Companies try to cut geopolitical risk from supply chains

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In late February, 13 employees from South Korea’s Illjin Materials unfurled a company banner, raised their fists and posed for a photo in front of a truck. They were celebrating their first shipment of a new product to Samsung: copper foils that are about 50 times thinner than a strand of hair and critical to the production of computer chips.

The moment was a decade in the making, chief executive Yang Jeom-sik told local media. Samsung had first asked Illjin Materials to develop the technology to produce the ultra-thin copper to its specifications after Japan’s 2011 earthquake and tsunami. The disaster and ensuing disruption had highlighted the group’s overreliance on Japanese group Mitsui.

Illjin’s achievement is now a source of national pride: it reduces South Korea’s dependence on components and materials from Japan — a country against which Koreans hold bitter historical grievances. The development is also an example of the challenges that are reshaping supply chains worldwide, as companies everywhere try to cut their exposure to rising geopolitical tensions, just as governments try to boost domestic industries by onshoring manufacturing.

In addition, it serves as an indicator of the complexities ahead as the US and China lock horns over technology, trade and security.

Climate change, and the higher frequency of extreme weather that disrupts shipments, further complicates this picture. A 2020 report by analysts at consultancy McKinsey warned that the “economic toll caused by the most extreme events has been escalating”.

The experience of Samsung — South Korea’s most important company and one of the world’s top producers of computer chips, smartphones and home appliances — demonstrates both careful supply chain management and the dangers of being caught between competing superpowers.

The supply chains that Samsung now relies on are the result, it says, of a process that began 20 years ago when the company started to move towards a “multi-site production and multi-source procurement strategy”. That means it likes to have at least two suppliers in different locations, serving factories spread across the world, as a buffer against unforeseen events.

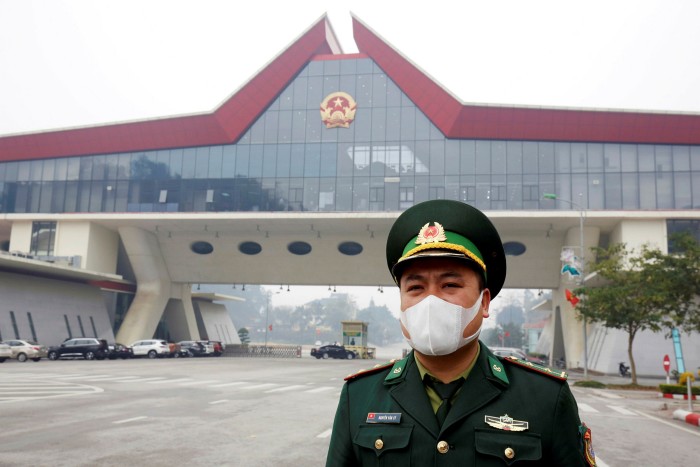

The coronavirus pandemic presented Samsung with perhaps the ultimate test of this resilience. Hitherto unimaginable problems emerged, ranging from sudden restrictions on the trucking routes between Vietnam and China, which cut off component supplies to Vietnamese factories, to an outbreak of Covid-19 infections linked to a quasi-Christian sect.

“If an issue impacted a specific supplier or production facility, we shifted to another supplier or facility in another location,” Samsung says. “This enabled us to continue operations without disruption.” The company adds that it is accelerating plans to further diversify the sources of components and increasingly turning to artificial intelligence-based forecasting and trend analysis.

“We inserted Covid-specific information, such as closed stores and traffic changes due to the pandemic, into the AI tool to predict the demands more accurately in each region,” Samsung says.

Widening divides

When it comes to many of the new problems now facing global manufacturers as the world emerges from the pandemic, however, Samsung declines to comment.

The rise of protectionism and nationalism, coupled with the widening divide between China and the west, is shaking the foundations of globalisation. Ideological disconnections and technological decoupling are increasingly hard to navigate, pulling companies such as Samsung as well as countries such as South Korea in different, possibly incompatible, directions.

Governments and companies that found their supply chains strained during the pandemic have responded with blunt calls for bringing closer to home the manufacture of anything from computer chips to vaccines. And some western governments are increasingly vocal about the risks of being dependent on China.

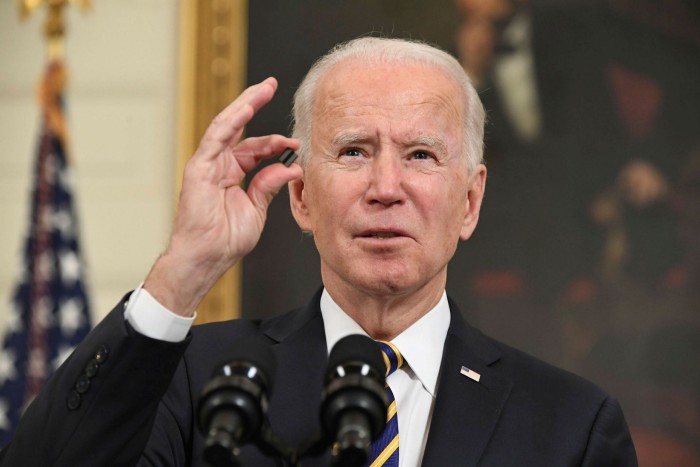

The US, in particular, “is asking a lot of its allies”, says June Park, a Seoul-based political economist and expert in trade and tech conflicts with George Washington University. After taking office, President Joe Biden announced a broad review of critical US supply chains, including computer chips, telling Americans they “shouldn’t have to rely on a foreign country, especially one that doesn’t share our interests or values”.

South Korea is being closely followed as a test of how to manage these new challenges. While Seoul continues to maintain close defence and security ties with the US, Park says the government and South Korean companies are also pursuing a tenuous “dual track” on economic issues. They are essentially trying to retain market access to both China and the US.

As for Samsung, a discreet effort to de-risk its supply chain has seen it withdraw a huge swath of its smartphone manufacturing and assembly from China over the past decade. It has shifted instead to Vietnam, where it also benefits from cheaper labour and the stability of another single-party authoritarian government. Samsung’s relatively early move is now being followed by other multinationals

Nevertheless, Samsung continues to invest heavily in its China-based manufacturing of computer chips. This ensures continued access to fast-growing tech giants for its biggest revenue driver: memory chips. It also wins political favour in Beijing, as president Xi Jinping has made reducing China’s reliance on foreign-produced chips a core policy.

Park adds: “The [Chinese] market is so huge, the argument that it is a ‘Faustian bargain’ . . . it just doesn't sell in Korea.”

Comments