investing in biotech and drug development.”

Kiecolt-Wahl said there were enough long-term buyers, including well-funded venture capitalists that saw biotech as a megatrend, to keep capital flowing into the sector.

“I don’t think we have a supply of capital problem. But the terms are obviously favouring those with the capital,” he said. “The pendulum has moved to the other side, for now.”

Comments